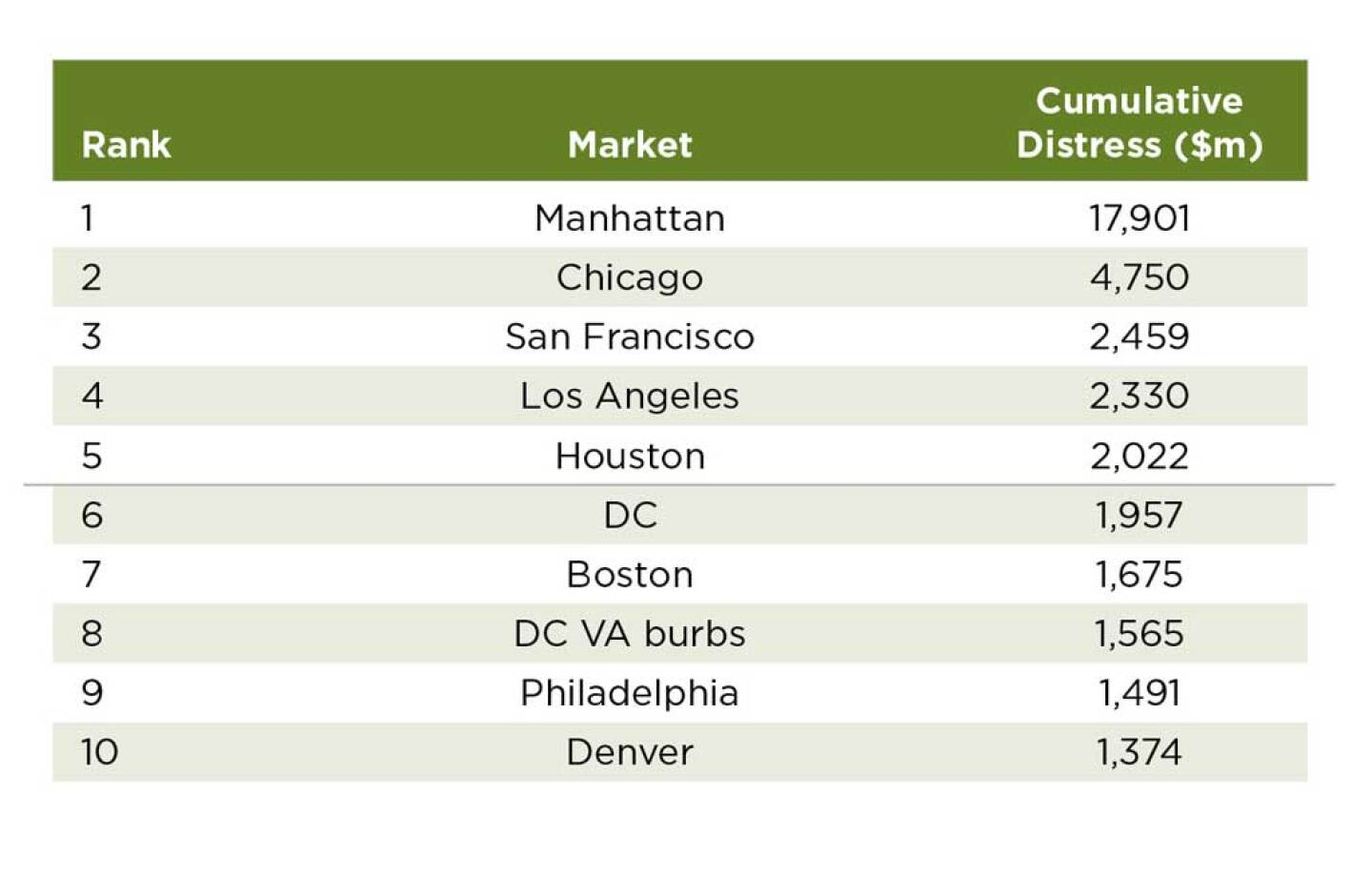

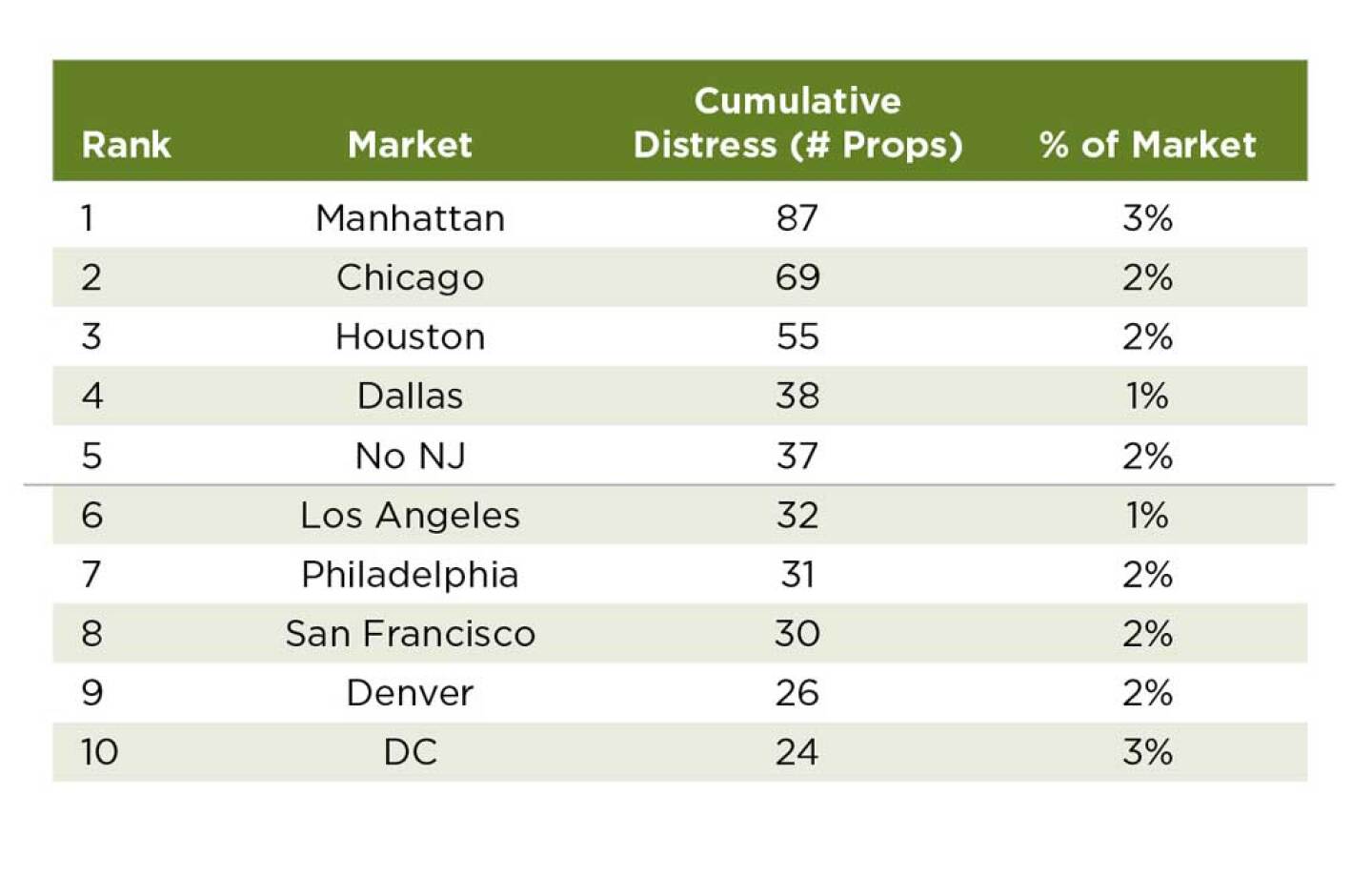

Despite improving return-to-office numbers, the office sector still battles numerous challenges that are resulting in higher loan defaults. According to MSCI Real Assets, office leads the charge on rising distress levels, which have not been seen in more than a decade. Office accounts for nearly half of outstanding distress: $51.6 billion in outstanding distress at the end of fourth quarter 2024, and another $74.7 billion in office properties identified as at risk for “potential” distress.

Most Distressed U.S. Office Markets | (Data Through 2024)

Urban Land: Office has traditionally been the core foundation for downtowns and central business districts in major metros. What challenges does office distress pose for the health of urban centers, and what opportunities do deeply discounted office assets present to make stronger cities for the future?

