The state of green design in ten projects.

Defining sustainable design is like trying to pick up a drop of mercury with one’s fingers. The more one tries, the more the object slips away. Can an airport parking garage be considered green if it has enough photovoltaic panels on the roof, or is a structure devoted to facilitating fuel-burning transportation inherently unsustainable? Are green building codes being passed by governments across the country too stringent, or do they set the bar too low and encourage greenwashing? Should voluntary green rating systems focus primarily on energy efficiency and revoke certification if projected energy savings do not materialize within a year?

The following ten projects, all completed in the past four years, do not answer those questions. Sustainability is and will always be a moving target, defined and redefined in discussions involving designers, developers, the public sector, and communities. But the ten projects here do illustrate the variety of green design strategies and their wide applicability to different building types, from mammoth convention centers and office complexes to small-scale buildings for nonprofit organizations or retailers, and a water resource operations center. (The ten projects are listed alphabetically, not in any rank order.)

1. ANZ Centre

Melbourne, Australia

The new global headquarters of the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. (ANZ) in Melbourne’s Docklands has a gross floor area of 1.4 million square feet (130,000 sq m) and houses 6,500 people. Yet the facility generates much of its own power using natural gas–fired reciprocating engines, a 135-kilowatt rooftop photovoltaic array, and six vertical-axis wind turbines. Waste heat produced by energy generation and water from the nearby Yarra River are used to help heat and cool the building, while an on-site blackwater treatment system collects and recycles all wastewater for use in irrigation.

The building also employs passive design strategies, with a north–south orientation and exterior shading on the east and west facades. Designed by local architecture firm Hassell and Lend Lease and completed in 2010, the ANZ Centre received a 6 Star Green Star certification from the Green Building Council of Australia. ANZ worked with property group Lend Lease, based in Millers Point, New South Wales, Australia, to develop the facility.

2. Convention Centre Dublin

Dublin, Ireland

Part of the redevelopment of Dublin’s Spencer Dock, the Convention Centre Dublin is billed as the world’s first carbon-neutral convention center. Designed by Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates LLC of Hamden, Connecticut, the 494,000-square-foot (45,900-sq-m) facility is near a new tram line and station and multiple other transit modes. It was built with Ecocem cement, which uses recycled slag; the manufacturers use independently verified carbon offsets to balance the rest of the carbon emissions involved in producing the cement.

A thermal wheel heat recovery system and an ice storage thermal unit reduce energy use for heating and cooling the building, while an integrated building automated system monitors and fine-tunes the building’s energy use. Stacking the facility’s uses vertically reduced its footprint. A high-performance glass atrium allows daylight to penetrate all five levels. As part of a public/private partnership with the government, Treasury Holdings of Dublin led the private sector consortium that developed the center, which opened in 2010. It received a Very Good certification through the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM).

3. Ed Roberts Campus

Berkeley, California

Proximity to public transit is one of the most significant factors in reducing a building’s carbon footprint. It is also particularly crucial for people with disabilities. Created by a nonprofit coalition of disability rights organizations and located at the Ashby Bay Area Rapid Transit Station in Berkeley, the Ed Roberts Campus is focused on access. The facility includes office space, community meeting rooms, a fitness center, vocational training facilities, a café, and a child care center for children with disabilities. A semicircular plaza functions as a gathering place, a drop-off and entry space, and a transit plaza.

The glazed facade facing the plaza facilitates daylighting and reveals the helical ramp that provides access to the second floor. Sustainable strategies include high-efficiency heat pumps, in-slab hydronic radiant space conditioning, solar control, operable windows, reflective roofing, and sustainably harvested, recycled, and rapidly renewable materials. San Francisco–based Leddy Maytum Stacy designed the 85,000-square-foot (7,900-sq-m) facility, which opened in 2010.

4. Green Depot

New York, New York

When the Green Depot, a Brooklyn-based supplier of ecofriendly building supplies, decided to open its flagship retail store in Manhattan in a landmark YMCA building dating to 1885, the company wanted to practice what it preached. So in renovating the space, local architecture firm Mapos LLC hunted for opportunities to reuse materials whenever possible and raise customer awareness of the possibilities of going green.

Oak beams rescued from the demolition process were used in store fixture tables, and locally salvaged windows became custom-designed sliding dividers. Original tile from the old swimming pool was reused, and the pool itself became a storage room. The designers cut out slices of wall near the entrance to reveal green materials beneath, giving customers a sense of how sustainable design strategies function in practice. The high-efficiency boiler, split-system air handler, and lighting all conserve energy. Completed in 2009, the store received a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Commercial Interiors Platinum rating.

5. Ironbank

Auckland, New Zealand

At the edge of Auckland’s central business district, amid buildings dating to the Victorian and Edwardian eras, rises what looks like five towers of irregularly stacked concrete boxes. This is the Ironbank office/retail complex. Local firm RTA Studio broke up the mass of the building into towers so it fits better with its neighbors. Ground-floor retail spaces open to an internal courtyard, and a pedestrian path passes through the site. Parking is tucked underground in an automatic car stacking system that holds 95 vehicles.

