Although video conferencing and other technological innovation has made it possible for economic activities to be dispersed, differences in growth rates, jobs, and incomes have increased, in recent decades, as regions in the Northwest and Midwest have lost population and regions in the South and West have experienced population, employment, and income growth. The negative effects of housing price increases in growing regions serve as a constraint to domestic migration and economic opportunities, especially for lower-skilled workers. In the long run, unaffordable housing prices contribute to unequal regional development and worsening income disparities. Job-rich regions need to encourage housing production.

Regional population shifts

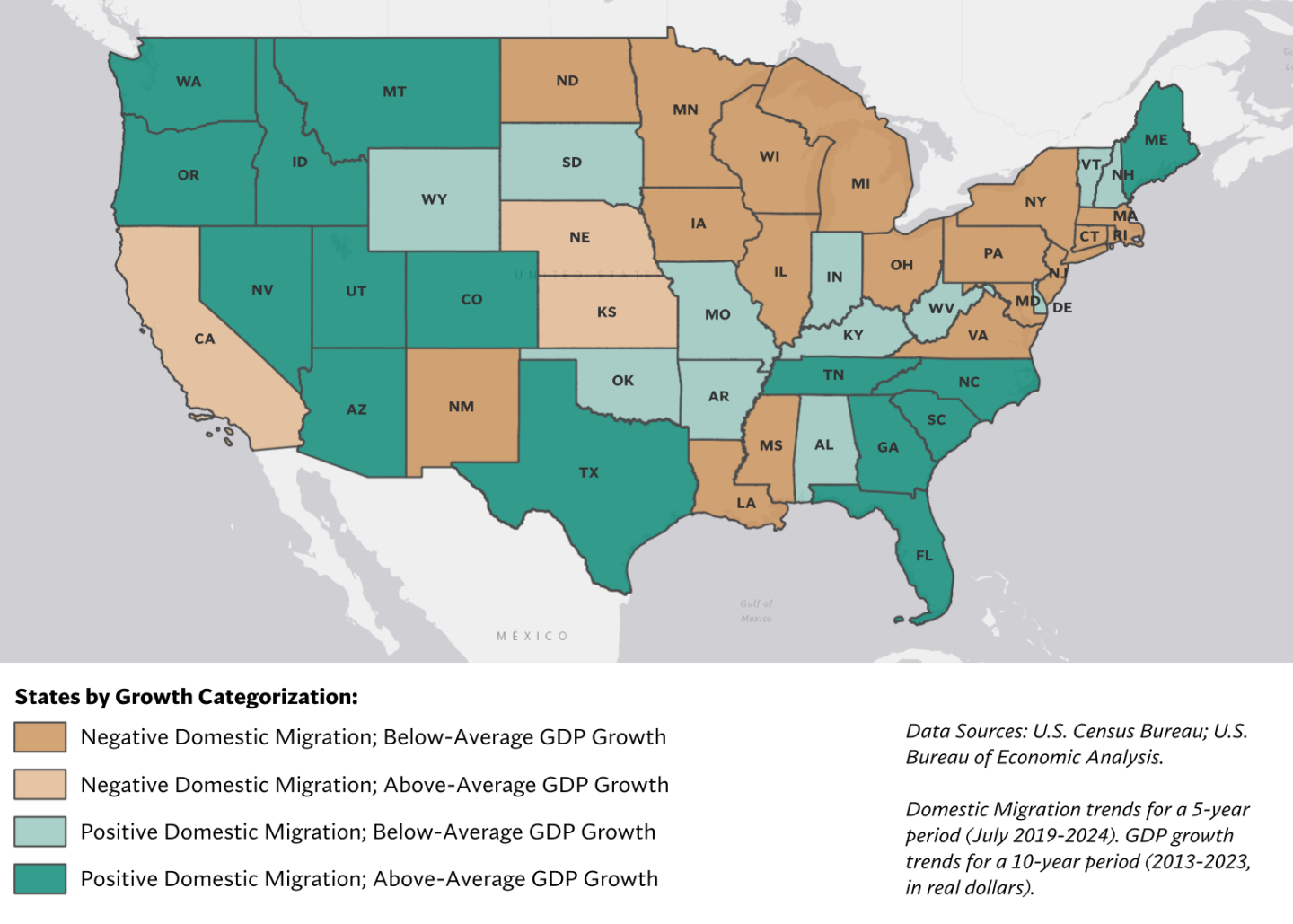

From July 2019 through July 2024, the population of the South increased by nearly 3.2 million people due to domestic migrants, while approximately 702,000 people moved out of the Midwest (mostly from Illinois, with almost 509,000 leaving the state), and approximately 1.5 million people moved out of the Northeast (mostly from New York, from which a million-plus left).

Most of the absolute growth in domestic migrants since 2019 has occurred along the Atlantic coast, with Florida and the Carolinas leading the way. The Southern states that gained the most domestic migrants between July 2019 and July 2024 include: Florida (nearly 985,000); Texas (more than 856,000); North Carolina (more than 454,000); South Carolina (nearly 354,000); and Tennessee (nearly 300,000).

As a percentage of population, the comparatively small Mountain West states have experienced the highest overall rates of domestic migration. Positive domestic migration across states including Idaho, Montana, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado has expanded the Mountain West subregional population by about 3 percent—the highest share of growth of any U.S. Census Bureau division since the 2020 Census. Much of this growth has been the direct result of households leaving nearby California.

Unequal development has resulted in some places becoming vastly poorer and other places vastly better off. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, income inequality rose more than 40 percent between 1980 and 2021.[1] The increase in income inequality reflects how economic activity has become increasingly concentrated rather than dispersed.