Glenn R. Mueller, PhD, professor emeritus, Franklin L. Burns School of Real Estate & Construction Management, and academic director, Bailey Program for Family Enterprise at the University of Denver

The post-Covid shift to work at home caused the largest disruption in the history of office real estate. People working in downtowns were the major demand driver for all other urban property types, including retail, apartment, hotel, and even industrial. The decline of the major demand driver has hurt all the property types. The future of office continues to be a “jump ball,” with much of work from home being more attractive to employees. Many businesses are trying to get employees back to the office—but allowing for one or more days as work from home. The decreased amount of space needed is currently estimated at . . . 10 percent to 40 percent.

Unfortunately, urban offices take many years to plan and build—five to eight years in most cities—so, new supply is still coming online at just the wrong time. However, new class A–plus real estate is in the highest demand as employers want attractive, well-located space to lure employees back and also impress clients. This makes class B and C office properties the big losers. Many are hoping that conversion to other property types might help reduce the office oversupply, but estimates are that only 20 percent to 30 percent of existing urban office buildings are physically and financially feasible for conversion to office.

One bright spot is that the millennial generation enjoys living downtown—and thus prefer to work there also—helping to improve demand. Also, the fast-growing AI industry is in need of lots of office space, with San Francisco being the largest beneficiary of that demand currently.

Jim Costello, chief economist, MSCI real assets research

There has been a lot of gloom and doom around office—offices are going to be empty; no one is going to go back to offices; and cities are going to die because they can’t get tax revenue from that. That kind of thinking is linear. One thing happens, and it expands at a linear pace forever, and all is either fantastic or gloomy. But that’s not the way the real world works, because you have countervailing influences.

Some owners with distressed office loans are going to say, “I just can’t make this work anymore.” They’ll have a discussion with their lender, and some deal will be reached, and the property will end up in somebody else’s hands at a much lower basis. That lower basis is a countervailing influence that can make distressed office assets usable as offices again. If you’re taking on a distressed office asset at half the cost that somebody paid at the peak of the cycle, suddenly you can do other things. If I buy a building at half the price of the building across the street, I can rent it out at a much lower price and still make money. It can also incentivize people to do other things with their office space, because it will be cheaper to amenitize the space or devote more space just for meetings, gatherings, or a lounge-like atmosphere.

Some people are looking at office opportunistically, thinking they can buy assets on the cheap, but it’s different distress than in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, because that calamity involved assets that had a capital stack that was not efficient and too highly leveraged. This time, it’s more about fundamental distress and a changing nature of tenant demand for the asset class. So, it’s going to hit differently, and it won’t have the same optimistic angle for folks who are trying to play the same strategy as last time.

Jessica Morin, director, U.S. office research, CBRE

The Covid pandemic disrupted 30 years of urban growth as many urban residents moved to the suburbs and remote work became a necessity. Five years later, most office-using employees are working hybrid schedules, visiting the office two to three days per week. Still, this shift has led to record-high office vacancies in downtown areas, which are unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels anytime soon. Higher interest rates and inflation are an additional challenge to demand.

Not all segments of the office market are experiencing the same trends. Prime buildings in vibrant, mixed-use districts are seeing healthy demand and rent increases, while nonprime buildings in office-centric locations are struggling. Declining values for nonprime downtown office buildings are affecting municipal budgets, as tax revenue from these properties is a significant source of income for many cities. Cities must quickly determine the best uses for buildings and land in their downtowns to adapt to changing work patterns and mitigate risks to municipal revenues.

Deeply discounted office buildings present opportunities for cities to reinvent and revitalize their urban cores. Converting or demolishing older, underutilized offices to new and better uses can help attract more residents, visitors, and businesses, driving vibrancy and tax revenue. Even though conversion activity is rising, it’s not yet making a significant impact on the overall office market, because these projects are complex and expensive. With targeted efforts, these projects can drive change in their neighborhoods. Public and private stakeholders must work together, leveraging their experiences and resources to shape and transform cities effectively.

