When Bud Liebler, a former Chrysler executive, purchased the historic Whitney Mansion in Detroit in 2007, the 22,000-square-foot (2,044 sq m) granite structure—built as a lumber baron’s residence in 1894 and converted into a restaurant in the 1980s—had decorative stone carvings, a round tower with a conical roof, 20 fireplaces, and several stained-glass Tiffany windows. But the heating and cooling systems had aged badly, and cold air leaked through the structure’s 214 windows. “We were going from crisis to crisis—in the wintertime, we had to close off certain rooms, and in the summertime, we had to bring in portable air conditioners,” Liebler says. At times, the restaurant had to reimburse guests unhappy about dining in a freezing-cold dining room. The annual utility bill totaled $115,000.

When Liebler learned about the state’s Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) financing option, he jumped at the chance to fix the mansion’s energy inefficiencies. C-PACE enables property owners to borrow money from a private lender to retrofit energy systems in existing buildings or upgrade them in new construction. The money is repaid via fixed payments over a period of 20 to 30 years through an assessment on the owner’s property tax bill.

In 2017, Liebler’s company, New Whitney Real Estate, obtained an $863,000 C-PACE loan from Petros PACE Finance of Austin, Texas. The money allowed Liebler to replace the mansion’s 30-year-old heat pump system with a new heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning system; upgrade the electrical system; replace the leaky storm windows; and swap out more than 1,800 incandescent light bulbs for light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Mansoor Ghori, chief executive officer of Petros PACE Finance, says that other kinds of financing available for upgrading historic buildings’ energy performance often do not pencil out.

“With historic properties, typically a lot of work needs to be done, because they’re so old,” Ghori says. “If you go to a bank, the payback period is three years, five years if you’re lucky. You’re always underwater.” With C-PACE, the savings from energy efficiency measures are usually greater than the additional property tax assessment payments, in part because of the longer 20 to 30 year payback.

As awareness of C-PACE increases, it increases the odds that owners will adapt historic buildings rather than raze them, says Michele Pitale, managing director of retrofits for Counterpointe Sustainable Real Estate in Greenwich, Connecticut. “With most older properties, it’s easier and cheaper to tear them down,” she points out. “Much of the time, the architecture is tremendous. It’s the inner workings, the elevators, the energy systems, that are very capital intensive. C-PACE is a way to incentivize owners to preserve these buildings in a way that meets their internal rate of return and maintains the building.”

Counterpointe provided $1.02 million in C-PACE financing for the Belt Line Center in Detroit, designed by local architect Albert Kahn and completed in 1915 for the Standard Motor Truck Company. The owner used the loan to install a green roof and rain garden, improving energy efficiency and helping to detain and filter stormwater runoff. Designed by Inhabitect, LLC of Traverse City, Michigan and ECT, Environmental Consulting & Technology of Detroit, the project also relied on a $50,000 grant from the Detroit Water and Sewage Department. “The Belt Line Center is a nice project because it’s a plain brick building, a former auto manufacturing plant, close to the Detroit River,” Pitale says. “The owner could have knocked it down, especially given that Detroit is redeveloping the waterfront, but he’s turning it into an artisan community with low rents, right on one of the new greenways that Detroit is putting in. It’s an example of Detroit’s resurgence.”

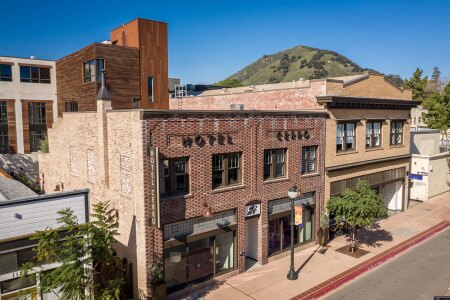

WestPac, an investment, development, and management firm based in Santa Barbara, California, obtained an $11 million C-PACE loan from Petros PACE Finance to upgrade the seismic system at the Hotel Cerro, an early 20th-century building in downtown San Luis Obispo, as part of a larger rehabilitation that added event rooms, a distillery, a rooftop pool and bar, and a rooftop garden. The hotel reopened in 2019. (Hotel Cerro)

Beyond Financing Energy Efficiency

Thirty-eight states have passed legislation authorizing Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) financing to date, according to the nonprofit organization PACE Nation. Some states also allow C-PACE to be used for purposes beyond energy efficiency. Florida has allowed wind resistance improvements to qualify for C-PACE financing since 2012, and California and Washington both permit seismic upgrades to qualify.

In San Francisco, municipal officials used C-PACE to help owners of older multifamily buildings meet seismic strengthening requirements. In 2013, the city amended its building code to establish the Mandatory Seismic Retrofit Program, requiring owners of pre-1978 wood-framed buildings of three or more stories and five or more dwelling units to seismically strengthen their properties. A number of the city’s famous “Painted Ladies,” colorfully painted Victorian and Edwardian structures, fell into this category. In 2015, the city set up the Soft Story Retrofit Loan Program, naming Counterpointe as financier for the PACE loans. “These are $100,000 to $200,000 retrofits,” Pitale says. “A lot of the owners panicked, because these were family-owned buildings, where the $150,000-a-year rent that they were receiving was helping to pay for a cousin’s college education. So, we have financed almost $65 million in seismic retrofits in California, most of it in $100,000 and $200,000 increments for these multifamily buildings. I think that has been a tremendous success for C-PACE, taking the burden off the families who own them.”

