MANILA—As asset returns across Asia continue to shrink, investors throughout the region are turning increasingly to developing markets to look for better deals.

In principle, the Philippines would seem to be an ideal destination. With a strong economy serving as a catalyst, year-on-year investment yields and capital values grew 8.8 per cent and 7.4 per cent, respectively, in Manila during the last quarter of 2017, according to JLL.

It is perhaps surprising, then, that foreign real estate investment in the Philippines has failed to generate much traction. At a ULI Capital Markets Forum event held in Manila in January, 20 prominent developers, asset managers, and brokers gathered to discuss this issue and others relating to local markets.

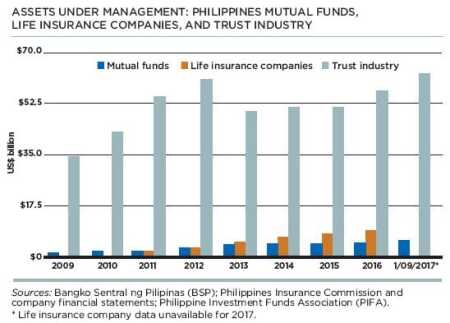

In ULI and PwC’s Emerging Trends in Real Estate® Asia Pacific 2018 report, published in December, Manila’s investment prospect ranking slipped to 18th among 22 regional cities, down from a high of third the previous year. The reason for the decline, fundamentally, is that foreign funds are looking elsewhere because a glut of liquidity in local financial markets means risk/return parameters do not stack up: local developers have no need for expensive foreign capital when in-country financing is cheap and easy to obtain.

There are a number of other reasons why the level of inbound capital remains significantly lower in the Philippines than elsewhere in Southeast Asia:

- Regulatory restrictions limit foreign equity interests in local property assets to 40 percent. Several forum participants identified this as the single biggest deterrent to foreign investment in Philippines real estate.

- Domestic markets are controlled by a handful of big players who generally have no need for expensive foreign capital.

- Good partners are otherwise hard to find and, regardless, are often slow to react to emerging opportunities.

- Banks are super liquid, and the cost of debt is therefore super low. Foreign private equity funds, which expect returns in the high teens or low 20s, find it hard to compete when local banks are offering loans for the same deal at 2.75 per cent.

- A number of rich families hold land banks that, in principle, would be ideal for development, but those families generally lack experience in navigating real estate projects.

“As a foreign investor, you could either buy property stock or invest directly, but it’s going to be tough,” said Raymond Rufino, copresident of the Net Group, a Manila-based office developer. “You have to go into another market, get comfortable with a local player, forge that partnership. It’s not going to happen overnight, and there really aren’t too many options.”

No Tax Break for REITs

One way for foreigners to invest in Philippines real estate would be through domestic real estate investment trusts (REITs). For now, however, this option remains on hold. A REIT regulatory framework was introduced years ago, but authorities have so far refused to provide tax exemptions needed to provide reasonable profits for REIT shareholders.

A resolution seems no closer today despite hopes that the Duterte government would move to break the impasse.

The problem is one of image rather than fundamentals. “On the one hand, the government is trying to increase its income because they have so many new obligations to fund, whether it’s infrastructure or social services,” said one developer who did not want to be quoted by name given the sensitivity of the subject. “On the other, the perception is that REITs are just tax breaks for rich developers, most of which are family owned. So, the Department of Finance is struggling to find a structure the public will [accept].”

However, REITs would provide not only an avenue for unallocated capital to be put to work, but also promote greater efficiency in the way capital is allocated.

“It allows more economic activity, more investment, and more entrepreneurship,” said Eric Manuel, vice president and head of real estate at Manila-based investment bankers Primeiro Partners. “There are a lot of stranded assets here in the Philippines that are family owned or trust owned and have no way to be monetised because capital is not flowing fast enough. The people who have capital are thinking about other things, bigger things. The REITs would help sbecause they allow you to amalgamate a number of assets and start monetising them through the public markets, which, by the way, are dying for yield.”

Deal Flow Picking Up

Notwithstanding these constraints, however, several participants suggested that local developers are becoming increasingly willing to work with foreign investor partners and that the flow of internationally sponsored deals is gradually picking up.

