It’s no secret that construction starts are down in the current market, where higher interest rates are making new projects tough to pencil out. For some developers, though, the bigger problem these days is sourcing equity versus debt.

Developers are having to bring more equity to the table in a market where lenders, across the board, have pulled back on leverage. “The challenge, and maybe the reason that construction financing is down, is that institutional private equity has been sitting on the sidelines, for the most part, for the last 15 to 18 months,” says George Maravilla, a partner at Scottsdale, Arizona–based Tower Capital. If developers don’t have the equity, they don’t have a path to secure their debt financing, he adds.

“Deals are still getting done on the construction lending side. It’s the equity side that we’re having more trouble with, because these investment companies are saying, ‘Let’s hold [back] until we see what the Federal Reserve will do with interest rates’ before they make a move,” says Vicky Lee, senior vice president, development at Focus, a development and construction firm based in Chicago. In addition, because there haven’t been many investment sales that are not distressed, it’s difficult to determine exit values and cap rates, which makes it difficult for investors to underwrite new construction projects, she notes.

Focus has several projects in the pipeline, including one multifamily project in the Fulton Market submarket of Chicago that is shovel-ready. In that case, the firm is facing the added challenge of courting investors who appear to be wary of the Chicago market in general. Lee attributes that condition to some of the negative headlines related to such issues as property taxes and crime, which might be untrue or apply only to specific submarkets.

The firm also has a handful of apartment projects in South Florida that are in the early construction drawings stage, such as the 517-unit 128 Southwest 7th project in Miami. And even though that market remains hot, investors are more cautious now than they were in the past. “[Although] we are testing the waters on our Florida projects, a lot of equity partners and new construction lenders are not willing to step in early,” Lee says. That wariness represents a change from a couple of years ago, when Focus could market an early-stage development to investors who were eager to get involved during pre-development. Now the firm is finding that before investors commit capital, they want construction drawings done; the guaranteed maximum price in place; and even some of the pre-development steps, such as infrastructure and utilities, complete.

Down but not out

In 2023, construction financing dropped 38 percent, to $47.1 billion across apartment, office, retail, industrial, hotel, and seniors housing and care properties, according to MSCI Real Capital Analytics. Although higher capital costs are a big pain point, they aren’t the only reason for the decline. Developers also are tapping the brakes because of softening in some sectors due to an imbalance in supply and demand, especially in industrial and multifamily.

Debt financing for construction projects has by no means dried up. Capital is still available from a variety of sources, including banks, debt funds, life insurance companies, and private money lenders. For example, Tower Capital has a client that is about to sign a term sheet for a construction loan on a build-to-rent project in the Midwest. That deal went out to 40 groups, and Tower received term sheets from eight interested lenders.

Last year, Tower Capital arranged more than $500 million in construction financing for borrowers that were building commercial, multifamily, and build-to-rent projects. “We [use] all available capital sources out there, based on whatever the client’s goals and objectives are,” says Kyle B. McDonough, cofounder and managing partner of Tower Capital. If a client wants a low rate on lower-leverage construction financing, the best source is likely to be a bank, whereas higher-leverage non-recourse financing is more in line with a debt fund execution.

