Authored by Julia Africa, Mary Burkholder, Lisa Clark, Cristina Greavu, Piers MacNaughton, and Paul Mellblom

As built environment professionals, our decisions and actions have significant impacts on the lives of others. In recognition of our responsibility to support conditions that improve the health, environmental quality, economic vitality, and social equity of communities, a subset of Urban Land Institute members, under the auspices of the ULI Health Leaders Network (HLN), has generated a position statement—“Commitment to Health and Equity in the Built Environment”—to affirm health and equity as core values of our work.

We invite all ULI members and nonmembers alike to join our effort by signing onto this commitment.

Context

Health and equity are inseparable. Access to a healthy environment is a human right. While the built environment influences health across populations, unsafe and unhealthy conditions disproportionately affect vulnerable groups that have been subject to longstanding societal inequities. For reference, ULI uses the following commonly accepted definitions of health and equity:

- Health is “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” (World Health Organization)

- Equity is “just and fair inclusion into a society in which all can participate, prosper, and reach their full ” (PolicyLink)

Further, “[h]ealth equity is achieved when every person has the opportunity to ‘attain his or her full health potential’ and no one is ‘disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially determined circumstances.’” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

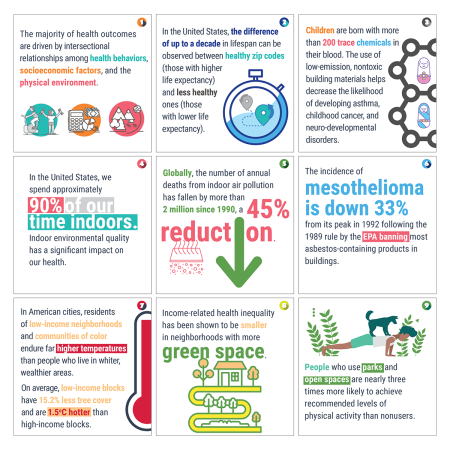

Health inequity historically has occurred in part due to policies and practices involving the built environment that are structured on race, socioeconomic status, and other manners of segregating humanity. This has resulted in disparities in life expectancy, food access, air and water quality, housing affordability, mental health, social well-being, and much more (see graphic). Yet, the built environment can shape health and social equity outcomes for the better.

In order to address the causes of this inequity and achieve health and equity through the built environment, the commitment laid out in the position statement aims to provide a framework that can guide local, regional, and global change.

Commitment

The “Commitment to Health and Equity in the Built Environment” reads as follows:

We the undersigned share the capacity and responsibility to prioritize health outcomes through our work. Collectively, we will:

- Provide affordable and accessible housing, support services, health care, transportation, parks, and education;

- Provide access to high-quality air, water, and nutrition;

- Improve mental health (through stress prevention and reduction, a sense of safety, );

- Promote social well-being (social connections, community cohesion, a sense of belonging);

- Encourage healthy behaviors such as physical activity (active living, walking, exercise);

- Protect or restore site-based ecologies (biodiversity and habitat, water and waste management, access to light, and sound pollution); and

- Realize environmental comfort (thermal, acoustic, visual, physical).

By acting on this commitment we will do our part to repair longstanding inequities that exist in our communities. Through our work, we will:

- Recognize the capital value of a healthy environment in the marketplace and make the case for the cost of inaction;

- Set clear and achievable health and social equity goals for each project in partnership with the communities with which we are working;

- Hold ourselves and our teams accountable for the health and social equity outcomes of our work;

- Employ evidence-based strategies and best practices to achieve these health goals;

- Partner with community stakeholders, health researchers, and clinicians as needed to improve our understanding of and dialogue with the lived experiences of a given community;

- Proactively identify unintended health impacts of our work and commit to rectifying shortcomings where they are found;

- Understand outcomes by tracking project and organizational performance against these goals;

- Continuously expand our collective knowledge base by engaging in research initiatives and collaborative partnerships and by sharing case studies in support of this work;

- Advocate for health and social equity in conversations about development and land use; and

- Bring the health and social equity lens to all ULI initiatives in which we participate.

To act on this commitment most effectively, we must understand and elevate the work of those already engaged in the communities we seek to work with, including community members, public agencies and institutions, not-for-profit organizations, and other professionals.

We will seek to build partnerships within and outside the ULI network that help promote, lead, and champion our goals and our commitment to health and social equity in our communities.

Through the work outlined above, we are committed to the Institute’s mission of shaping the future of the built environment for transformative impact in communities worldwide.

Join us! Sign onto the commitment by following this link.

