An improving economy, along with an upswing in convention and tourism business, has spawned a boom in hotel development throughout Chicago’s central business district. More than a dozen new hotels have opened over the past year, are under construction, or are undergoing renovation or expansion.

The downtown market currently has about 34,000 hotel rooms, but Nate Sahn, senior managing director and hotel practice leader for the Los Angeles–based brokerage firm CBRE, estimates that in 2016 when projects under construction and planned are completed, hotel room capacity will increase by 15 to 20 percent.

“I think this recovery is going to be steady and long lasting,” Sahn says. “There’s pent-up demand and a lot of money to be placed, invested.” Investment capital is made up of a mix of domestic and foreign money coming out of Europe, the Mideast, and East Asia, he notes. He cites two examples: a German pension fund that has invested in the new JW Marriot that opened in July in the financial district, and Qatari investors who have purchased 75 percent of the new Radisson Blu, which opened in 2011 as part of a mixed-use project.

Sahn also notes that lenders are offering very attractive financing on development deals, so developers now can afford to pursue more speculative projects.

Forces Driving Hotel Development

More than 600 companies moved to Chicago or expanded their operations there in 2012, adding more than 50,000 jobs, according to the city’s annual “World Business Chicago” report. This included an upturn in the manufacturing and high-tech sectors, which significantly increased the flow of business travelers to the city, as well as demand for select-service hotel rooms, notes Greg LaBerge, national director for the Marcus & Millichap brokerage firm’s National Hospitality Group. As opposed to full-service hotels, select- or limited-service hotels provide basic services business travelers require, such as free wi-fi and a business center with computers, printers, and a fax machine.

He cites a turnaround in the auto industry and the emergence of a high-tech incubator in downtown’s Fulton Market–Randolph meatpacking district as primary forces affecting business travel. The authenticity of the old industrial buildings in this northwest downtown district is attracting tech companies, which are repositioning the properties as creative office space—and in the process bringing the district back to life. Google, for example, plans to move its Chicago office into the district’s old Fulton Market Cold Storage building. Previously obsolete industrial buildings also have been converted for use as restaurants and bars.

Hotels are coming to the area, as well. Recently, a joint venture of Chicago-based Shapack Development and AJ Capital Partners began converting an old rubber belt factory into a 40-room SoHo House, a London hotel group brand. In addition, Chicago developer Sterling Bay Cos. is planning a new 150-room hotel on a site adjacent to Google’s new offices, and Chicago developer Mark Hunt has proposed a 12-story, 120-room hotel and Japanese restaurant for New York City–based Nobu Hospitality, which is owned in part by actor Robert De Niro.

City Puts Hotel Developer Wheels in Motion

The city’s increase in group and leisure travel business over the past couple of years is the result of changes in the city’s convention and tourism operations—with some help from strategically focused marketing by Choose Chicago, the city’s convention and tourism bureau.

Don Welsh, president and chief executive officer of Choose Chicago, credits Mayor Rahm Emanuel for supporting quick implementation of three major changes that restored the city’s competitive advantage as a convention market:

- The city’s convention and tourism agencies were collapsed into one new agency, Choose Chicago, responsible for both sectors.

- The city’s convention and tourism budget was increased from $13 million in 2011 to $24 million in 2012 and again to $33 million this year. This enabled Choose Chicago to establish ten foreign marketing offices throughout the Americas (Brazil, Mexico, and Canada), Asia (China and Japan), and Europe (United Kingdom, Brussels, and Germany), and launch regional advertising campaigns that targeted leisure tourists living in major cities within a 300-mile (480 km) radius of Chicago.

- Labor rules at McCormick Place, the city’s convention center, were relaxed and prices for services were more competitively priced after several major convention clients threatened to take their business elsewhere. Previously, exhibitors were required to use union labor to set up and break down exhibition booths, but now they are allowed to do the work themselves. McCormick Place also began to offer free wi-fi and lowered both prices for the use of utilities by convention participants and the markup on food and beverage service.

