Spencer Glendon, senior fellow at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts, presented the history—and the potentially dire future—of real estate development to attendees of the 2020 ULI Virtual Fall Meeting.

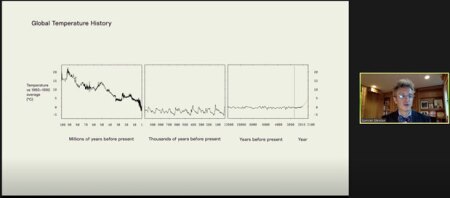

About 200,000 years ago, he said, humans’ ancestors were migratory, chasing good weather in a highly variable climate. But about 12,000 years ago, “something very important” happened: the climate stabilized and humans were able to settle down, inventing agriculture and developing communities. “The climate stabilized and humans invented real estate,” Glendon said.

But on the course of atmospheric warming that the world is following now, he warned, those migrations could begin again as people flee areas that are too hot for habitation. These would include much of the U.S. South, Arizona, and California, as well as multiple other parts of the world. The more rapidly the world warms by as much as 2 or the catastrophic level of 3 degrees centigrade, the more chaotic and possibly violent those migrations will become, he warned.

“Large-scale movements of people are almost never orderly,” he said.

The beauty of zero is that it’s a clear goal that can inform any decision, and it helps differentiate sustainable practices from less sustainable.” Spencer Glendon, @WoodwellClimate at #ULIFallFind out more: https://t.co/o17dokXcby #netzero #zeroemissions #sustainability pic.twitter.com/CI9wfYOKgz— Urban Land Institute (@UrbanLandInst) October 15, 2020

The good news, according to Glendon: “Three degrees [centigrade] doesn’t have to happen; 1.5 is technically possible.” We control the variables that matter—carbon dioxide and methane.

“What you must do now is focus on one number. It’s a number that’s not in your spreadsheets now, but it has to be. . . . It’s zero. . . . We need to cut emissions by 50 percent in this decade, and then 100 percent by 2050. That’s a clear goal. If your spreadsheet doesn’t do that, it’s a problem.”

“Electrifying everything is probably the first thing to do for your industry,” he noted.

Glendon, who holds a doctorate in economic history from Harvard and spent 18 years as a macroanalyst, partner, and director of investment research at Boston-based Wellington Management, called on the real estate industry to lead the effort to push for net-zero carbon emissions.

“Your decisions last,” he told real estate developers, and urged them to lead the drive to achieve net-zero carbon emissions. “Exert pressure on others,” he said. “You can’t do this alone. You must demand better regulation . . . beg for regulation.”

He added, “You’re all here because of regulation.” In previous centuries, fires routinely ravaged cities, culminating in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. After that disaster (which destroyed 17,500 buildings and killed about 300 people), insurance companies got together and refused to issue policies in cities unless they adopted building codes and established reliable fire departments. “The real estate industry pressured cities to regulate,” Glendon said.

Similarly, long-term loans will not be made in a rapidly warming climate that could render communities undesirable or uninhabitable. “Duration will disappear from financial markets very soon,” he said.

Current resilience measures are insufficient to achieve the change needed, Glendon said. For example, the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system is too narrowly focused to achieve systemic change, which could involve municipal sewer, electricity, and transportation systems.

The longer society waits to change regulations—say, prohibiting combustion engines in vehicles—the more harsh those rules will have to be once they are imposed, he said.

“We have to get to zero” Glendon said. “Yes, it’s hard, but it’s simple.” It requires imagination, courage, and paying attention.

ULI Virtual Fall Meeting registrants can access an on-demand version of this session. Register for the Virtual Fall Meeting and access all the sessions on demand.