Market demand is the best driver for innovation, and Patrick Otellini—chief resilience officer for the city and county of San Francisco—is among those making a case that the intrinsic economic value of resilient design will help drive its acceptance.

“I think inclusion of resilient design strategies will become standard at some point because people want it,” Otellini says.

“When green building design first came on the development scene, I was at the U.S. Green Building Council, and we saw that developers resisted the LEED [Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design] rating system as just adding charges,” he notes. “But tenants began asking for and demanding LEED buildings, and today it’s practically a minimum standard.”

The collision of forces between the need for resilience and the cost of it is producing sparks of creativity, particularly in the area of waterfront and storm-related planning.

In development examples from New York to New Orleans and San Francisco, the real estate industry is undertaking new solutions and adjusting old ones to demonstrate that storm-related and sea-rise resilience can be leveraged into user amenities and community benefits, making dollars stretch further. Far from a defensive role, resilience can be part of a project’s marketing strategy and mission.

“Some developers are making the strategic decision to not purchase on waterfronts or in flood zones, and yet other projects close to water are choosing to demonstrate innovation and lead the way because people love being near the water,” says Deb Guenther, a partner and landscape architect at integrated design firm Mithun in Seattle. “Water is a magnet.”

New Orleans Strategies

In New Orleans, the unprecedented damage caused by Hurricane Katrina is yielding to a new foundation of building strategies that respect nature while providing recreation, connectivity, and community engagement.

Related: ULX Waterfront Open Space

Lafitte Greenway is a new 2.6-mile (4 km) linear park that opened in November 2015 with a multiuse bicycle and pedestrian trail along a former canal and railroad, stretching from the French Quarter to the Tremé and Mid-City neighborhoods with connectivity to New Orleans’s large urban green space, City Park. The Greenway is also an amenitized infrastructure project that is becoming a magnet for residential and commercial improvements. Amenities for visitors include a 12-foot-wide (3.7 m) multiuse path, LED energy-efficent trail lighting, more than 500 trees, new recreation fields, high-visibility crosswalks, bike racks, children’s play areas, and stormwater management features including bioswales and native plant meadows.

The Greenway’s emphasis on green spaces is part of a citywide storm resilience strategy to hold more rainfall on site to send it back into the water table, says Jeff Hebert, chief resilience officer for the city of New Orleans.

“Unlike other cities, New Orleans has levees holding water out around us, and water inside has to be pumped out,” he says. “In a storm event, we need to have the least stress on our pumping systems, including having less [water] filling up storm sewers. Another major issue for New Orleans is subsidence that’s been caused by years of pumping water out when some of it should be recharging groundwater.”

The Greenway is also designed to be an economic catalyst and community connector, which enhances the neighborhood’s resilience as well, he notes.

“The Greenway is truly a transformative development for New Orleans,” said Susan G. Guidry, a member of city council, at the November 2015 dedication of the hike and bike paths. “Connecting historic neighborhoods through four council districts, the Greenway establishes a new corridor for transportation, health, neighborhood business, and community development in the heart of our city.”

Development around the Greenway is taking hold in public, private, and joint venture projects. “The new way that we are looking at long-term infrastructure projects is to make the very most out of them with parks or green space or whatever else we can do to help attract more economic development, jobs, and housing,” Hebert says.

In June 2016, private developer IV Capital of New Orleans and its partner, Edwards Communities of Dublin, Ohio, won unanimous planning commission approval for 382 apartments over retail space on nearly nine acres (3.6 ha) off the Lafitte Greenway at Bayou St. Jean, taking advantage of the Greenway adjacency with its own pedestrian- and bike-friendly design, green spaces, and stormwater management. Expecting to start construction by late 2016, lead partner and local entrepreneur Sidney Torres IV envisions the community to include kayaks along the bayou, fire pits on the bank, children’s playgrounds, and bike paths. An adjacent site he controls has been approved to become a retail center.

A project in the 1,300-acre (526 ha) City Park, the Louisiana Children’s Museum, offers resilience best practices in a city whose culture is formed by land and water.

The project is being developed by the Louisiana Children’s Museum, with key funding sources including significant private sector donations, the land sale of its existing urban facility, as well as a $17 million capital outlay from the state of Louisiana. The partnership model and related programming of the museum are intended to meet a variety of needs by stretching dollars across the multiple benefits of literacy, childhood development, family health, environmental education, and green infrastructure. Not only is it aimed to attract local visitors and out-of-state tourists as did its former urban location, the new Louisiana Children’s Museum and its eight-acre (3.2 ha) outdoor environment will enhance native habitat, provide food and children’s nutrition education via the site’s edible garden, and broaden environmental education through its nature center and schoolteacher resource center.

“It is important for children and everyone to understand the ecosystems of south Louisiana, especially in a state with so many natural resources,” says Julia Bland, the executive director. “We are thrilled to have a place that brings families into an immersive experience with nature and have a regional model for resilient design. It’s the best of both worlds.”

The 56,000-square-foot (5,200 sq m) facility fronts a lagoon built in the 1930s, part of the park’s 113-acre (46 ha) system of manmade water features of water flowing from Bayou St. John to Lake Pontchartrain. The lagoons were hand dug as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) improvements during the Great Depression.

Designed to attain a LEED Silver rating, the museum design is being led by Mithun’s team of architects, landscape architects, and interior designers in collaboration with Waggonner & Ball Architects, ARUP, Thornton Thomasetti, Pastorek Habitats, Schrenk Endom Flanagan civil engineer, and exhibit design firm Gyroscope Inc.

The project, starting construction later this year and opening in 2018, is designed to maintain its natural drainage with curbless parking, bioswales, and improved soils that will hold more water. Some 1.7 million gallons (6.4 million liters) of rainwater from the roof of the north wing and the parking area will be filtered through the natural drainage system each year. A portion of this rainwater will run through two 12,000-gallon (55,000 liters) cisterns, one for children’s play and one for toilet flushing.

Fresh and brackish marshlands are being created along the edge of the existing lake to provide habitat and reduce erosion caused by surface water. The building will be located five feet (1.5 m) above grade to prevent flooding and perch above the system of bioswales. The project is also designed with access via multiple paths so that the site can be used immediately after storms.

A primary resilience strategy is that the site is designed to adapt to the New Orleans Water Plan, which, when fully implemented, would reduce flooding in surrounding neighborhoods by increasing stormwater retention capacity on this site and others in City Park.

The new museum also demonstrates how a cost-conscious nonprofit organization can make resilience affordable by leveraging the stormwater demands of a site to create landscape features and site amenities that are integral to the institution’s teaching mission.

“The Children’s Museum has worked closely with the city’s resiliency recommendations, and [it] will be a great project for demonstrating advanced techniques in water resource management and storm-related resilience, even as it becomes a great destination for visitors,” says Hebert.

New York Waterfronts: Resilient Retrofit and Renewal

In post–Hurricane Sandy New York, a series of municipal code changes and recommendations are leading to resilience best practices such as raising ground floors, elevating critical power and infrastructure systems on roofs and upper floors, cladding and bolstering building exteriors especially at lower levels, and pushing properties back from the water’s edge. This last technique also creates opportunities for water resource strategies such as shoreline-buffering wetlands and bioswales to cleanse street runoff, and is a boon for creating landscaped, amenitized space.

Hunter’s Point South Park is a 30-acre (12 ha) mixed-use development with a ten-acre (4 ha) city park along the Queens waterfront by Thomas Balsley Associates and Weiss/Manfredi with Arup as prime infrastructure consultant. While the park space predates the area’s redevelopment, its complete redesign and construction after the damage inflicted by Hurricane Sandy were an integral consideration in also providing a storm protection buffer during extreme weather, according to Vincent Lee, associate principal at Arup. But New Yorkers primarily enjoy the popular park as a generous pedestrian and sports/play area, a gathering space for the community, and a visual frame for adjacent high-rise development.

Behind the park is Hunter’s Point South, a $350 million mixed-use complex of affordable/workforce housing, retail space, and a school. The project is by the Related Companies, affordable housing builder Phipps Houses, and Monadnock Construction.

Waterfront green space, such as the Hunter’s Point park’s buffer role for the massive new mixed-use project, illustrates a reversal of earlier development strategies that pushed projects to the water’s edge to maximize a property’s views, user access, and income potential.

But building away from the water’s edge should become more of the norm if not a requirement, according to Lee.

“There’s tension along the waterfront because that’s where people and developers want to be,” said Lee, “but it’s also the impact zone in a storm. Now, more development and redevelopment proposals are encompassing landscape surroundings and blue-green infrastructure.”

Landscape and infrastructure as a resilience amenity are also at work off the Atlantic Ocean shoreline.

Located a block from the boardwalk and beach in the Far Rockaway area of Queens, the 101-unit Beach Green North apartments, now under construction with an expected April 2017 completion date, “is at the forefront of sustainability and resiliency,” says Steve Bluestone, partner at the Bluestone Organization, the developer. “Built to the Passive House standard and in excess of current FEMA and building code requirements, residents will live more comfortably and safely in the event of future storms and potential sea-level rise.” The design for the project was done by Curtis + Ginsberg Architects.

Among the amenities of this affordable housing are a rooftop garden alongside an upper-floor terrace with views of the beach and ocean. Native species plantings and bioswales at the ground level and rear raised terrace areas will retain stormwater runoff and provide a supply of on-site water for irrigation. Also, insulated concrete form (ICF) construction used on exterior walls provides a comfortable, resilient, air-tight structure and drastically lower heating and cooling costs for tenants.

A major next phase at Beach Green involves an 80-acre (32 ha) site that is the largest undeveloped coastline parcel in New York City. Now in planning, the 1,500-unit housing community with 150,000 square feet (13,900 sq m) of commercial space will also serve the greater Rockaways community as a resilient “safe haven” by using a combination of on-site solar and wind energy production systems as well as an advanced membrane bioreactor and anaerobic bio-digester system allowing for zero sanitary/storm waste leaving the site.

A new Rockaway beach boardwalk that was ravaged by Superstorm Sandy was fully connected on Memorial Day 2016, and all sections of a new and innovative DuneWalk will be rebuilt by 2017. It will be the longest and largest contiguous resilience project completed to date by the city of New York.

Under an overall project called DuneWalk, it includes the first large-scale promenade built new since the Robert Moses era.

“The iconic curving plank design has struck a chord with a community devastated by Hurricane Sandy that desired their landmark to be returned to its former greatness as a destination,” says Claire Weisz of WXY architecture + urban design, the project designer.

At eight feet (2.4 m) high and 5.5 miles (8.9 km) long, the Rockaway boardwalk includes new, publicly initiated design features, including NYC light by Thomas Phifer, WXY’s 2030 drinking fountain, and custom decks and furnishings using salvaged wood. Letters spelling out ROCKAWAY are visible from the sky, glowing blue at night.

“The boardwalk sets a global standard for resilient shoreline design, while providing the Rockaway community with a beautiful, functional beachfront,” according to a park department statement announcing the summer 2016 completion.

The boardwalk uses a steel-reinforced concrete deck fixed to steel pipe support piles, elevating the promenade above the 100-year floodplain. It is protected by six miles (9.7 km) of planted dunes and is in the process of receiving a concrete retaining wall on the beach and out of the neighboring communities.

Does resilient design work?

“It’s perhaps counterintuitive, but among the safest places to have been during Hurricane Sandy was right on the coast,” says Dan Zarrilli, senior director of climate policy and programs for the city of New York. “We saw during the storm that structures built to the latest codes fared well, while older structures were devastated.”

San Francisco: Sea Level Raising Parks

Large San Francisco waterfront developments are implementing resilience as an amenity vehicle, incorporating needed responses to sea rise while turning many of those response strategies into benefits for people and the environment.

“Virtually all of San Francisco Bay’s natural shorelines have been lost over time, but there are new opportunities to redesign and bring back the environmental benefits and improve access for people,” says Kevin Conger of CMG Landscape Architecture, which worked on Mission Rock, Treasure Island, and other waterfront projects there. “Resilience design for sea rise and storm consideration is a project-by-project approach. It’s not cheap but offers enormous potential.”

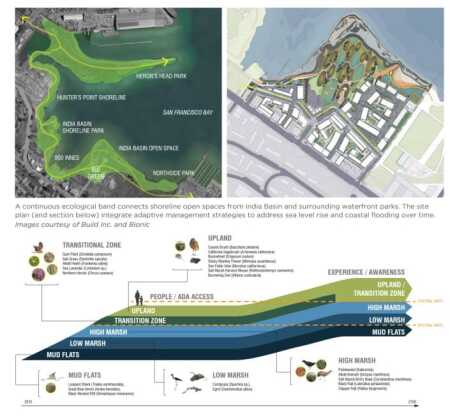

The 17-acre (6.9 ha) India Basin mixed-use development located five miles (8 km) south of the Financial District on San Francisco’s Southeast Waterfront is a project by BUILD, a San Francisco development and investment firm whose stated mission is to create great urban places that benefit the community and its co-investors. The project, expected to obtain entitlements in 2017 with groundbreaking in 2018, will include over 1,200 residential units, with as many as 20 percent of them subsidized affordable, and will include retail and arts/education space. More than five acres (2 ha) of the project is open space, primarily along the waterfront.

“Our project is serving as the economic catalyst for a larger adaptive strategy,” says Michael Yarne, principal at BUILD. “This is a public/private partnership with our planning and design efforts extending out beyond our property to 7.5 acres [3 ha] of public right-of-way and 6.2 acres (2.5 ha) of open space owned by the city of San Francisco. And we’re helping fund entitlements and designs for the adjacent 900 Innes and India Basin Shoreline Park, which total another eight acres [3.2 ha].” Shoreline Park and 900 Innes are city-controlled Recreation and Parks Department green-space sites adjacent to BUILD’s project that are included as part of its environmental impact report.

Designed with consultants Bionic Landscape Architecture and Gehl Architects, plans for the combined India Basin parks and green space incorporate terraced wetlands into the existing banks for upland habitat migration and as a means to augment habitat loss occurring elsewhere in the basin. There are current wetlands on the 6.2 acres [2.5 ha] of open space between BUIILD’s property and the bay that are separated by a significant grade change or bank. The design team plans to use this bank as a storm buffer area and enhanced native habitat (see appended graphic below).

At the basin scale, a continuous shoreline band over one mile (1.6 km) long is planned to test living shoreline strategies and establish habitat along the entire waterfront.

“In the face of rising tides, our India Basin design is analyzing living-shoreline strategies to create an adaptive and resilient waterfront with a 100-year horizon,” says Courtney Pash, senior project manager for BUILD. “In the big picture, we see it providing overall triple-bottom-line benefits—for people, the environment, and economic success—along the entire waterfront.”

At Mission Rock, another private sector development a mile (1.6 km) north of India Basin along the same bay waterfront, plans call for a vibrant, active waterfront park as a key feature of a publicly accessible open space fronting the 27-acre (11 ha) mixed-use project. A citywide ballot measure in November 2015 gave voter approval for the project’s inland buildings to rise higher than height limits previously set for the site, supporting the commercial, residential, and green-space development. A project of the San Francisco Giants converting existing parking lots and adjacent spaces, Mission Rock residential units will be 40 percent affordable housing.

Mission Rock’s accommodation to sea-rise concerns, developed in conjunction with the Port of San Francisco in conjunction with the Bay Conservation and Development Commission and other agencies, includes a topographic strategy to create a variety of zones, from the highest, designed to be above 100-year floods, to the lower zones that will accommodate natural water-level fluctuation amid a combination of wetlands, native habitat spaces, waterfront promenades, and programmed, accessible open space.

At Treasure Island in the middle of San Francisco Bay, construction began in March 2016 on first-phase infrastructure for the conversion of the former military base over the next 20 years into a $1.5 billion mixed-use neighborhood. A venture of Wilson Meany, Stockbridge Real Estate Funds, Lennar Corporation, and Kenwood Investments, it will have a mixture of high-rise commercial/residential areas and more than 300 acres (121 ha) of green space. Much of the open space is along waterfronts featuring public access and parks as well as restored shoreline, wetlands, and native habitat.

Waterfront Resilience, Amenities, Social Cohesion

“Water, open space, and the development are where people ultimately want to be and gather, whether for exercise, shopping and dining, to see distant views, or to experience the theater of the working waterfront,” says Todd Kohli, planning and landscape architecture principal with Populous San Francisco. “Coastal resilience can be strengthened by integrating smart design and development—allowing the public to experience the draws of the waterfront while protecting community assets.”

Development strategies incorporating human benefits into planning for catastrophes go beyond waterfront parks and habitat, of course.

A growing consensus of resilience strategies are taking a holistic look at the problem, recommending that public and private sector plans consider not just construction techniques but also community resilience, local government leadership, and social systems that provide tools for minimizing the impact of these challenges, and speed the recovery.

“Social cohesion is another cornerstone of resilience strategies,” says Mithun’s Guenther. “When people are connected with their neighbors, it reinforces personal commitment to the neighborhood and increases capacity of cities to recover from natural disasters. How cities and developers are connecting people can’t be overestimated in resilience strategies.”

In the pursuit of best practices in design for resilience, the components of new and redeveloped projects that can be leveraged into private and public amenities are a key strategy for obtaining public support, community engagement and connectivity, environmental benefits, and long-term economic success.

After all, it’s about what tenants, residents, and shoppers demand, and resilience is moving up the list.

For additional information on how parks and open space can support stormwater management and environmental resilience, sign up for updates on the 10 Minute Walk Campaign or follow #10MinWalk. The 10-Minute Walk Campaign, a national movement led by the Urban Land Institute, The Trust for Public Land, and the National Recreation and Park Association, is promoting the bold idea that everyone living in urban America should live within a 10-minute walk of a park.