As a result of these changes, Chicago moved up three notches over the past year to second place—behind only Orlando, Florida, and passing Las Vegas—on the list of the top 50 U.S. meeting destinations based on event bookings, compiled by Cvent, a meetings management company.

Welsh notes that with the resurgence in the city’s meeting business, the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority, which owns McCormick Place and the 1,260-room Hyatt Regency McCormick Place hotel, has announced plans to add a new 1,200-room hotel and a 10,000-seat multipurpose arena there.

Also, the number of tourists visiting Chicago rose by 7 million over two years, from 39.2 million in 2010 to 46.2 million in 2012, according to Choose Chicago’s annual “Hotel Performance Report.” Domestic visits rose 11.2 percent, and leisure travel increased by 6 percent, outperforming average national increases in those categories of 6.7 percent and 5.4 percent, respectively.

John Chikow, president and chief executive officer of the Greater North Michigan Avenue Association (GNMAA), a business improvement organization that promotes retailers on the city’s Magnificent Mile along Michigan Avenue, notes that this shopping district is seeing more foreign shopping tourists than ever, which is helping drive hotel development in the area.

GNMAA sponsors two major retail events that attract regional shoppers—the Magnificent Mile Shop Fest, a 12-day event that begins in late August, and the BMO Harris Bank Magnificent Mile Lights Festival, which takes place the weekend before Thanksgiving. Chikow notes that the Lights Festival is the biggest annual event in Chicago, attracting 1.2 million people in 2012. During this event, the area’s hotel occupancy rate typically soars to 98 percent, he says.

Average hotel occupancy this year has climbed back to the 75 percent high watermark set in 2006, even though the number of hotel rooms has increased by 6,000, according to a recent report by CBRE. Visitors pump $12 billion into the city’s economy each year, providing 120,000 jobs and generating $500 million in tax revenue, notes Welsh.

Emanuel and the Choose Chicago board of directors have set a goal of a total of 50 million visitors by 2020, Welsh notes. Attaining this goal would increase total tourism revenue to $15 billion a year, add 15,000 to 25,000 jobs, and more than double the city’s tax receipts from tourism-related businesses to $1.2 billion.

Plethora of New Hotels Rising

According to Choose Chicago, 1,950 new hotel rooms will come on line this year in the downtown market, and another 2,050 rooms now under construction are expected to be completed by 2015.

About 60 percent of hotel development is in the north Loop/Michigan Avenue area, notes architect Christine Carlyle, a principal and director of planning at Solomon Cordwell Buenz (SCB), an architecture, planning, and interior design firm in the city. This area adjacent to Lake Michigan, known as Chicago’s Gold Coast and home to the Magnificent Mile shopping district, attracts millions of leisure travelers annually thanks to its location.

SCB architect Gary Kohn designed the new Loews mixed-use hotel project on North Park Drive in the north Loop area. Developed by Chicago-based DRW Trading Group and owned and managed by Loews Hotels & Resorts, the project, scheduled to open in 2015, includes a 400-key hotel and 398 luxury apartments. Located in the affluent Streeterville neighborhood, the project is part of a large planned development connecting Chicago’s riverfront and lakefront to North Michigan Avenue.

“This is Loews’s first Chicago hotel, and they looked a while for the right site,” says Kohn. The 52-story project’s contemporary, glassy design takes advantage of views of city lights, the Chicago River, and Lake Michigan.

“This is a very walkable neighborhood with lots of restaurants in the area, and there’s shopping and entertainment across the street, including a bowling alley, movie theater, marketplace, and nightclubs,” Kohn adds. The site also is just a ten-minute walk from the downtown shopping district and lake, he notes.

Designed with hopes of garnering a four star–plus hotel rating, the L-shaped tower is organized to provide guests “a gracious arrival,” he says. The structure’s nearly 1 million square feet (93,000 sq m) of space will consist of a four-story hotel podium with ballrooms, meeting space, two restaurants, a bar, and a large terrace for events, topped by 12 stories of sophisticated hotel rooms, and 36 stories with a combination of apartments and amenities.