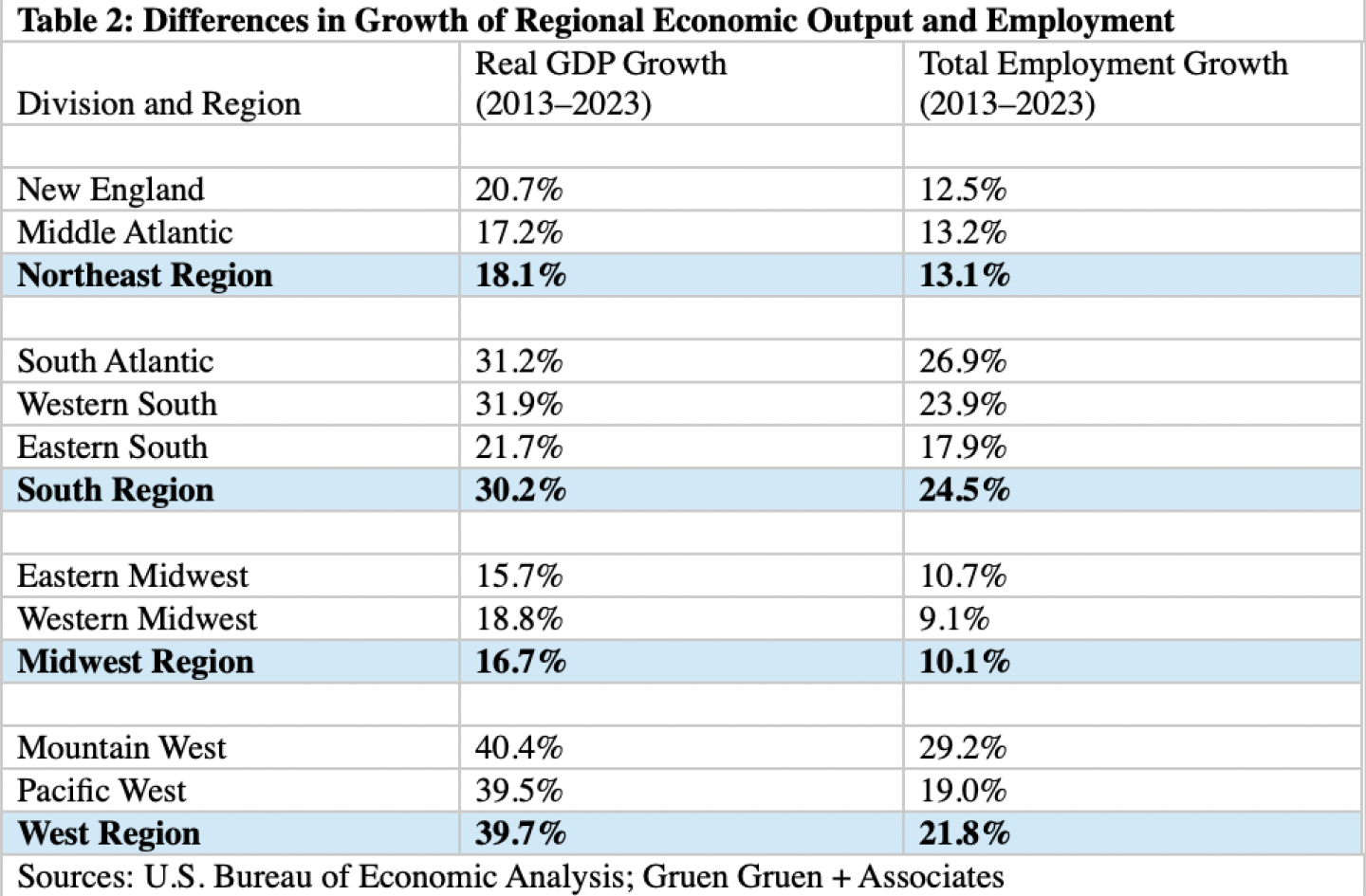

State and regional contributions to national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth have reflected the growth in income disparities and domestic migration patterns. Economic output and employment in high growth “magnet” regions such as the South Atlantic or Mountain West have increased at two to three times the growth rates experienced in parts of the Midwest. Real GDP in the Mountain West and South Atlantic states grew by 40.4 percent and 31.2 percent, respectively, from 2013 to 2023. Total employment in each region grew by 27 to 28 percent over just 10 years.

Except for Maine, all states that experienced positive domestic migration and above-average GDP growth are in the West or South regions. Conversely, apart from the historically poorer states of New Mexico, Mississippi, and Louisiana, states that experienced domestic out-migration and below-average GDP growth are all located in the Midwest and Northeast.

Although the large West region has experienced domestic out-migration in the aggregate—primarily due to exorbitantly high costs in such places as San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and, to a lesser extent, Hawaii—it remains an economic powerhouse, boasting the highest real GDP growth over the past decade. Led by California, which by itself is still the fourth-largest economy in the world, just five Western states (California plus Washington, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah—the other four largest economies in the West) continue to grow rapidly and now account for nearly one quarter of all U.S. gross domestic product.

From 2013 through 2023, economies in only 11 states grew at rates exceeding three percent annually. These states were exclusively in the West and South regions, including annual real GDP growth rates ranging from 3.1 to 4.5 percent.

