By filling vacant lots and replacing underused or derelict structures, infill development can enhance street life and help curb sprawl. However, facing relatively higher land costs in more densely built-up areas, developers must do more with less space. Zoning rules, height limits, oddly shaped sites, the proximity of adjacent buildings and infrastructure, and other constraints require creative design and engineering strategies.

All completed in the past five years, the following ten projects employ various tactics to circumvent the limitations of their sites. Some cantilever, some compress, some interlock, some zigzag, and some undulate.

1. 1112 Locust Street Addition

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

One method of getting the most out of the built environment is simply to expand existing structures. In Philadelphia’s Washington Square West neighborhood, local architecture firm Rasmussen/Su designed a sliver of an addition to a 19th-century rowhouse on a site only 9.5 feet (3 m) wide. The three-story insertion adds 900 square feet (84 sq m), enlarging the existing ground-floor café while turning the studio units above into one-bedroom apartments.

The street-facing facade is clad in Corten steel panels, with openings that recall those of the original masonry structure; the facade’s laser-cut pattern of ginkgo leaves is designed to reference the greenery of the adjacent community garden. The side and rear elevations are faced with silver-black brick. Although the building clearly reads as contemporary architecture, its scale, composition, and materials were chosen to complement the existing structure, which was crucial to winning approvals. The project was completed in 2010 for local owner Gibbs Connors.

2. Art Stable

Seattle, Washington

As anyone who has tried to haul a sofa up four flights of stairs can attest, urban multifamily housing can be a challenge for those moving heavy objects. In Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood, on a 0.1-acre (0.04 ha) site that once housed a stable, local firm Olson Kundig Architects has solved that problem at a seven-story, 25,600-square-foot (2,400 sq m) mixed-use building sandwiched between two other structures. Completed in 2010 for local developer Point32, the building comes equipped with an 80-foot-tall (24 m) hinge topped by a davit crane, rising to the top of the alley-facing facade.

Each unit has a large hand-cranked door on this hinge, enabling residents to hoist works of art or furniture from street level. On the street facade, smaller hinged windows enable natural cross-ventilation. Stacked above ground-floor retail space and second-level parking, the five units, one per floor, are zoned for residential or commercial use. The exterior palette of concrete, glass, and steel references the neighborhood’s industrial heritage.

3. The Domenech

Brooklyn, New York

For a seven-story, 63,000-square-foot (5,900 sq m) apartment building in Brooklyn, earmarked for homeless and low-income seniors, New York City–based firm Jonathan Kirschenfeld Architect P.C. decided to cope with the deep, narrow site by forgoing double-loaded corridors. To save room, Kirschenfeld configured the apartments in a U shape, reached via single-loaded corridors at the side lot lines. Placement of bearing walls parallel to the street enabled the walls facing the mews-like court to be skinned with translucent Kalwall panels, which have the virtues of being extremely thin, offering high thermal efficiency, and increasing natural light in the units.

The seventh story is set back from the street, leaving room for a vegetated roof terrace. Use of high-efficiency mechanical equipment and light fixtures, recycled and recyclable materials, and low-flow plumbing helps the project target a Gold rating under the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program. Completed in 2011 for New York City–based nonprofit housing developer Common Ground, the building has 72 units plus support services and received funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

4. Evelyn Grace Academy

London, U.K.

On a 3.5-acre (1.4 ha) site that is one-quarter the typical size for a secondary school in London, the Evelyn Grace Academy packs in two middle schools and two upper schools, with 1,200 students in all. The academy is surrounded by a maintenance depot and a civic data storage building. London-based Zaha Hadid Architects laid the academy building out diagonally across the site, tucking one floor into a partially hidden podium to reduce the visual impact. A running track bisects the building, helping break up its apparent size; playing fields provide a further buffer.

The 115,658-square-foot (10,744 sq m) academy’s massing expresses each school individually, and each has its own entrance, staircase, and courtyard. Extensive glazing in classrooms and in central assembly areas helps bring a sense of spaciousness to the efficiently sized interiors. Completed in 2010, the academy is owned and operated by the charity ARK (Absolute Return for Kids).

5. HL23

New York, New York

The conversion of New York City’s disused, elevated High Line rail track into a linear public park created prime space for luxury residences. Local developer Alf Naman gave Neil M. Denari Architects of Los Angeles a particularly challenging site: only 40 by 99 feet (12 by 30 m), squeezed between the High Line and another high rise, with zoning rules limiting its height to less than 165 feet (50 m).

Denari worked with the city to obtain seven zoning variances, resulting in an unusual shape for the building, which bulges as it rises; upper floors are as much as 40 percent larger than the street-level footprint. The diagonal braces necessary for this balancing act are expressed inside the curtain wall and echoed by white ceramic frit on the glazed facade, softening the angles. The 14-story, 39,200-square-foot (3,600 sq m) HL23 contains 11 condominium units. Motorized shades give residents privacy without disrupting the facades’ smooth lines. The building was completed in 2011.