William Maher, director, strategy & research, RCLCO Fund Advisors

Distressed office assets are a problem in almost all central business districts, across the country. Trepp reports that over 10 percent of office CMBS loans are delinquent, up from 6 percent a year ago. According to NCREIF, CBD office buildings have produced an average annual appreciation return of -16 percent over the past three years, and market values of NCREIF properties are down 45 percent over the past five years, including net sales. Assessed values may take a while to catch up to appraised values, but the net result will be a much smaller tax base and lower municipal revenues. Other negative consequences include empty, potentially blighted buildings accompanied by less foot traffic and potential safety concerns.

Many question whether office workers will eventually return to traditional office locations, such as central business districts. We believe that the vast majority of workers will utilize traditional office space 3–5 days per week, although there is certainly risk around this assumption, particularly if transit and other services are not kept up. Even with returning workers, some CBD office buildings are effectively obsolete, and [they] will need to be torn down or repurposed as residential, hospitality, or other uses. These are difficult projects to undertake, and [they] will likely require some combination of very low building prices and government resources such as loans and tax breaks. Cities have been replacing older buildings and reinventing themselves for centuries, and [they] will likely continue doing so in the future.

Rebecca Rockey, deputy chief economist, global head of forecasting, Cushman & Wakefield

The distress cycle in [commercial real estate] has its own cadence and tends to lag the broader capital markets cycle, in which volumes and prices trough and start rising broadly, yet distress continues to increase, as well. It is very likely that this is how things will play out over the coming years. To that end, a pickup in office distress in particular has a few implications.

Of note is that about half of office real estate is in CBDs, in a very concentrated area, while the other half is in suburbs over a greater area, so there will also be real impacts for central cities. The unfurling of the office distress cycle means that unrealized losses will finally materialize, and some investors will lose. The degree to which lenders lose will vary on an asset-by-asset basis, and to that end, capital reserves against loan losses continue to rise broadly since, on net, there will be losses.

This [outcome] presents a unique moment for cities, and downtowns specifically, to really consider whether office is the highest and best value use of that land and real estate, and to possibly hasten or accelerate the recognition of today’s true value and its potential. In the aggregate, when looking at what owners are doing with office assets, most are not converting—they are doing complete renovations or repositionings with a view that higher-quality space will be scarce, given [that] the new construction pipeline has dropped off a cliff. Yes, some are converting to residential—as are some hotels—which is a positive for markets, both to address a housing deficit and also bring residents to an area.

We all know that [conversion] is expensive and difficult—although I encourage people to not use that as a crutch [and] to acknowledge that office stock needs to change, and it’s just a matter of time, price, and policy. At the right basis, with the right engagement from the city and planning boards, and with the right incentives, capital sources, and so forth—even if demolition is part of the equation—there will be a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reimagine cities and downtowns in particular, which have a tremendous reliance on office. Some of that reimagining will still include office, but I expect to see more emphasis on mixed-use. We estimated what we think could be optimal, with a strong infusion of experience to draw foot traffic seven days a week and outside of 9–5 work hours. The benefits of this kind of repositioning cannot be understated for the local economy, the public sector and taxpayers, and investors.

My view is that in certain instances, strategic acquisitions of adjacent land or buildings could unlock megascale opportunities for investors and developers—and cities themselves—to think bigger and more holistically. I am seeing inklings of this emerging, which makes me really excited for the next chapter.

Christopher Thornberg, founding partner, Beacon Economics

While the pandemic may have sped things up, the current distress in U.S. office markets actually began more than two decades ago, with the release of the first BlackBerry, at the end of the 1990s. Untethering access to information and people from the physical space of an office has naturally reduced (but not removed) the need for offices on a per-employee basis. While offices are still a core asset to any city, the result of this shift means the gross ratio of office space needed, relative to other land uses, must be reduced to maintain a healthy urban environment.

This [shift] can take place through infill development around existing offices and/or by converting or demolishing them for new uses—thinning the herd. Unfortunately, the economic weakness created in local economies by low office utilization is, by itself, a large disincentive for such expensive reinvestments. And, of course, there are enormous regulatory hurdles and zoning constraints in most dense urban areas that can delay or prevent necessary reform. Add it up and we have a recipe for a serious decline in our nation’s urban centers. Any solution will require strong local leadership willing to spearhead major changes in local land use systems. Sadly, strong effective leadership around this issue has been in low supply in recent years.

Related Reading: