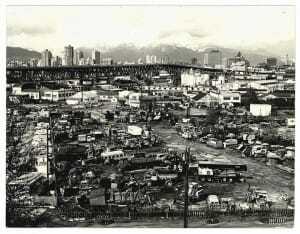

In the early 1970s, Ron Basford, a Canadian Cabinet minister and loyal Vancouverite, seized on the idea of converting Granville Island—a modestly sized pancake barely a half mile (0.8 km) south of the emerging downtown—into a special place. Until the mid—20th century, the island had prospered as an industrial hotbed, jammed with shipyards, metal fabricators, wire rope manufacturers, and warehouses. But with the shift in the post–World War II economy away from industrial production, tenants departed, leaving the island derelict and the remaining structures vulnerable to arson.

Basford wanted the island to be owned, managed, and financed by the Canadian government. He also wanted to vest policy and creative thinking in the hands of the Granville Island Trust, a core of locally committed civic leaders and urban experts. He succeeded on both accounts.

The launch of the Granville Island Public Market in 1979 was the first in a succession of adaptive use projects meant to capture a distinct identity—a local identity—for the island’s revival. A sense of place has been central to the island’s subsequent success. The most recent figures (2009) show 85 percent of the island’s annual visits are from metro Vancouver, and almost half of those frequent the Public Market’s many vendors for their normal fresh food needs. Travel guides, on the other hand, continue to trumpet the 10 million total annual visits as proof that the island is Canada’s number-one tourist attraction. How to strike the right balance between these two user groups is the subject of ongoing debate.

Granville was never intended to be a theme park or to mirror the festival marketplace brand. Nor was it intended to conform to a master plan. Change has been incremental, but deliberate. The island’s founding principles for redevelopment, design guidelines, desire for a broad diversity of activities, governance, and financing have all been based on the premise that place making take precedence over profit.

Redevelopment was initially financed by federal grants with no payback requirements, the main restriction being that the island not be allowed to operate at a deficit. In subsequent years, annual operating surpluses have generally been less than $1 million—sums reinvested in the island rather than deposited in the federal treasury. However, reinvestment in site upgrades and infrastructure has lagged in recent years, and several development sites remain underused.

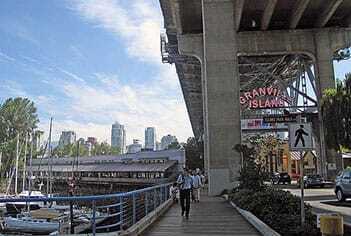

The ongoing application of the island’s redesign is widely admired. Design guidelines and design review, as administered by architect Norm Hotson, are based on retaining the vernacular of gable-roofed sheds and corrugated-metal siding on once-gritty buildings. Industrial-scaled entries, on-site cranes, and even the original rail tracks remain in place as references to the site’s industrial heritage.

There are no sidewalks on Granville Island. The streetscape design is modeled loosely on the Dutch woonerf concept, in which the street functions as a social space, allowing slow-moving vehicles, cyclists, and pedestrians to cross paths somewhat randomly. A consistent but flexible palette of signs, canvas awnings, and timber bollards recalls the island’s nautical and industrial history. Utility lines are hidden inside bold, color-coded metal piping that zigzags overhead from block to block.

Granville Island’s broad range of activities is intended to provide a complementary mix that does not detract from existing submarkets elsewhere in Vancouver. In addition to 50 tenants and 30 day vendors in the Public Market, about 200 are located elsewhere along the island’s cul-de-sac streets. A thriving maritime facility, numerous restaurants and eateries, child-centered shopping and play areas, a smattering of houseboats, and six performance venues are packed onto the island’s 34 acres (13.75 ha). Emily Carr University of Art and Design, enrolling 1,800 students, has functioned for decades as a second anchor and as a cultural and educational complement to the Public Market.

A key policy and leasing strategy is to forbid franchised retailers: there are no Big Macs on Granville Island. The island has also maintained a balance between profitable retail operations and cross-subsidized arts and cultural activities—what Granville Island Trust chair Dale McClanaghan has dubbed the “Robin Hood” approach to leasing.

But concerns about the island’s future are growing. The most immediate issue is marketing the Emily Carr University property; the university announced last year it would move to nearby Great Northern Way, having outgrown the island site.

Some observers believe that the federal agency managing Granville Island, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), has lowered the standards of design oversight in recent years and that CMHC may not be taking adequate precautions to exclude undesirable commercial tenants, such as a souvenir clothing shop and a psychic studio. McClanaghan wants the Granville Island Trust to reassert its original role governing vision and policy within the context of an improved financial framework to develop as-yet-unused tenant space.

Hotson and McClanaghan agree that Granville Island may be at a turning point in its evolution. Though the island is listed among 60 of the World’s Great Places by the Project for Public Spaces, issues of the island’s vulnerability continue to surface. The challenge now is whether a long-discussed return of local leadership to the Granville Island Trust can help reinvigorate the island without sacrificing allegiance to its founding principles.

Martin Zimmerman directs the Green Mobility Planning Studio USA—a firm with expertise in smart growth, urban place making, and multimodal transportation—from Charlotte, North Carolina. When in Vancouver, he bikes to Granville Island.