Residents will have access to hotel room service, concierge service, and housekeeping services, as well as to multiple roof terraces with outdoor bars and cafés, indoor and outdoor pools, and a fitness club, Kohn notes.

Although the project is not pursuing certification under the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, he says, “the building is designed for high performance and energy efficiency for both lighting and the HVAC [heating, ventilation, and air conditioning] system, has a green roof, and high-performance tinted glass. We spent a lot of time getting that right.”

The Return of a Prerecession Concept

Carlyle observes that the Loews project, which places residential units atop a luxury, full-service hotel, signals the return of this concept, which became popular just before the economic downturn. Several other Chicago mixed-use projects built over the past decade in Chicago’s Gold Coast area were based on a similar concept. The 67-story Hyatt Park Tower has 198 hotel guestrooms, 57 stories of condominiums, and 20,000 square feet (1,900 sq m) of retail space. The Waldorf Astoria Chicago (formerly Elysian Hotel & Residences) contains 160 ultra-luxe two-room hotel suites and 27 floors of condominiums. Both projects were designed by Chicago architect Lucien Lagrange. In the same category is the 96-story, five-star Trump International Hotel & Tower Chicago, which has 486 condominiums atop a 339-room hotel and 17 floors of office and retail space.

All three of these projects offer five-star service and amenities, and both the Waldorf Astoria and Trump International Tower introduced the popular Las Vegas condo-hotel concept to Chicago, offering individual condo owners the option of booking hotel guests into their condo-hotel room when they are not using it.

Another recent mixed-use project, the soaring 87-story Aqua Tower, which is part of the 28-acre (11 ha) Lakeshore East master-planned development by Chicago’s Magellan Development, has 745 residential units atop a 334-room Radisson Blu hotel, plus retail and office space. Designed by environmentally conscious Chicago architect Jeanne Gang of Studio/Gang Architects, this thought-provoking, contemporary project received a Silver rating from the LEED program in July.

Opening in November 2011, the four-star Radisson Blu is a $125 million joint venture of Magellan and Minneapolis-based Carlson Hotels, financed by Hartford, Connecticut–based Cornerstone Advisors, investment manager of MassMutual’s equity real estate investments. In 2012, a 75 percent interest in the hotel was sold to Qatari investment firm Al Faisal Holdings, says Robert Kleinschmidt, Carlson executive vice president and chief financial and development officer for the U.S. market.

Carlson chose Chicago to introduce the Radisson Blu brand to the U.S. market, Kleinschmidt notes. “The opportunity to develop a hotel in MacArthur genius Jeanne Gang’s Aqua Tower matched the brand’s commitment to world-class design and sustainable hospitality,” he says. “Chicago’s historic role as a standard-bearer for architecture and innovation made selection of the city all the more easy. Chicago as an incubator of innovation in design was a clear fit.”

Creating Value in Obsolete, Historic Structures

Chicago’s large stock of aging, iconic commercial buildings has inspired another hotel development trend: a large number of the city’s historic, architecturally significant landmark office buildings are being converted to conventional or boutique hotels.

Located in the financial district, across the street from the Federal Reserve Bank building, the JW Marriott Chicago opened in July in the Continental & Commercial National Bank Building, designed by acclaimed architect and planner Daniel Burnham.

Lagrange spearheaded the building’s $396 million restoration and conversion of the lower half of the 20-story structure to a 610-key hotel. The upper half of the project, owned by Chicago developer Prime Group and a Germany-based investment syndicate, remains office space.

Lagrange—who also converted a 1910 classical revival Beaux-Arts landmark building designed by Marshall & Fox to the Blackstone Hotel, and the 1920s art deco Carbide & Carbon Building to the Hard Rock Hotel Chicago—says old office buildings make ideal hotels because they typically have big floor plates, large rooms, tall ceilings, and architecturally unique details. He also notes that conversion projects can be completed faster—within 12 to 14 months—than new, ground-up construction, saving time and money.

