Every night, more than 50,000 New York City residents, including 22,000 children, sleep in the city’s homeless shelter system—an all-time high. That is just one—though the most extreme—indicator of the seriousness of the city’s greatest housing problem.

“We have a crisis of affordability,” says Mayor Bill de Blasio, who took office earlier this year.

Related: Placing a Priority on New York’s—and the Nation’s—Rental Housing | Register for the ULI Fall Meeting in NYC

This spring, he released a massive ten-year plan responding to New York’s housing crisis. He promises to bring to the city new housing that is affordable to every income level—including hundreds of thousands of units of privately managed affordable housing. It is the largest plan in decades aimed at bringing new affordable housing to the city and keeping the affordable housing the city already has.

“People are very excited about the plan,” says Judy Calogero, chief executive officer of the New York Housing Conference, a local housing advocacy group.

Worsening Crisis

New York City has one of the strongest housing markets in the country, to judge by the demand for real estate. Investors from all over the world are eager to buy property. But for people who actually live in New York, it has become increasingly difficult to find an affordable place to live despite decades of effort by officials and housing advocates to create new affordable housing.

Since 2008, more than half of all rental households in the city have spent more than 30 percent of their household income on rent, according to an analysis by the Furman Center at New York University. Nearly one-third dedicate more than half their income to rent. The burden of high rent affects nearly every income group in every neighborhood as a growing number of New Yorkers bid against each other for too few apartments. Over the past 20 years, the average monthly rent for an apartment in New York City increased by almost 40 percent, adjusted for inflation, according to city officials; during the same period, wages for the city’s renters rose by less than 15 percent.

In much of the city, rents rose even during the financial crisis, as well as during the long, slow recovery that has followed. Between 2005 and 2012, rents rose 19 percent in Manhattan, and only Staten Island among the city’s five boroughs saw rents fall—by 3 percent, according to the Furman Center.

De Blasio’s housing team released its plan to deal with the crisis in May, just a few months after the administration took office. The sheer size of the plan, with well over 100 pages of detailed policy promises, surprised advocates. “This is a great, out-of-the-gate commitment,” says Kristin Miller, director of CSH, a supportive housing advocacy group. “We like to see that momentum.”

De Blasio’s plan has much in common with the New Housing Marketplace plans first announced by his predecessor, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, more than a decade ago. “We really appreciate that we stand on the shoulders of giants,” says Vicki Been, commissioner of New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. “We don’t have the luxury of being able to step in and do great things simply by being better. This is not a matter of ramping up our programs a bit. We have to push the envelope and invent new approaches.”

Both plans promise to preserve or create a huge quantity of affordable housing with formal income restrictions over a long period. The units would be built or renovated using a familiar mix of programs, including federal low-income housing tax credits and private-activity bonds, along with state and local funds. Both plans also use tools such as large-scale zoning changes and ask developers that take advantage of those changes to include significant amounts of new affordable housing in their product. Both plans also make preservation of existing affordable housing a priority.

However, the de Blasio plan has a much broader scale: it promises over the next ten years to build or preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing—80,000 new units and 120,000 existing ones. That is a significant increase from Bloomberg’s plan, launched in 2003 and then expanded, which built or preserved 165,000 units, which when announced seemed like a great amount of new housing.

“When we made the initial announcement, . . . people thought we were crazy,” says Gary Rodney, who served in the previous administration and is now president of New York’s Housing Development Corporation (HDC), the city agency that issues bonds backed by housing properties, including federal tax-exempt bonds.

The 200,000 housing units to be built or renovated under the de Blasio plan would be a huge amount of housing, largely completed by for-profit local developers and nonprofit community development corporations. The plan would total more housing units than New York City’s existing stock of 180,000 government-built and government-owned public housing apartments. The planned 200,000 units also would constitute more than 5 percent of New York City’s entire housing stock of 3.4 million units.

Simply building more housing is an inevitable part of any plan to address New York City’s housing crisis. The city’s population is anticipated to climb to 9 million by 2040 from more than 8 million today. If new stock is not built, the new residents will bid up New York’s already-high prices as they compete for limited supply. “We are never going to reach a solution to the problem if we don’t build more,” says Been.

The mayor’s plan would continue to find new places for people at all income levels to live, changing the zoning laws in neighborhoods to allow developers to build more housing. To get neighborhoods to accept these new developments, city officials plan to include residents in the process for deciding what the new housing would look like and where it would go. “We have to have a new way of thinking about density and talking with communities about density,” says Been.