6. Lunder Building

Boston, Massachusetts

Demand for clinical services at Massachusetts General Hospital far outstripped the facility’s capacity, so in 2004 the institution opened the Yawkey Center for Outpatient Care and last year opened the second phase: the 535,000-square-foot (49,700 sq m) Lunder Building, which has emergency and radiation oncology departments, procedural programs, and 150 single-patient rooms.

To squeeze the building onto the dense hospital campus, the Boston office of NBBJ used building information modeling to manage the site’s complex requirements. These included linkages to five existing buildings via multiple bridges and walkways, completing an indoor pedestrian pathway that extends the length of the campus. Four of the floors are below ground, ten above. To accomodate more single-patient rooms, the design team broke the floor plate into two interlocking C-shaped groups of patient rooms, connected by a circulation spine. The strategy also cut travel distances for staff.

7. Penn Street Lofts

Quincy, Massachusetts

On the corner of a tree-lined neighborhood of single-family homes in Quincy, Massachusetts, Touchstone Properties LLC of Braintree, Massachusetts, tore down an old industrial building to make way for multifamily housing. However, zoning laws required that the new construction exactly follow the footprint of the previous foundation wall and rise no higher than the previous structure’s peak. Merge Architects of Boston maximized the resulting building envelope to create a box, then incorporated six condominiums, interlocking the multistory units in jigsaw-puzzle fashion. This strategy resulted in varied window locations, avoiding monotony on the exterior.

To give residents private outdoor space, the designers scooped out recessed balconies from the building’s volume. Each unit has its own entry and private indoor garage. Red cedar clapboard siding helps the four-story, 15,000-square-foot (1,400 sq m) building fit in with its older residential neighbors. Penn Street Lofts was completed in 2010 for a construction cost of $100 per square foot.

8. Ray and Dagmar Dolby Regeneration Medicine Building

San Francisco, California

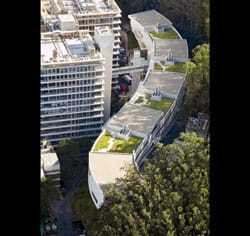

Along the steeply sloping flank of San Francisco’s Mount Sutro, a thin slice of land remained as the only piece available for development at the Parnassus Campus of the University of California at San Francisco. In creating the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Regeneration Medicine Building, dedicated to stem cell research, the design team could have vertically stacked the program in a tower. Instead, to better support collaboration among researchers and scientists, the designers structured the 68,500-square-foot (6,400 sq m) building as a 660-foot-long (200 m) sinuous structure that follows the site’s topography, with four open labs, each interspersed with offices and lounges. Terraced grass roofs provide additional places for informal gathering.

Navigating the 60-degree slope in such a seismically sensitive area required placing the building on a steel-framed platform supported by base isolators on concrete piers. The only access is through a glass-enclosed bridge connected to the ninth floor of an existing building. Rafael Viñoly Architects of New York City was design architect; SmithGroup’s San Francisco office was the architect of record. The building was completed in 2011.

9. St. Thomas the Apostle School

Los Angeles, California

St. Thomas the Apostle School, a K–8 parochial school in Los Angeles, operated out of a small, 80-year-old building strained by heavy community and church use. Expansion was restricted by the size of the 1.63-acre (0.7 ha) site. Griffin Enright Architects of Culver City, California, renovated the 18,900-square-foot (1,800 sq m) building and linked it to a new 18,815-square-foot (1,748 sq m) multipurpose building via bridges. Many elements had to serve double duty. The new subterranean parking structure accommodates 100 cars and supports a playground on its roof. A new driveway encircles the site, acting as the required fire lane and accommodating a new drop-off on site to relieve traffic congestion.

The main pedestrian path leads to a large porch at the entrance, which serves as an outdoor lunchroom and stage for performances. A landscaped forecourt provides additional playground space on schooldays and extra parking space on weekends. The addition was completed in 2010.

10. Target Field

Minneapolis, Minnesota

The Minnesota Twins’ initial plans for a new stadium to be located along the Mississippi River fell through when public financing did not become available. The next choice, 8.5 acres (3.4 ha) of surface parking in downtown Minneapolis’s warehouse district, was unusually small for a professional ball field. In addition, the Kansas City, Missouri, office of architecture firm Populous had to fit a 40,000-square-foot (3,300 sq m) ballpark on a spot constrained by a municipal garbage incinerator, Interstate 394, two elevated roadways, train tracks, parking garages, and an underground creek.

The design team negotiated with a number of civic entities to eke out space, and even persuaded the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway to move a rail line 75 feet (23 m). Portions of the stadium, such as the outfield grandstand seating and a club, cantilever over transit lines, and a bridge spanning the interstate highway serves as the main entrance and a gathering plaza. The venue incorporates a station serving light rail and commuter rail. The Twins played their first game at Target Field in April 2010.