A public/private partnership in Surrey, British Columbia, builds a mixed-use city center near Vancouver.

One might not expect to find a 52-story tower at the heart of a suburban city 20 miles (32 km) southeast of downtown Vancouver, British Columbia, a city more than three times greater in density. But the city of Surrey’s population is expected to exceed Vancouver’s within the decade. The tower alone, called 3 Civic Plaza (3CP), houses five separate uses: 349 condominium units, a 144-hotel-unit Marriott Autograph Collection Hotel, 53,000 square feet (5,000 sq m) of offices, and classrooms for Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU) and its urban business and health science programs. The project also comprises 14,000 square feet (1,300 sq m) of retail and restaurant space above a 407-space underground parking garage and is built on a site smaller than 0.8 acre (0.3 ha) that yields a density of 621 units per acre (1,553 units per ha).

Dense, Mixed-Use City Center

The inverted angled walls of the library frame the view across the Civic Plaza to the Civic Hotel. The five-floor volume of the Kwantlen Polytechnic University urban campus cantilevers over the fourth-floor roof deck that contains the hotel pool and fitness center, while the angled facade of the condo rises above. The slender, 20-story hotel tower is used like a flying buttress in Gothic cathedrals to add lateral stability to the condominium tower. (Ed White Photographics)

The Civic Plaza site is a five-acre (2 ha) block that comprises a mix of uses—the 210,000-square-foot (20,000 sq m) Surrey City Hall on the north side of a 67,000-square-foot (6,000 sq m) civic plaza above the 800-space Surrey City Hall parkade; an 82,000-square-foot (7,600 sq m) inverted polyhedron that is the Surrey City Centre Library on the west side; and 3CP on the east side of the Civic Plaza site.

3CP is 1,000 feet (300 m) north of the 390-foot-tall (120 m) Central City Tower, the mixed-use redevelopment of the former Surrey Place Mall, which now houses offices, shops, and the urban campus of Simon Fraser University. The taller 3CP is a 537-foot-tall (165 m) campanile, or bell tower, marking the end of the northern axis of the urban heart of Surrey City Centre while Central City Tower marks it southern end.

The Civic Plaza is adjacent to the Surrey Central Station that is the penultimate stop near the end of the elevated SkyTrain Expo Line commuter rail, which was built in 1985 ahead of Expo ’86, a World’s Fair focused on transportation and communication. A bridge built across the Fraser River in 1990 extended the line, and the final, eastward addition was completed in 1994. A trip to downtown Vancouver from Civic Plaza takes 37 minutes.

The Expo Line’s average daily ridership of about 400,000 commuters was a major development incentive to maximize 3CP’s density. However, contractors had to meet the challenge of building a tower only 18 feet (5 m) away from the active elevated rapid transit system with trains rushing by at speeds of up to 55 miles per hour (88 kph).

The large and convenient rapid transit system notwithstanding, a city center still needs adequate parking. Despite its high density and mix of high-traffic public and private uses, with 1,207 parking spaces, Civic Plaza is able to operate successfully at an overall shared-parking ratio of 1.4 parking spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 sq m) or unit. While condominium parking is restricted, people using the hotel, restaurant, retail, and KPU can access the underground parking garage.

Structural Innovation

For several decades, the predominant structural form of high-rises in Vancouver has been the point tower—typically a tall, slender, glass-walled tower built on a small floor plate measuring less than 8,000 square feet (745 sq m) and exceeding 20 stories with fewer than 10 units per floor. A rigid concrete core housing elevators and scissor-elevation staircases gives such structures vertical rigidity and lateral shear strength to resist wind loads.

Although point towers require a higher ratio of more expensive external skin facade area to less expensive internal floor area, typified by conventional slab building shapes with more than double the number of units per floor, Vancouver developers have been able to sell units at higher prices because the point towers create more of the highly marketable corner units and longer views. Vancouver’s view cone ordinances reinforce the use of point towers.

Tall, narrow, exposed end shear walls define the elegant urban character of the slender tower. Inverted guitar pick–shaped windows in the forms are a counterpoint to the full-height glass walls that wrap around their ends. The 3CP tower stands only 18 feet (5 m) away from the elevated rapid SkyTrain transit system, whose trains ferry residents and visitors to downtown Vancouver in 37 minutes. (Ed White Photographics)

When designing the building’s structure, architect Patrick Cotter—now managing partner of the Vancouver office of Portland, Oregon–based Zimmer Gunsul Frasca (ZGF) Architects, but then head of Cotter Architects, the architect of record—said, “We knew we couldn’t use a rigid core design typical of other concrete residential [point] towers . . . [because] . . . that would be a third of our construction budget, and vertical circulation in one core would have eaten up the floor area, making the building very inefficient.”