More states are considering introducing legislation to authorizing C-PACE, and a number that already authorize it are amending legislation to expand it. “The current expansions are to allow longer-term financing or to include resiliency and indoor air quality,” Pitale says. This year, Alaska enabled C-PACE improvements to air quality and resiliency measures. The state of Washington has even changed the name of its C-PACE program to “C-PACER,” with the “R” standing for resiliency. “Every state puts their own flavor on PACE, depending on the local needs,” Pitale says. “Washington, D.C.,’s program allows wildlife pathways to be financed. Utah wants to preserve open space, so they allow parking garages to be financed.”

Above and below: Counterpointe provided $1.02 million in C-PACE financing for the installation of a green roof and rain garden at the Belt Line Center in Detroit, originally designed by noted local architect Albert Kahn and completed in 1915 for the Standard Motor Truck Company. (Courtesy of Inhabitect, LLC)

The Pace of C-PACE Is Increasing

C-PACE has been around since 2008, Ghori notes, but the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated adoption. “Before, it was an educational process, trying to get developers and property owners to understand what C-PACE is, how it can be used to do projects like this, and where it fits into the capital stack,” he says. “But when COVID hit and the market seized up, there was no longer access to the various kinds of capital that property owners or developers were used to getting for these kinds of projects. They started looking around for new capital sources, and C-PACE was there. Our business tripled during COVID. And industrywide, I would say that $2 billion worth of PACE loans will be done this year.”

The size of PACE loans has also been increasing in recent years. “The Whitney deal was about $860,000,” Ghori says. “Now we’re looking at deals that are north of $100 million, for just the PACE part. We closed on an $89 million loan for 111 Wall Street in New York City last June. That opened the eyes of a lot of the institutional players and landowners, showing they could actually use these for larger projects.”

According to data from PACE Nation, cumulative C-PACE investment since its inception has grown from $868 million in 2018 to $3.4 billion in 2021. “I still believe that C-PACE is in its infancy in terms of where it will be eventually,” says Kevin Augustyn, vice president in the North American CMBS, Global Structured Finance group at DBRS Morningstar in Chicago. “There has been a growing need for funding to increase energy efficiency, resiliency, and seismic safety. C-PACE, because of the way it’s structured, is tailor made for these kinds of things.”

As more municipalities pass legislation regulating the built environment in these areas, C-PACE fills an important financial gap. “The poster child for that is Local Law 97 in New York,” Augustyn says. It requires building owners to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2024, with substantial fines for noncompliance. “C-PACE is also catching the attention of a lot more institutional players, who are now looking to provide C-PACE financing,” Augustyn adds. “Up until now, that has been the purview of C-PACE capital providers who match up investors who want to buy C-PACE bonds and notes with people who need the funds for the renovation projects.”

Awareness of C-PACE’s advantages is increasing among developers, according to Augustyn. “It’s a reasonably priced part of the capital stack and can be used as a substitute for expensive debt, whether mezzanine debt or even equity,” he says. It is also being used more and more for either ground up construction projects or significant rehab projects. “When it first started, CPACE was used to retrofit buildings, upgrade HVAC systems, upgrade lighting, provide more insulation, and provide additional seismic support, but now it’s being used for much larger-scale projects, both in terms of size and complexity,” Augustyn says.

Considerations for Historic Property Owners Using PACE

One consideration for all property owners looking to tap into C-PACE financing is that, for an amount that might be in arrears, or, for payments that might fall into arrears, the C-PACE lender steps in front of other lenders who already have a secured interest in the property. “Most state programs require that you receive written consent from the first mortgage lender, because you’re going to put them in a further back position,” Augustyn says. “Also, if you are using historic tax credits, either state or federal, you typically accomplish that by using a bridge loan to finance your project. When the project is complete, the State Historic Preservation Officer or the National Park Service reviews the final outcome and then issues credit, which then repays the bridge loan. So you need to get written consent from that tax credit bridge lender as well, because you’re pushing them further back into the capital stack.”

In general, C-PACE works well with other financing mechanisms, Augustyn says. “A very common kind of project that we’re asked to rate is an older building or hotel that’s being refurbished, for example, into a new or an upgraded hotel. In those type of transactions, C-PACE plays a critical role, but these are usually economic development projects too. So it’s not uncommon for us to see a transaction that has a first mortgage, some type of a tax credit—either historic tax credits or new market tax credit—and perhaps some funding from the federal EB-5 visa program. All of these economic development financial incentives, properly structured, can play very well with C-PACE.”

For now, energy efficiency upgrades continue to make up the majority of C-PACE investments—55 percent, according to PACE Nation. For Bud Liebler, C-PACE was essential in making the Whitney a comfortable, welcoming environment. With the retrofits completed, his days of having to close off certain dining rooms are over. “Our heating costs went down substantially, and our cooling costs are lower in the summer,” he says. “We actually have heat when we want it and cooling when we want it. When you close the windows, they stay closed, and the wind doesn’t blow the soup out of your bowl.”