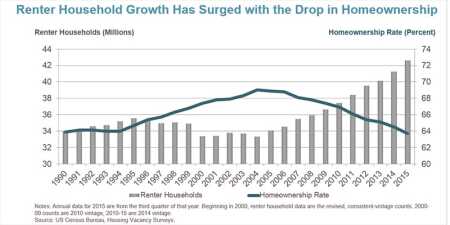

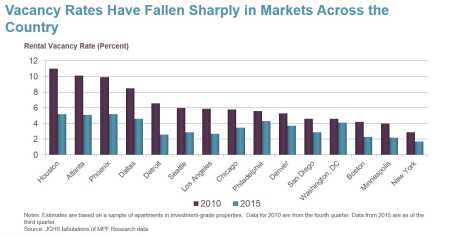

According to America’s Rental Housing: Expanding Options for Diverse and Growing Demand, released by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS), the United States has seen an unprecedented increase in those living in rental housing, with nearly 9 million rental households added since 2005. With 42.6 million families and individuals now renting, vacancy rates for rental housing have plummeted to 30-year lows (7.1 percent nationally), and inflation-adjusted rents have increased annually by an average of 3.5 percent.

The report was released in December at the Newseum—an interactive museum of news and journalism in Washington, D.C.—and was accompanied by a panel discussion, with the proceedings broadcast live. “Rents are rising, and against the backdrop of the fact that we have not seen a real rebound in wages or income, it’s putting the squeeze on a lot of people,” summarized Chris Herbert, director of the JCHS. “So the whole thing builds to the punchline of where we are, and there are record levels of people struggling to find rents that they can afford.”

With household incomes largely stagnant at 1995 levels, the number of cost-burdened renters (i.e., those paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing) has increased from 14.8 million in 2001 to 21.3 million in 2014. Although multifamily housing permitting and construction have steadily increased since 2010, supply still lags behind demand in most markets—particularly for low- to moderate-income renters.

The number of “severely” cost-burdened—those paying more than 50 percent of their incomes for housing—also increased from 7.5 million to 11.4 million during the same span. Overall, nearly 50 percent of renters are cost-burdened, with 26 percent categorized as severely so. In 2001, those figures stood at 41 and 20 percent, respectively.

The cost burden especially affects lower-income households. In 2014, 84 percent of renters earning under $15,000 a year were cost-burdened, with 72 percent of those saddled with severe burdens. For households earning $15,000 to $29,999 per annum, the cost burden was 77 percent. Households paying such a high percentage of income for rent must then sacrifice other necessities. Of those low-income households paying more than half of their incomes on rent, 38 percent less is spent on food, 55 percent less on health care, and 45 percent less on retirement savings than those living in affordable housing.

But cost burdening is not limited to low-income households, and in recent years has steadily made its way up the income spectrum. For those making $30,000 to $44,999, 48 percent are cost-burdened; and for those making $50,000 to $74,999, the percentage is 21 percent—nearly double the 12 percent recorded for the demographic in 2001. The figure shrinks to 5 percent for those making over $75,000 annually. The percentage of cost-burdened renters is also well over 50 percent among two prominent demographics: those over 65 years of age (55 percent) and those under 25 (62 percent). Demographics also play a key role in the cost-burden equation. While over 80 percent of those with yearly incomes below $15,000 in both Washington, D.C., (83 percent) and Detroit (85 percent) are cost-burdened, more than 80 percent of D.C. renters earning $30,000 to $44,999 are as well, compared with 45 percent in Detroit.

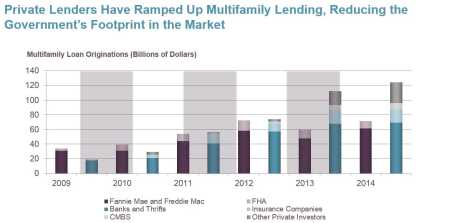

“In the lower-income households, it doesn’t really matter where you live,” Herbert said. “Private developers just can’t build housing that’s in that range. So I think we really do need to think about how it is that we can expand our support for rental assistance to low-income households, and that’s probably a federal [issue]. But as you move more into the moderate-income housing categories, there are ways in which the private sector can potentially meet that demand for housing, but there are a lot of constraints.”

One of the issues for developers, Herbert said, is that with such strong demand for high-cost rentals and a limited amount of land available for housing in metropolitan areas, developers are more likely to accommodate the higher-income renters to maximize returns. “So we need to make sure that there’s more land available that is zoned for higher-density housing, and you’ve got to make sure that the approval process isn’t any more complicated than it needs to be, because time is money,” he said. “More available land and a simpler approval process will allow developers to build to a more moderate-income price point.”

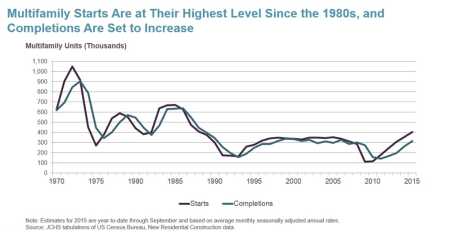

In terms of new product being constructed, there is both good news and bad news. In 2015, multifamily construction starts (with 96 percent of those units designated as rentals) were projected to top 400,000, and there were 313,000 rental units completed—the strongest figures since the mid-to-late 1980s. Those encouraging numbers followed a 2013 that saw 264,000 completed units—an increase of 35 percent over the previous year. However, most of the new construction is aimed at higher-income groups. According to the report, the median asking rent for new market-rate apartments has been rising in recent years, reaching $1,372 in 2014, up by more than a quarter from 2012. And the asking rents for 60 percent of the newly constructed apartments exceeded $1,250 per month, with only 10 percent available for under $850 per month.

Complicating the picture is the loss of older, deteriorating housing stock—units that typically command lower rents—further depleting the supply available for low- and moderate-income renters. According to the report, the net number of low-cost rental units increased just 10 percent in 2003–2013 while the number of low-income renter households competing for that housing rose by 40 percent. And the net gain in moderately priced units (with rents of $400 to $799) was 12 percent, while the increase in renter households who could afford only these units was 31 percent.

“In 2015, rental housing in America is a tale of two markets, where upper-income renters are finding a healthier supply of housing choices and landlords and private sector investors are benefiting from higher rents, but too many families earning less than $50,000 per year are having to make trade-offs between putting a roof over the their heads and food on the table,” said Herbert in a statement released in conjunction with the report. “These negative trends are poised to go from bad to worse, as the most cost-burdened populations—minorities and the elderly—grow, and [as] incomes continue to grow more slowly than rental costs.”