Natural ventilation with nighttime purging provides fresh air and cooling, a stormwater collection system reuses water for low-flush toilets and landscape irrigation, and water is heated through solar power. Ninety-five percent of construction waste was recycled. Completed in 2009 for local developer Samson Corporation, Ironbank received a 5 Green Star–Office Built rating from the New Zealand Green Building Council.

6. Proximity Hotel

Greensboro, North Carolina

When guests take the elevator down to the lobby at the Proximity Hotel in Greensboro, momentum generates energy for the next trip up, thanks to regenerative-drive elevators. Most of the sustainable touches that earned the hotel a LEED Platinum rating are similarly invisible—except for the rooftop solar water heating system. The goal of local owner/operator Quaintance-Weaver Restaurants and Hotels was to make the 147-room Proximity look and function like a luxury hotel.

Centrepoint Architecture of Raleigh, North Carolina, designed the hotel with operable windows, extensive daylighting, a high level of recycled-content building materials, low-flow plumbing fixtures, an energy recovery system, and a geothermal energy system for the restaurant’s refrigerators. In addition, as part of the project the owner restored 700 feet (200 m) of a stream running alongside the property, with rebuilt banks and local plant species chosen to mitigate erosion. The hotel was completed in 2007.

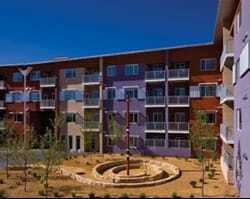

7. Silver Gardens

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Completion of the Alvarado Transportation Center in downtown Albuquerque, offering commuter-rail, Amtrak, and local and regional bus service, rendered the former Greyhound bus terminal across the street unnecessary. Because the downtown suffered from a shortage of affordable housing, the nonprofit housing organization Supportive Housing Coalition of New Mexico and developer Romero Rose LLC, both based in Albuquerque, teamed up to create the 66-unit Silver Gardens on the former Greyhound station site. Eighty-five percent of the apartments are affordable for those earning 30 to 60 percent of the area median income, with the rest renting at market rates.

Local firm Claudio Vigil Architects and Oz Architecture of Denver designed the four-story building with high-performance insulation and operable windows, high-efficiency mechanical systems, low-flow plumbing fixtures, and recycled and recyclable materials. It is the first U.S. project to receive funding from the Columbia, Maryland–based Enterprise Green Communities Offset Fund, which pays for projected emissions reductions resulting from sustainable strategies. The LEED Platinum–certified structure was completed in 2010.

8. Tempe Transportation Center

Tempe, Arizona

Getting people out of their cars and onto public transit can be a challenge in extreme climates, such as Phoenix’s desert metropolitan area. The Tempe Transportation Center, which opened at the end of 2008 at the same time as the Valley Metro light-rail line, beats the heat in a number of ways. The three-story mixed-use facility offers a well-shaded exterior courtyard and transit plaza, and a variety of strategies mitigate solar heat gain, including insulated low-emissivity glass, a mostly windowless concrete masonry wall to the west, and retractable exterior shade screens to the east that automatically raise and lower to block the sun.

The facility has a vegetated roof populated with native, low-water-use plants; low-flow toilets, a rainwater harvesting system, and a graywater reuse system all cut down on water consumption. In addition to connecting to light rail and local and regional bus services, the building incorporates ground-floor retail space, offices, a community room, and a bicycle station with showers. To raise public awareness of sustainability, a touchscreen displays the building’s current energy and water use. Local firm Architekton and Otak of Lake Oswego, Oregon, designed the facility to achieve LEED Platinum certification, which is pending.

9. Terry Thomas

Seattle, Washington

Seattle rarely gets uncomfortably warm in the summer, so local architecture firm Weber Thompson designed the four-story Terry Thomas office building to do without air conditioning entirely. Automatic exterior louvers governed by thermostats and carbon dioxide sensors control the flow of air through operable windows, while an open-air central courtyard acts as a chimney, expelling warm air. Exterior sunshades, both automated and fixed, and a reflective roof control solar heat gain; on the east and west facades, custom-made glass sunshades mitigate heat gain while still letting in light.

High ceilings and shallow floor plates enhance natural ventilation and daylight penetration. A hydronic heating system keeps interiors warm in colder months and enables individual temperature control. To handle the rainy climate, a stormwater recovery system slows the rate of runoff into the city’s stormwater system. For the structure, the designers specified recycled steel, aluminum, and fly ash concrete. Completed in 2008, the Terry Thomas received a LEED Gold certification.

10. Watsonville Area Water Operations Center

Watsonville, California

The Watsonville Area Water Operations Center supports a project that treats and recycles wastewater for local farmers to use in irrigation, helping keep saltwater out of the overextended coastal aquifer. The city sought a design for the facility that would conserve water and help educate the public about water use.

With administrative offices, a water quality laboratory, and education space, the 16,000-square-foot (1,500-sq-m) facility channels stormwater down rain chains into swales that filter the water before returning it to the ground. The radiant heating and cooling system circulates water through underfloor tubing. Native, drought-tolerant landscaping and a tiled water feature both use recycled water—and go without when it is not available. Low-flow plumbing fixtures and reclaimed-water dual-flush toilets further conserve resources. Other sustainable strategies include natural ventilation, high-efficiency mechanical equipment, and rooftop solar panels. WRNS Studio of San Francisco designed the LEED Platinum facility, which was completed in 2009.