Besides, unlike the point towers, the development program called for accommodating four kinds of uses with varied floor plate demands and structural bay spacing. So, Cotter explored structural alternatives that would allow for individual expression of the volumes demanded by each of the uses within a structural framework that could support the building and resist wind loads.

Cotter/ZGF and Vancouver-based engineering firm Fast & Epp devised a scheme using strategically placed two-to-4.5-foot-thick (61 to 137 cm) concrete shear walls forming a brace frame to externally support the building. Two 40-foot-long (12 m) shear walls flank the north and south ends of the condominium tower and are visible as the narrow edges of the slender tower. An 80-foot-long (24 m) internal shear wall just west of the bank of four condominium elevators stabilizes the long spine of the building. It connects in a “T” shape to the south end wall and separates the condos from the hotel and its four elevators.

Cotter says, “It cost less than the conventional approach, and the two-foot-thick [0.6 m] frame allowed for individual structural grids for both public and residential areas, as well as for exit stairs.” He continues, “Concrete is the ubiquitous construction material for high-rise projects in metropolitan Vancouver due to the availability of inexpensive aggregate from gravel deposits along B.C.’s Sunshine Coast, a short barge distance away.”

The shear walls were slip-formed with two-story-tall, 40-foot-wide (12 m) forms. Those walls also define the elegant urban character of the slender tower. Inverted guitar pick–shaped windows in the forms are a counterpoint to the full-height glass walls that wrap around their ends.

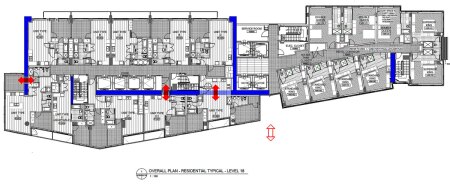

Click above to zoom. Engineers devised a scheme using strategically placed two- to 4.5-foot-thick (61 to 137 cm) concrete shear walls forming a brace frame to externally support the building. Two 40-foot-long (12 m) shear walls flank the north and south ends of the condo tower and are visible as the narrow edges of the slender tower. An 80-foot-long (24 m) internal shear wall just west of the bank of four condominium elevators stabilizes the long spine of the building. It connects in a “T” shape to the south end wall and separates the condos from the hotel and its four elevators. (ZGF/Cotter Architects)

Varied Floor Plate Design

Freed from structural constraints, ZGF was able to shape the floor plates to best accommodate the different development programs. The condo tower is a 130-foot-long (40 m) building that measures only 65 feet (20 m) wide at its widest point and which tapers to about 10 feet (3 m) toward the ends, enabling varied unit sizes. However, there are still only 10 units per floor, similar to the point towers, because the building’s height allows the condominium floors to rise 40 stories over the larger mass of the KPU campus. The larger units face Vancouver to the west, and the smaller units face the North Cascades mountains to the east.

The unit mix is five two-story penthouses, four three-bedroom units, 12 two-bedroom-plus-den units, 91 two-bedroom units, 35 one-bedroom-plus-den units, and 202 one-bedroom units. The design also facilitated shallower units where floor-to-ceiling glass walls bring daylight deep into the units. Recessed balconies enhance spatial livability while permitting smaller units to be more affordable. Condo sale prices started at C$279,900 in 2018 or roughly C$525 per square foot for a small one-bedroom, significantly lower than the C$1,000 to C$3,000 per square foot rate typical in downtown Vancouver, making these attractive to the commuter market.

Tower as Flying Buttress

The design decision to separate the use components enabled the hotel to be narrower—35 feet (11 m) wide—at its end. But the 20-story slender tower is used like a flying buttress in Gothic cathedrals to give further lateral stability to the condominium tower. Angled at the same southwest orientation as the condos, there are nine units per floor, including six king and three double-queen rooms.

The entire fourth floor of the building houses the 16,000-square-foot (1,500 sq m) fitness center and pool, which is accessible to condominium residents and hotel guests. The second and third floors house the hotel’s ballrooms, board room, and meeting rooms.