Health Leader Signatories

The following ULI Health Leaders Network participants have signed on to this commitment:

| Julia Africa | Pete Fritz | Oby Nwabuzor |

| Tim Alcott | Kristen Fulmer | Erin Patterson |

| Ina Anderson | Kathryn Gardow | Cory Paul |

| Eddie Arslanian | Lance Gilliam | ShoMari Payne |

| Bernadette Austin | Arathi Gowda | Melony Pederson |

| Ramune Bartuskaite | Cristina Greavu | Dominic Ramos-Ruiz |

| Stephanie Becker | Celena Green | Paula Reeves |

| Maggie Beckley | Beatriz Guerrero Auna | Dr. Lena Reiss |

| Michael Bloom | Chloe Gurin-Sands | Beth Resetco |

| Natasha Brand | Philip Hart | Soraiya Salemohamed |

| Lindsay Brereton | Ed Hernandez | Stephen Samuels |

| Jeri Brittin | Roger Herzog | Yogesh A. Saoji |

| J. Keith Brown | Hannah Hobbs | Charles Noel Schilke |

| Melanie Brown | Eric Hoke | Treasure Sheppard |

| Monique Brown | Lori Holleran | Melani Smith |

| Mary Burkholder | Rebecca Hollister | Peter B. Smith |

| Amanda Burnham | Kenneth Johnson | Ashley Disher Spinks |

| Hafsa Burt | Saranya Kanagaraj | Berjit Takhar |

| Rex Cabaniss | Michael King | Richard Taylor |

| Rogean Cadieux-Smith | Todd Kohli | Yann Taylor |

| Ryan P. Cambridge | Doug Lamson | Laura Thomas |

| Diane Caslow | Stuart Levin | Ivy R. Thompson |

| Ben Cave | Lida Lewis | Meg Thorley |

| Michael Chang | Brian Lomel | Eime Tobari |

| Patti Clare | Christina D. Long | Laura Unrein |

| Lisa K. Clark | Piers MacNaughton | Ayako Utsumi |

| Michele Crawford | John Macomber | Frans van Vuure |

| Lisa Cutshaw | Bill Mahar | Andrew Watkins |

| Sonia Deal | J. Timothy McCarthy II | Sarah Welton |

| Joe Duffy | Paul Mellblom | Marja Williams |

| Jim Durrett | Kathrine J. Morris | Jane Futrell Winslow |

| TeMaya Eatmon | Michelle M. Morrison | Debra Wyatte |

| Jessica Elliott | James Neville | Anupam Yog |

| Jaime Fearer | Luis Nieves-Ruiz | Bryan Zundel |

To learn more about this initiative, as well as the tools and strategies at your disposal for meeting this commitment, contact [email protected].

References

Resources that informed development of this position statement include the following:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, “Health Equity,” cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm.

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building, 9foundations.forhealth.org/.

- International Living Future Institute, Our Common Living Future: 2022–2024 Strategic Plan, https://living-future.org/.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “Social Determinants of Health,” rwjf.org/en/our-focus-areas/topics/social-determinants-of-health.html.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development, “Do you know all 17 SDGs?” un.org/goals.

- Urban Land Institute, Building Healthy Places Toolkit: Strategies for Enhancing Health in the Built Environment, 2015, uli.org/wp-content/uploads/ULI-Documents/Building-Healthy-Places-Toolkit.pdf.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, “Healthy People 2023: Building a Healthier Future for All,” health.gov/healthypeople.

- S. Green Building Council, “LEED and Human Health,” www.usgbc.org/about/programs/leed-human-health.

- World Green Building Council, “Health & Well-Being Framework,” worldgbc.org/health-framework.

Infographic

1 J. Michael McGinnis, Pamela Williams-Russo, and James R. Knickman, “The Case For More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion,” Health Affairs, March/April, 2002, .

2 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “Life Expectancy: Could where you live influence how long you live?” www.rwjf.org/en/library/interactives/whereyouliveaffectshowlongyoulive.html.

3 Environmental Working Group, “Body Burden: The Pollution in Newborns,” July 14, 2005, ; Amy Cadora, “How to Help Protect Our Smallest Bundles from Body Burden,” Norwex Movement, October 19, 2017, www.norwexmovement.com/protect-smallest-bundles/.

4 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Report to Congress on Indoor Air Quality, Volume 2, 1989, www.epa.gov/report-environment/indoor-air-quality#note1.

5 Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Indoor Air Pollution,” Our World in Data, ourworldindata.org/indoor-air-pollution#death-rates-have-declined-in-almost-all-countries-in-the-world.

6 Asbestos.com, “Mesothelioma Incidence and Trends,” www.asbestos.com/mesothelioma/incidence/.

7 Susanne Amelie Benz and Jennifer Anne Burney, “Earth’s Future,” AGU, agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2021EF002016; Robert I. McDonald et al., “The tree cover and temperature disparity in US urbanized areas,” PLOS One, journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0249715.

8 Richard Mitchell and Frank Popham, “Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities,” National Center for Biotechnology Information, November 8, 2008, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18994663/. Green space is defined as “open, undeveloped land with natural vegetation” and includes, for example, parks, forests, playing fields and river corridors.”

9 B. Giles-Corti et al., “Increasing Walking: How Important is Distance to, Attractiveness, and Size of Public Open Space?” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2005, 28:169-176.