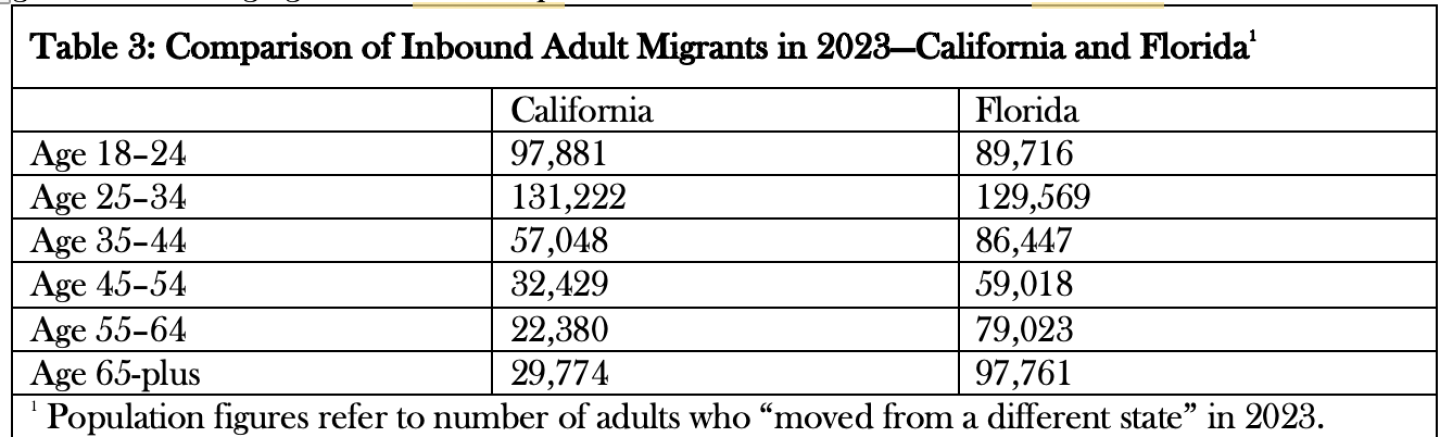

California continues to attract more young adults (ages 18–34) than does Florida, and the number of inbound domestic migrants in their prime working years (ages 25–54) were reasonably similar between the two states, according to 2023 estimates. The largest discrepancies in migration patterns become much more apparent with the older-age cohorts. Some of the net gains or losses among California, Florida, and other retirement-friendly Southern states can be explained by the movements and mobility of older-age adults.

Natural amenities

Differences in natural amenities (such as nice weather) and developed ones (such as art museums, restaurants, and Golden Gate Park in San Francisco or Central Park in New York), plus differences in productivity (which is influenced by physical infrastructure, such as ports and airports, as well as by the skill levels of labor, the size of the labor market, the scale of entrepreneurs present, and the composition of the economic base) lead to differences in the jobs and incomes that regions can generate.

As segments of the population have become wealthier with higher incomes, the willingness of households to pay for locations with natural amenities such as beaches and pleasant weather in such places as Florida and the Carolinas, for example, has increased. In some cases, households accept less income or having to spend a higher share of income on housing to live in amenity-laden locations.