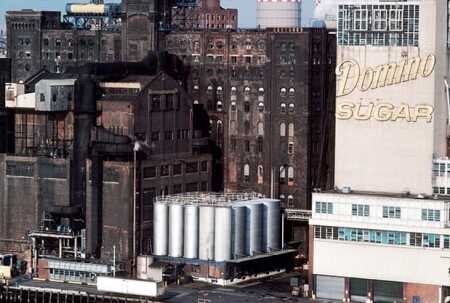

Mayor Bill de Blasio struck a deal with Domino Sugar plant site developer Jed Walentas to add 50,000 square feet (4,600 sq m) of affordable housing to the planned $1.5 billion office, retail, and residential complex. The additional 40 affordable units, allowing more two- and three-bedroom apartments, will bring the total to 700 affordable units among the 2,300 total housing units planned at the site. (© Paul Martinka/Splash News/Corbis)

The Treadmill of Development

However, it will take more than a lot of new apartments to end New York’s affordability crisis. “You can’t just build your way out of a crisis,” says Been. For example, the Bloomberg housing plan met its goals to build and preserve 135,000 affordable housing units—but housing in New York City is now less affordable that when the plan was announced, according to the Furman analysis.

In part, New York City is hindered by its success. It has decisively won its battle against blight and urban decay, in part thanks to a massive investment in housing begun by Ed Koch, mayor from 1978 to 1989. In the 1970s and 1980s, the city had lost more than 350,000 housing units to abandonment; property owners simply walked away, and without basic maintenance, fire and rain destroyed thousands of buildings. Eventually, the city seized the properties for unpaid property taxes. The city has now returned all those city-owned properties to productive use, often as affordable-housing properties, many of which helped stabilize their neighborhoods and improved property values around them.

Once notoriously unsafe neighborhoods like Alphabet City in Manhattan and Bedford Stuyvesant in Brooklyn are now increasingly desirable. Brownstone homes abandoned a few decades ago now routinely sell at prices topping $1 million.

“We have rebuilt neighborhoods, and these places are no longer affordable,” says Kirk Goodrich, director of development of Monadnock Construction, a Brooklyn-based general contractor and construction management firm.

While new affordable housing helps alleviate New York’s massive, pent-up demand for housing, it can also increase that demand. “The more we make housing affordable, the more people will want to come to New York,” says Been.

New York’s growing desirability also threatens existing affordable housing. During the real estate boom, speculators paid top dollar to buy older apartments and did everything they could to raise the rents. For instance, investors paid nearly a half-million dollars per apartment for the massive Stuyvesant Town property, built in the 1940s as homes for returning veterans. They planned to renovate these properties and sharply raise the rents. Transactions like this were so common that housing advocates created a name for the strategy—predatory equity.

Many of the buildings targeted by predatory equity were in one or more federal or state affordable housing programs. Speculators bought these buildings, exercised their option to opt out of the programs, and tried to raise the rents. Rent stabilization limits rent increases for existing residents, but an empty apartment can be renovated to allow much higher rents, so the new landlords hunted for residents who could be evicted for breaking the terms of their leases. But the plans often failed. The city’s rent regulations often proved much tougher than anticipated in blocking developers’ plans to evict tenants and raise rents, and many giant properties were eventually seized by lenders in foreclosure. But along the way speculators removed thousands of units of housing from affordable housing programs.

Largely because of predatory equity, New York City finished the Bloomberg housing plan with roughly the same amount of income-restricted affordable housing it started with, despite building and preserving a tremendous amount of housing. “A lot of units were lost—not for lack of trying,” says Calogero.

As the national economy improves and real estate markets heat up, housing advocates worry a second wave of predatory equity might be coming to the city. “If we are not preserving affordable housing, we are never going to get out of the crisis,” says Rodney. Officials are keeping a close eye on the existing stock of affordable housing, watching for complaints from residents about harassment from owners attempting to evict them and making sure that any new owners fully understand the complexity and strength of the city’s rent laws and the potential opportunities, such as capital and operating subsidies offered to property owners that stay in the city’s affordable housing programs.

Unique New York

New York’s desirability does not just present a challenge for construction of affordable housing; it is also a strength. One of the most important sources of funding for this construction, for example, depends on the involvement of for-profit investors. Because of New York’s strong housing market, these investors pay significantly higher prices for low-income housing tax credits from New York City projects than are paid practically anywhere else. That generates more cash to build more affordable housing.