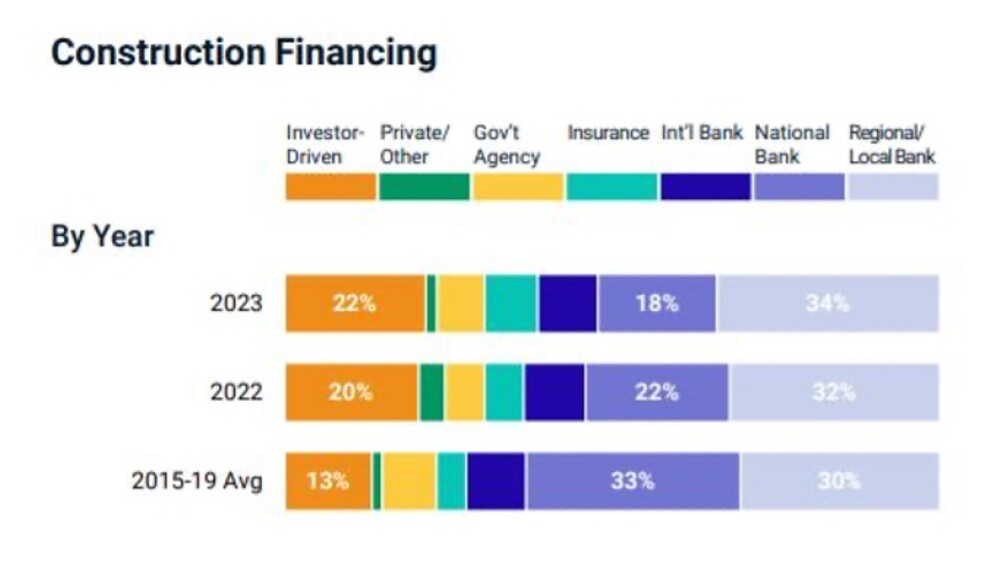

Despite some pullback from banks, they continue to represent the dominant source of construction financing. According to MSCI Real Assets, banks represented 61 percent of total construction lending in 2023. Notably, regional banks were the most active, originating 34 percent of construction loans, while investor-driven lenders represented 22 percent of the volume.

Historically, life companies have always had a bucket for construction financing, with a specific focus on doing construction-to-perm loans. “It’s not a huge bucket; it’s usually limited to a certain dollar figure, but we are still seeing the life companies doing construction loans,” says Zalmi Klyne, managing director, debt and equity at Northmarq. Although most construction lenders are offering floating-rate debt, life companies offer 7-year or 10-year fixed-rate loans that carry through the construction period and then roll into a permanent loan.

Coming to grips with new terms

Borrowers are adapting to a market where lenders are in the driver’s seat and it’s a very different environment when it comes to rates, leverage, terms, and underwriting. Historically, lenders have used market rates to underwrite their exit, and today’s higher interest rates are changing loan metrics.

For example, Northmarq closed a loan 12 months ago where the lender was using a 6 percent exit interest rate and a 1.15x debt service coverage ratio. Today, lenders are using a 7 percent exit rate and a 1.25x DSCR. In addition, guidelines where they would go up to 75 percent loan-to-cost (LTC) has pulled back to a maximum of 65 percent LTC, with some bank lenders that are staying conservative with leverage at 45 to 50 percent. “It’s a trifecta. Rates are higher. Banks are being more conservative using a higher exit rate in underwriting to size the loan, and a higher debt service coverage ratio. On top of that, banks are more selective, and in some cases, only lending to existing customers,” says Klyne.

Pricing varies depending on leverage, with low-leverage lenders that are willing to price deals tighter. For example, a loan at 50 to 55 percent LTC with some recourse and a good relationship with the bank is going to be priced at around 200 to 250 basis points over SOFR. In comparison, loans where leverage is at 70 to 75 percent are likely to price at 450 to 500+ over SOFR.

To further illustrate how the construction financing market has changed, Tower Capital did a construction loan for a build-to-rent project in Texas that closed in February 2022. That loan was 80 percent LTC at SOFR+ 535, which put the rate at 5.4 percent. The firm recently arranged financing for a similar deal in the same Texas market that closed in November. Leverage was lower at 72 percent and the spread on SOFR was the same at 535, but given the increase in interest rates, the rate on the loan was 10.7 percent. That just shows how dramatically the construction financing market has changed in the past two years, notes Maravilla.

In addition, lenders are focusing more heavily on the experience of the sponsorship group. “That is almost more important than the equity and the source of the equity,” says Maravilla. Is this deal number one, or is this deal number 30? If it’s deal number 30, that lender is going to feel more comfortable providing capital, because even if things don’t go according to plan, hopefully the sponsor has the experience to make things work, he adds.

Slower pace continues

Although the outlook for construction financing is going to depend on what action the Fed decides to take on interest rates this year, many are bracing for a slower pace of activity.

Even developers that have their own equity are looking at the high costs and realizing they can’t hit their internal return metrics because the interest rates are just too high. However, construction could start picking up again in the first or second quarter of 2025.

“What we tell developers is that if you have a deal that makes sense, there is money out there. It might be a little more expensive than you want, and it might be a little less loan dollars, but they can get it done,” says Klyne. And those projects that do have the ability to move forward are going to benefit from the slowing pipeline of deliveries ahead in 2025, 2026, and 2027. “They’re going to have very interesting opportunities in markets where they’re building because there’s not going to be a lot of new supply to compete with,” he adds.