The lack of attainable housing in the United States continues to be a widespread and urgent concern. In early February 2025, hundreds of stakeholders and real estate professionals gathered at DeSales University for a meeting sponsored by ULI Philadelphia and Lehigh Valley Planning Commission and supported by ULI’s Terwilliger Center for Housing and Lehigh County Commissioners. “Housing Supply and Attainability Strategy in the Lehigh Valley,” the first installment of a three-part Technical Assistance workshop, aimed to open the conversation and further shape the technical assistance work to follow.

With a goal of ultimately helping the planning commission develop a housing strategy that can reduce current housing shortages and increase attainability of nonsubsidized housing across all income levels, the session brought together local government officials, school district administrators, county officials, state local government, federal representatives, housing developers, real estate professionals, financial institutions, planners, engineers, architects, and employers.

“Housing is at the core of our communities,” said Becky Bradley, AICP, executive director of the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission, in her introductory remarks. “It’s where we connect our lives, build our careers, and invest in our futures. But as we all know, the Lehigh Valley, like many regions across the country, is facing a significant challenge. Our population has steadily grown by about 4,000 residents each year. The demand for housing has outpaced supply, leading to rising costs, increasing competition, and a growing gap between household incomes and housing price points.”

The region’s ability to attract a strong workforce and retain young residents and families depends on the commission’s ability to find solutions for this issue, she said. Additionally, any truly sustainable solutions must recognize the interdependence of transportation, infrastructure, land use, land development, zoning, regulatory guidance, farmland preservation, and natural resource conservation.

Data to inform solutions

The morning’s first speaker, the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission’s Chief Community and Regional Planner Jill Seitz, talked about the research behind the commission’s strategic goals: “The Lehigh Valley has a strong history of addressing housing needs, thanks to the programs and services provided by Lehigh and Northampton counties, our local governments, and our numerous community organizations, whether it’s providing shelter for those [people] experiencing homelessness or constructing housing for low-income individuals and households. The Lehigh Valley Housing Supply and Attainability Strategy is supplemental to these services by coming at housing from a different angle, focusing on increasing the supply of nonsubsidized for-sale and for-rent housing at a range of income levels.”

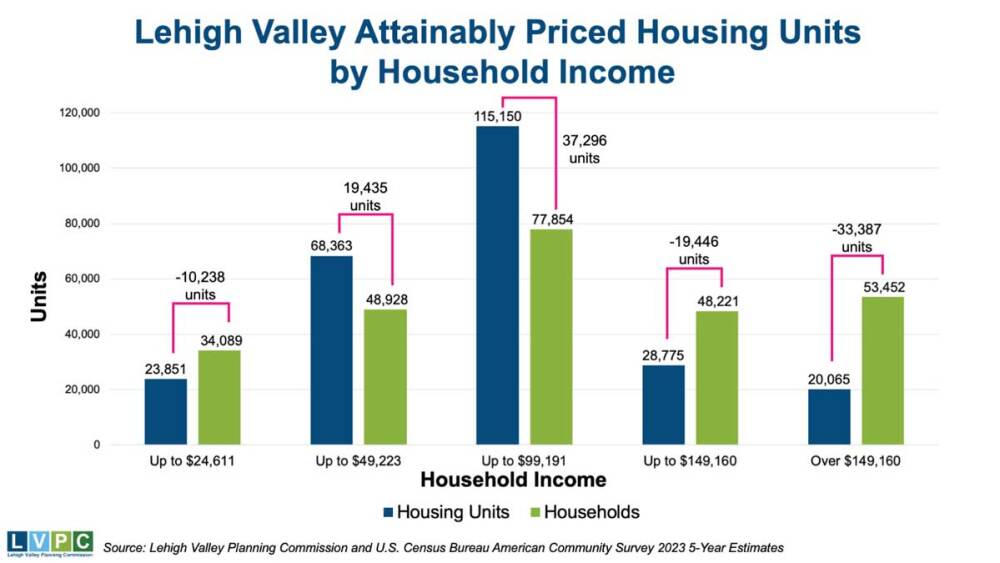

Seitz defined “attainability” as including not only the right quantity of housing units but also a diversity of units across housing types and price points. In the Lehigh Valley, the existing mismatch of units means that higher-end households are pressured to buy or rent down while lower-income home-seekers must buy or rent up. For instance, whereas the planning commission’s data shows a 57,000-unit surplus of homes for people with incomes between $25,000 and $100,000, it also shows a 53,000-unit deficit for people with incomes above $100,000, and a 10,000-unit deficit for people making less than $25,000.

The 9,000-unit shortage is compounded by a lack of new housing development in the region. With the Lehigh Valley growing by nearly 4,000 people a year, some 54,000 housing units will be needed regionwide by 2050, but numerous factors are stymying development. They include developer backlog, high interest rates, inflation, materials and labor shortages, overburdened school districts, lack of infrastructure, restrictive land use regulations, and community resistance. Housing prices have outpaced income growth here, as elsewhere, and if the rise in housing costs continues, the average home will cost seven times the median salary by 2050—an unsustainable outcome.

The urgency to address these issues is keenly felt, Seitz said. “The universal nature of housing means it’s not just about shelter. It’s about economic stability, workforce retention, and community sustainability. If people can’t afford to live where they work, businesses struggle to attract and retain employees. Increased commuting distances and train transportation systems harm the environment. Additionally, municipalities must rely on stable housing markets for their tax revenues and efficient service delivery. Without action, the children and grandchildren of the Lehigh Valley residents will be priced out of these communities where they grew up.”