New York’s strong economy and strengthening real estate market also make it easier for the city government to raise money by issuing housing bonds. “We continue to have increased interest in the market when selling our bonds,” says Rodney. “That helps with the cost of capital and allows us to do more.” In eight of the past ten years, the HDC has been the biggest multifamily bond issuer in the country.

New York City will need all those advantages and more to meet the bold, 200,000-unit target laid out in the new housing plan. Advocates still worry that the plan may prove impossible to finance. “There is some hesitancy about where the money is coming from,” says Calogero. “Funding is going to be an issue.”

In the time since the city met the challenge established in the Bloomberg housing plan, federal funding that helped finance that plan has been cut deeply, including HOME funds and community development block grants.

But New York City’s housing officials have already started to answer the funding question. In July, the mayor’s office announced $350 million in new funding for affordable housing from investors including Citibank, Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank, and Bank of America, which would invest through the Community Preservation Corporation, a nonprofit organization that brings private investment to affordable housing properties throughout New York state. The money, being added to the affordable housing investments these investors already make, will help finance 7,500 units of housing, providing about $47,000 per unit that likely will be paired with cash from federal programs.

City officials are also planning to raise more money to develop affordable housing by issuing new tax-exempt 501(c)(3) bonds and reissuing tax-exempt bonds that are paid back early, among other strategies.

The high value of New York’s real estate also makes it possible for the city to ask developers to include significant amounts of affordable housing in their new projects in exchange for the right to build those projects on a larger scale. This strategy, called inclusionary zoning, was used by the Bloomberg administration, but housing officials now plan to take a tougher stance in negotiations, demanding more affordable housing from developers building in the strongest neighborhoods. And housing advocates still worry about where the money will come from to support these affordable housing units. “We don’t have the subsidy to fill those larger projects,” says Calogero.

Big Changes

But even these advantages will not be enough to end New York City’s crisis of affordable housing. “We have to cast a wide net,” says Rodney. “How do you reach everyone?”

To answer that question, advocates and officials are questioning the makeup of the housing they develop. For example, though single people constitute a large portion of renter households in New York, the current housing policy requires a unit mix that favors larger, two-bedroom apartments. To address this, the city plans to amend its policies to encourage the development of more studio apartments.

Some housing advocates go further, calling for the city to once again allow renters to legally rent single rooms. Single-room-occupancy housing has been illegal in New York for decades. Advocates also call for the city to allow micro-housing—apartments providing less than 400 square feet (37 sq m) of space.

Also being considered by officials are programs to preserve the affordability of houses. Visitors to New York City might be surprised to discover that large parts of the city are dominated by houses, especially in the outer boroughs. Three-quarters of the city’s low-income households who do not live in subsidized housing live in two- to five-family houses. “That is just a critical stock that we have to learn to deal with,” says Been.

The city is continuing to focus on specific populations with special needs, such as seniors and the chronically homeless. The city is negotiating a possible new round of supportive housing development through the New York/New York Agreement, which in its last round, New York/New York III, provided capital and operating funds to build, renovate, acquire, and run 9,000 supportive housing units, often helping people at risk of becoming homeless.

Affordable housing is also linked to economic development. If the average income of city residents falls, then the housing will become less affordable. Conversely, the city’s economy will weaken if talented people cannot afford to live there.

In that sense, building affordable housing is no longer only about redeveloping abandoned properties and stabilizing dangerous neighborhoods. “It becomes an economic development play,” says Calogero.

A new deputy mayor, Alicia Glen, is expected to make the link between housing and economic development explicit. “This is the first time that the deputy mayor’s title has included both housing and economic development,” says Been. “That is incredibly important.”

New York City’s housing officials also have to look beyond the borders of the city. Big changes in Washington could threaten the city’s whole plan. As Congress considers comprehensive reform of the tax code, housing programs that New York City depends on could be at risk. “You are not going to accomplish the plan’s goals without federal low-income housing tax credits. You are not going to be able to do this without tax-exempt bond financing,” says Calogero.

No one expects lawmakers to wipe out the current generation of affordable housing programs. However, Congress can be full of surprises: when members passed the last big reform of the tax code in 1986, it ended an entire generation of federal affordable housing programs. Affordable housing experts are not taking any chances on such change happening without their notice.

“We are in regular contact with our delegation in D.C. as well as HUD [U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development], Treasury, and national associations that share our concerns,” says Rodney. “Congressmen see the results of our work in some of their districts. It makes a difference.”

Bendix Anderson has been a writer for more than 12 years on the subject of commercial real estate, sustainable development, and affordable housing.