“As a building, the Continental & Commercial National Bank Building, works perfectly for a hotel, and everything fell into place,” says Lagrange. The building had a large, 9,000-square-foot (836 sq m) hall suitable for a ballroom, and the hall’s ceiling had a height of 100 feet (30.5 m), he notes, which provided enough space to create another level for a junior ballroom and still have a 40-foot (12 m) ceiling.

The ground-level floor plate was spacious enough to accommodate a lobby, the kitchen, and retail services. Also, individual offices had two windows per room and a basic room size 16 feet (4.9 m) deep, which Lagrange says is ideal for a Marriott guestroom.

Advantages of Repositioning

“Taking a building that doesn’t work anymore as an office building and turning it into a hotel creates value,” Lagrange emphasizes. “You could spend millions renovating it for use as an office building, but you will still have an obsolete office building. The conversion saves the building, and gives it a new financial life,” perhaps extending its use for another 100 years, he says.

“And because this is a perfect use for this building [the Continental & Commercial National Bank Building], the conversion changes the life of the street,” adding a hotel, restaurant, and bar to a street that previously was void of amenities, Lagrange says.

John Rutledge, founder and president/chief executive officer of Chicago-based Oxford Capital Group, which has completed ten hotel conversion projects, points out that old office buildings usually have good locations in the city’s core. They also have good “bones” and are architecturally beautiful structures with striking detailing, he says. “These are art gems with classic visual appeal. You can’t justify replicating this in a modern building.”

From a financial perspective, old commercial buildings can be repositioned at a significant discount, Rutledge says—well below replacement cost or the cost of new construction. “Frequently they are local and national landmarks, so [they] get historic tax credits,” he notes.

The project also may qualify for city tax incentives if it is in a tax-incentive financing district or repositions an empty office building. His company recently developed the swanky 316-key Langham Hotel Chicago, located at 330 North Wabash Avenue in the north Loop/River North area, which opened in July on the first 13 floors of the IBM Building. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, this 52-story tower—which the Chicago Tribune called a “starkly rectilinear monolith” of anodized aluminum and bronze-tinted glass—transformed the city’s skyline when it opened in 1972.

Dirk Lohan—Mies’s grandson, cofounder of Chicago architectural firm Lohan Anderson, and designer of the Langham’s ground-floor lobby and ballroom—says that in the 1970s the building represented a “pioneering jump north of the river, as that area was underdeveloped at the time.” He also notes that the building’s midcentury modernist architecture gives it high visibility on the street. “There’s a generosity in this building you don’t get in newer buildings,” he adds. For instance, the 15-foot (4.6 m) depth of the former offices provided space for spacious guestrooms with very large baths.

Oxford Capital also recently teamed up with Angelo, Gordon & Co., a privately held investment advisory firm based in New York City, to purchase the London Accident and Guarantee Building, a 22-story landmark on Michigan Avenue with classical architecture that was built in the 1920s. Oxford Capital plans to convert this building to a hotel, too, as part of a transformation project to connect a stretch of Michigan Avenue near Millennium Park to the Magnificent Mile shopping district north of the Chicago River.

U.K.-based Virgin Hotels has also chosen a Chicago landmark, the Old Dearborn Bank Building, to house its first hotel in the United States. Designed by Chicago architects and brothers Cornelius W. and George Leslie Rapp and completed in 1928, this 27-story art deco building at 230 North Wabash Avenue was among the first office towers built north of the river. The hotel will have six food and beverage venues and a world-class spa.

Customers of Richard Branson’s Virgin Atlantic and Virgin America airlines will help fill this boutique hotel’s 250 guestrooms, suggests Doug Carrillo, vice president of sales and marketing for Virgin Hotels, North America. “We feel that this offering will play to our loyal Virgin customers,” he says.