Restrictive land-use policies

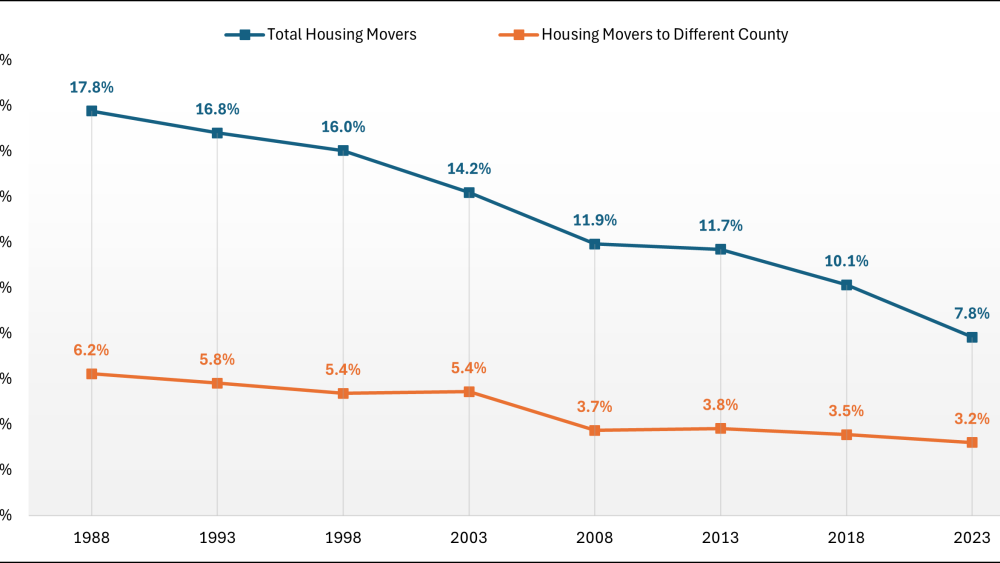

Figure 1 shows a persistent decline in mobility in the United States. Since the late 1980s, mobility rates have declined consistently and precipitously, from about 18 percent in 1988 to below 8 percent as of 2023. Household moves to a different county have declined by almost one half to 3.2 percent in 2023, from 6.2 percent in 1988. Households moving from one location to another location in a county have declined from about 12 percent in 1988 to below 5 percent in 2023.

Figure 1: Annual Geographic Mobility Rates in the United States, 1988–2023

High housing prices cause resources to be misallocated. The nation’s most productive and job-rich cities, through stringent land use regulatory restrictions on new housing supply, have effectively limited the numbers and types of workers who have access to such economic opportunities. As described in an article in 2018 by University of Minnesota economists Kyle F. Herkenhoff, Lee E. Ohanian, and Edward C. Prescott, and previously by Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, low housing production relative to demand slows real GDP growth because restrictions on supply raise housing prices and discourage people, especially lower-income households, from moving to regions with higher productivity and higher wages.

A simple way to illustrate what these economists found is to consider that New York City experiences faster than typical productivity and wage growth, but few housing units are constructed there, so residents expend some—or much—of their higher wages on higher housing costs or rent. In Buffalo, higher- and lower-skilled workers learn of job opportunities in New York City that would pay more than they earn in Buffalo. It would not be unusual, however, if only the higher-skilled workers conclude that moving for a job in New York City would be beneficial. As a result, incomes grow faster in New York City than in Buffalo.

Indeed, in the early 1980s, the incomes of households in the Buffalo and New York City metros were reasonably comparable (differing by about 25 percent), but the income growth of Buffalo households has lagged the income growth of New York City households. As of 2023 estimates, the average per capita incomes in New York City and Buffalo were $91,000 and $61,000 respectively.

Policy action recommendations

Public investment in convention centers, stadiums, and other frequently popular megaprojects in cities trying to increase economic opportunities, jobs, and incomes will not make up for deficiencies in the prerequisites for placed-base success. Cities can, however, appropriately make prudently sized public investments in amenities and services to help attract and retain skilled residents and companies that depend upon such talent. Authentic, sustainable amenities and services will appeal to tourists, too. Omaha, Nebraska has, for example, added a concert venue, a science center, and enhanced parks in its downtown that have contributed to the area’s recovery from the pandemic through increased weekend and evening visitation and through increased residents living in that area.

Municipalities can encourage needed increases in housing production by:

- Developing and implementing plans to fund needed infrastructure, including road, storm drainage, sewer, and transport networks to serve households and the labor innovative companies need

- Removing regulatory impediments to compact, mixed-use development, including residential uses in and near employment centers such as business parks

- Zoning more land for higher-density housing. Higher minimum suburban densities, from 14 units per acre and as many as several hundred units per acre in urban locations, will help keep land prices from continuing to escalate excessively

- Formally recognizing housing as a critical component of local and regional economic development policy. Economic developers typically attend land use hearings for nonresidential uses but do not often do so for proposed residential developments. Economic developers and nonresidential developers should support housing developments and encourage local land use regulators to zone more land for relatively higher-density housing

- Expediting review and approval processes for all types of housing and, especially, for affordable housing

- Lowering impact fees when feasible

The negative effects of housing price increases in growing regions serve as a constraint to domestic migration and economic opportunities, especially for lower-skilled workers. In the long run, unaffordable housing prices contribute to unequal regional development and worsening income disparities.

Although not a panacea, improving the amenity and services base can be a critical part of place-based economic development strategies to retain and attract household and job growth in communities outside areas where growth has been concentrated.