“There is money coming into the Philippines, and there are legal, profitable ways to set up shop for foreign investors,” said Christophe Vicic, Philippines country head for real estate advisory firm JLL. “It’s not easy, and it’s not necessarily with tier-one developers. But even in very difficult real estate investments environments there are opportunities for people ready to work with local partners.”

Historically, foreign investors have been more likely to play a role in deals involving the business process outsourcing (BPO) sector, usually involving call centres where tenants are international companies. But growth in this sector has recently levelled off as automation and artificial intelligence (AI) technology begin to eat into what is a maturing industry. Going forward, therefore, both local and global BPO markets will probably begin to decline.

“The consensus is that over time certain tasks and job functions will disappear,” said one developer active in the industry. “So the regular job of the call centre agent who just picks up the phone and does simple customer support—that job will probably not exist in ten to 20 years.”

While the BPO sector will necessarily adapt (by way of increased specialisation, for example) and the AI industry will itself generate a certain amount of employment, the future remains opaque. The only certainty is that these new technologies will be less labour intensive than their predecessors.

Niche Asset Classes

The key to finding deals that work for both international and local partners is to focus either on niche asset classes or on areas that require an element of expertise to justify their higher cost of foreign capital. And with local investors beginning to focus more on asset management or on more adventurous types of investing to boost profits, the need for operational expertise is coming increasingly to the fore.

The following types of new asset classes are emerging.

- Worker dormitories. This type of housing is increasingly in demand in Manila as traffic problems worsen and daily commutes lengthen. While operating dormitories means dealing with far larger numbers of occupants than landlords are accustomed to, yields are supposedly comparable to those for local office projects.

- Industrial parks and logistics. Foreign capital may also have an edge in these areas. “As we began diversifying out of Metro Manila and into the industrial/logistics space, we started looking at investors on a more strategic basis,” said Eric Manuel, vice president and head of real estate at Primeiro Partners.

“So, for example, where foreign funds had relationships with global manufacturing firms or retail coming from China to the Philippines, they could provide not only the capital, but also the tenants. That allowed us to de-risk not just the development or the capital side, but also the tenant portion.” - New industry cities. Another area that may prove fruitful for foreign capital involves construction of “new industry cities”—large-scale greenfield developments built in partnership with the government on a public/private partnership basis.

At least one large mainland developer is looking at transplanting to the Philippines the well-established Chinese model involving mixed-use, integrated developments anchored by a large industrial park or business park. Some local investors are ambivalent about this model, however, partly because Chinese developers may be unwilling to accept a 40 per cent limit on equity ownership, and partly because the lack of suitable land means such facilities will probably be consigned to unfavourable locations far from city centres. - Investments in provincial areas. This is another option. Local developer Double Dragon, for example, has built a portfolio of some 64 community malls in second- and third-tier cities, with another 25 in the pipeline. Designs are standardised, with each facility about one-tenth the size of a typical large mall.“It’s like a fast-food branch,” said one developer familiar with Double Dragon’s strategy. “They build it in about eight months, and one-third is grocery. Each one looks exactly the same, but your menu items are the typical brands—all basic necessities. It’s not the type of stuff you would buy online, for example, so it’s very e-commerce defensive.”Many of the stores and products on offer are owned by large conglomerates that are also partners in the project. The community mall concept is partly demand driven, but it is also a function of supply-side conditions because big cities are saturated with product, leaving second- and third-tier locations the only options for retailer expansion. This template seems to be a plausible model in other developing markets, too.

Debt Financing Emerges

Debt financing is another area drawing attention from foreigners. Bank lending has long been the go-to source of deal financing in the Philippines, but several international funds are exploring opportunities in this area, in particular by providing mezzanine funds to supplement developers’ own in-house financing strategies.

In addition, securitisation is beginning to emerge as an alternative financing model, with investors looking at bundling and reselling mortgages held by larger developers and real estate portfolios of local banks, which, by law, may not allocate more than 20 per cent of their total lending to property portfolios.

But, securitisation remains a thorny issue given the lack of a regulatory framework, bank reluctance to divest better-quality loans, and the historical legacy left by the meltdown of the American securitisation market during the global financial crisis. Progress in developing this model the Philippines is therefore likely to be slow.