The ground floor consists of a grand lobby serving the hotel and condominium, with a three-story glass wall facing Civic Plaza. It also has the hotel restaurant of about 3,800 square feet (350 sq m), and retail shops.

Sustainability Strategies

When four uses are contained in a single building—even one divided by shear walls—there is a greater need for the ability to capture, recapture, and transfer energy to where it is needed at different times among the varied uses. The mechanical system is based on a hydronic fluid loop throughout the building. From this loop, the building’s mechanical systems can remove or deposit heat for each space, and available energy can be reused elsewhere. For example, the office floors would mostly be in cooling mode during the day. The heat rejected from that area can then be used to heat the pool or help heat water in the residential tower.

The mix of uses in the building is enhanced by connection to other uses in the city of Surrey’s District Energy Utility in the city center. Heat is drawn from various sources, including a geo-exchange field next door under the City Hall parkade, off-site boilers, and even waste heat from other buildings on the District Energy loop.

The lobby and ballrooms use displacement ventilation instead of conventional top-down air conditioning. Large-volume, low-velocity supply air chilled to a few degrees below ambient room temperature is introduced at the floor area. Occupants’ body heat draws a column of that fresh air up to a plenum (a space between the ceiling and the structural floor above) in the ceiling where the heat is recaptured and fouled air is extracted. This strategy is more efficient and more comfortable than the conventional method of blowing cold air from diffusers in the ceiling.

Architects and engineers had to ameliorate the solar overheating gain of the building’s western–eastern building orientation. They devised a passive heat-rejection system through a low-tech dual-skin facade. It intercepts the hot rays of the sun before they overload the interior mechanical system. A specially coated roller blind keeps solar radiation in the cavity behind the glass, and operable vents at the top and bottom of the windows draw in fresh air at the bottom of the cavity and expel air at the top. By using one-tenth the usual number of fans, this stack effect airflow system saves energy and money.

From the hotel, one can see the contrast of the high-density urban Surrey City Centre just 500 feet (150 m) away from the six-lane, divided conventional suburban commercial strip that is King George’s Boulevard flanked by mostly single-story supermarkets, drugstores, and similar structures surrounded by surface parking lots and, beyond them, garden apartments and single-family houses.

Public/Private Partnerships

The Surrey City Centre concept emanated from a 2008 decision to relocate City Hall to a more urban location in North Surrey on property immediately beside the Expo Line SkyTrain guideway and across the street from Surrey Central Station. The local transit authority had a preexisting entitlement on the property that gave it the right to review and approve the 3CP design.

“Parking and access agreements with Surrey City Hall were key to the success of the project,” Cotter says. An agreement provided that all vehicle access be from the City Hall parking entrances to the underground access to the Civic Plaza parkade, thereby minimizing vehicular activity for the city center and increasing its efficiency.

The Surrey City Development Corporation (SCDC), a for-profit public development corporation incorporated in 2007 separate from the city of Surrey, is governed by an independent board of directors and undertakes development projects, often in partnership with the private sector, that the private sector typically would not take on alone, and it has paid an annual dividend to the city of Surrey since 2013. The SCDC purchased the 3CP site in 2012 and held it as a pro-rata equity partner in the project until it sold the property to the Century Group upon completion of the project in 2019.

Century Group, a 60-year-old development, construction, management, and hospitality company based in New Westminster, British Columbia, owns the hotel outright. It manages the Civic Hotel and its Dominion Bar + Kitchen restaurant through a franchise agreement with Marriott under its Autograph Collection brand. The total construction cost of 3CP was C$142 million, while the total development cost was C$205 million.

The five floors of office space were developed as strata-titled office spaces that KPU purchased for its business and health science programs. The term strata is the term favored in British Columbia for what is characterized as a commercial condominium in the United States. When the offices and residential condominiums were sold, Century retained the base floors and hotel.

There is a notable contrast between the high-density urban Surrey City Centre just 500 feet (150 m) away from the six-lane, divided conventional suburban commercial strip that is King George’s Boulevard, flanked by mostly single-story supermarkets, drugstores, and similar structures surrounded by surface parking lots—and beyond them, garden apartments and single-family houses. City planners and developers can observe the transformation of traditional single-use suburban environments to high-density, mixed-use urban ones undertaken by partnerships of city leaders, public development corporations, universities, transit agencies, and private enterprises.

WILLIAM P. MACHT is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University in Oregon and a development consultant. Access past versions of Solution File.