Building Midmarket Capacity

New York City hotel mogul Ian Schrager’s new 235-room Public Chicago, which opened in 2011, is an example of both the financial benefits of repositioning historic buildings and of how boutique hotels are meeting growing demand for competitively priced accommodations with services that meet the needs of both business travelers and budget-conscious tourists.

Backed by Morgan Stanley, Schrager paid $25 million for the Ambassador East Hotel, a 1926 landmark, and invested $35 million redesigning and renovating it to boutique standards.

In a December 2011 interview with Travel & Leisure magazine, Schrager noted that his no-frills hotel, with rooms rates starting at $140 a night, offers an alternative to pricey accommodations. “There’s a paradigm shift in this country,” he says. “People want to be more modest. Even if they have the money, they don’t want to spend it extravagantly anymore.” His aim is to provide guests a memorable experience without the unnecessary luxury services that most people neither need nor use.

He compares his hotel to a Hilton Garden Inn or Marriott Courtyard combined with the service of a Four Seasons. But unlike chain hotels, the Public Chicago is a slick, hip, unique project programmed to appeal to gen-Y guests. It offers various places to linger and socialize, including a lobby that doubles as a community office with a huge Christian Liaigre table occupied by five MacBook Pro computers. There also is an in-house restaurant/bar, a coffee bar, and a fitness center.

Similarly, Kimpton’s four Chicago projects are boutique hotels that appeal to certain guest types. All are pet friendly and LEED certified. With the exception of the Hotel Palomar, which is a contemporary structure, the Kimpton hotels occupy landmark buildings and offer guests a unique, historic experience. The chain’s Hotel Burnham and Hotel Monaco also are part of Retrofit Chicago’s Commercial Buildings Initiative, the city’s sustainability program, which requires a reduction in energy use of at least 20 percent from 2010 levels.

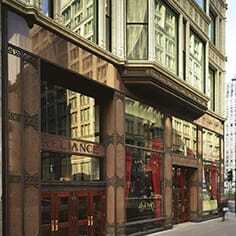

Constructed in 1895 by legendary Chicago architects Daniel Burnham and John Root, the 14-story, 122-room, select-service Hotel Burnham, located at the corner of State and Washington streets in the north Loop area, was one of the world’s first steel-frame skyscrapers and at the time was one of Chicago’s tallest buildings.

Kimpton’s 483-room, full-service Hotel Allegro, developed in 1894 as the Bismarck Hotel by German brothers Emil and Karl Eitel, is located at the heart of the theater and business districts and has hosted countless artists, entertainers, politicians, and celebrities over the past century.

And the select-service, 181-room Hotel Monaco restored the headquarters of the old D.B. Fisk Company, a hat maker, with an eye to preserving this steel-framed, brick-masonry building’s charming, terra-cotta decorative elements that make it both historic and unique.

Chicago’s Hotel Future

“The hotel space is an exciting place to be right now,” says LaBerge of Marcus & Millichap. “Arguably, hotels provide one of the fastest-growing, most attractive yields.” But he notes that there is an ongoing argument about whether big, full-service hotels will be built in the future. “They’re difficult to build and not as profitable versus select service,” he says. Also, boutique hotels fit the select-service model and now constitute a national trend, he notes.

“This makes sense,” LaBerge continues. “There’s greater demand for a Hilton Garden than a full-service Hilton.” However, the select-service model of the future may look more like the Public Chicago, he says.

Noting that revenue per available room is improving, Sahn of CBRE points out that groups are buying up old buildings to convert to hotels because the midmarket is underserved. “They feel that if they come in with the right management, they can penetrate this market in a positive way,” he says.

And despite the number of large luxury hotels coming on line or under construction, Sahn agrees that the future of this product type is uncertain. “Unlike coastal markets, Chicago is a Midwest city and will never be a $300- to $400-per-night market,” he says.” It will be interesting to see what the Chicago hotel market looks like five years in the future.”