Tracking housing availability

Seitz and the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission have developed a website that Seitz calls “a living platform” dedicated to the regional housing problem. An online story map allows viewers to track ongoing progress, map which kind of housing is needed where, and compare how prices relate to income levels.

Through color coding, viewers can identify where housing is attainable, affordable, and diverse, or some other mix of these qualities. Seitz demonstrated on the tool, for instance, that boroughs and cities in the Valley have the most diverse types of housing, but more multigenerational housing units are needed to meet current demand. Meanwhile, the Lehigh Valley Housing Dashboard can be used to monitor current housing stock and project future needs—an ideal tool for developing regulation, planning for schools, developers, and real estate agents.

National models

In her keynote session, Deborah Myerson, AICP, senior research and policy fellow for the Terwilliger Center for Housing, provided national context to the housing struggles in the Lehigh Valley. Among the core challenges is that the cost of homeownership and rents are at record highs, and smaller metro areas such as the Lehigh Valley have shown the greatest growth since 2020. Drawing from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies The State of the Nation’s Housing 2024 report, Myerson offered numerous solutions for encouraging market-rate development based on models created around the country.

“Often the regulatory environment encourages a certain type of housing, and that creates a mismatch between the demand and what can readily be built,” Myerson said.

Some solutions include reforming zoning and other regulations to spur housing development. One case study she shared described how Montgomery County, Maryland, supported the creation of mixed-income neighborhoods by legalizing the development of townhouses, courtyard apartments, and multigenerational housing in its attainable housing strategy.

Similarly, Raleigh, North Carolina’s 2021 Missing Middle Zoning Reforms eliminated single-family zoning restrictions, enabling the development of duplexes, townhomes, and cottage courts. In Arlington County, Virginia, a combination of financial support; reduced restrictions such as lot sizes, setbacks, and parking requirements; and streamlined approvals have made building more multigenerational housing faster, easier, and cheaper.

In Worcester, Massachusetts, a mix of financial and technical support promotes rehabilitating and maintaining older housing stock. In Portland, Oregon, temporary waivers and permanent updates to zoning codes allow for the development of more housing. Myerson suggested some other best practices: leveraging state and local funding incentives, increasing access to land, forging public/private partnerships, tax financing, and considering all forms of infill housing. She cited, as an example, Wendell Falls—a new master-planned community in Wendell, North Carolina—which is successfully combining market rate and affordable housing.

Insights and opportunities

In the afternoon session, a panel of experts, including Seitz; Myerson; Thomas Comitta, president of Thomas Comitta Associates Inc.; Jason Duckworth, president of Arcadia Land Company; Stephen Murphy, executive vice president and chief operations officer of Penn Community Bank; and Justin R. Porembo, chief executive officer of Greater Lehigh Valley REALTORS®, convened to share their expertise on current market conditions in the region.

When asked about buyer and renter demand, Porembo confirmed that the Lehigh Valley is still a sellers’ market, where the lack of inventory continues to force buyers to buy down, thus creating pressure on affordable and workforce units.

“We really see the $200,000 to $300,000 price range as the sweet spot, averaging about 17 days on market,” Porembo said. “Everything under $100,000 is staying on the market for the longest—41 days or longer—and [it] may be that these properties need remediation and renovation.”

One concern for many buyers, Murphy said, is that even if they secure financing and take advantage of bank incentives such as lower closing costs, they are often competing with cash payments from more affluent homeowners or investors. What’s more, higher interest rates are deterring people from moving out of their current homes, even if they are ready to downsize or upgrade. At the same time, in a high-interest environment, with higher home prices and static wages, the constraints of debt-to-loan ratios are making buyers less eligible for financing than at any previous time.

On the developer side, finding solutions for this current state of market “lock-in” is equally challenging, Duckworth said. “We have acute demand. We are often asked why we can’t provide attainable housing. The answer is that land is very expensive, the price of materials and labor are high. Our margins are very slim.”

To address that problem, Murphy suggested that banks need to expand financing options. “We have plenty of consumer options, but there’s got to be more creativity in terms of making financing more broadly available to builders and developers of all sizes.”

Policy and regulatory solutions will be key, said Comitta, a town planner, landscape architect, and consultant who has worked with dozens of Pennsylvania townships. “In Charlestown Township, Chester County, we created an accessory dwelling unit ordinance amendment, which helps us expand housing types and create more diversity. We can also look at opportunities for revitalization and redevelopment. We can look at the transfer of development rights. What I’m seeing is a matrix where the different opportunities are merged with place types. So, some of the solutions would be . . . unique to cities, others for boroughs, and so on.”

Cross-sector collaboration, streamlining the project timeline, and building smaller can reduce costs for developers. Duckworth suggested that townships and municipalities create zoning with provisions for smaller, more attainable homes to make more “missing middle” housing attractive to developers. Finally, the panel agreed that better communication is needed, particularly on the part of developers conducting community engagement and building consensus for new projects.

As the day came to a close, ULI Philadelphia invited participants to share feedback on three questions: What types of housing are most needed? What is the greatest opportunity and what is the greatest threat to increasing housing supply? What role do you see playing in the work to address these challenges? The responses will be used to shape the follow-up event, a two-day Technical Assistance Panel, to be held March 27–28, as well as a third session to share findings and recommendations.