Dallas residents called it Stonehenge. This Texas version of the English landmark, like a monument to unfulfilled dreams and lingering failures, was an arrangement of heavy concrete pillars constructed in the 1980s to support an ambitious pair of 50-story office towers in downtown Dallas.

But the Texas real estate market went south in a hurry in the 1980s economic crash, and the developer, Metropolitan Ventures, pulled the plug on the twin towers, leaving behind the support columns dubbed Stonehenge. The 50-story buildings were never built.

Companies left downtown Dallas in droves in the 1980s, and it went on to have the emptiest office market in the nation in the early 1990s. Stonehenge stood as a negative symbol for years.

But that era is over. Today, downtown Dallas is a different place. Stonehenge has been replaced by Hall Group’s new 18-story Hall Arts office tower—the first office project built in the central business district in years. In downtown’s Arts District, new performance halls and museums have been erected. The new Klyde Warren Park, a transformative downtown recreational haven built over a below-grade freeway, attracts scads of people every day of the week. And perhaps most important, dozens of older office buildings have been converted to residential use, giving rise to a more active street life.

After decades of efforts—and some missteps—the core of Dallas has been transformed. No single strategy or project is credited for the turnaround. But the emergence of residential development is widely acknowledged as having been a spark plug.

Downtown Living

“The major driver for the change was the residential component,” says John F. Crawford, chief executive officer of Downtown Dallas Inc., a nonprofit advocate for economic development. “In the urban core we’ve got about 10,000 people who live there, and in the greater downtown area there’s almost 50,000.”

In recent years, developers created thousands of residential units, primarily apartments for rent, from old office properties that were largely obsolete for corporate use but which held tremendous value as dwellings for young professionals who thrive in urban environments.

One breakthrough was the redevelopment that transformed the landmark 31-story Mercantile National Bank building on Main Street, which was redeveloped as apartments in 2008.

The Mercantile building had been an eyesore for years. “The windows were falling out of it. It looked like Beirut after the war,” says Jack Gosnell, senior vice president with CBRE | UCR Urban in Dallas. Gosnell convinced representatives of Forest City Enterprises to tour the art moderne Mercantile building, and everything started to click.

Forest City Texas, with the assistance of tax increment financing obtained through the city, created a 213-unit residential rental community out of the Mercantile tower. It and three other buildings that were subsequently developed by Forest City now make up Mercantile Place, which has a total of 704 apartment units.

Downtown Dallas had seen smaller buildings redeveloped, but the Mercantile project made Dallas residents marvel at the transformation. The project demonstrated the possibilities for the future.

“Forest City took this black hole on Main Street and turned it into a really cool apartment building,” says Ian Pierce, vice president of communications at Weitzman Group, a Dallas-based real estate firm.

Another key redevelopment at a separate site transformed the 1926-vintage Davis Building at 1309 Main Street into 180 loft apartments. The developer, Hamilton Properties, a prolific real estate firm led by Ted Hamilton and his father, Larry, has tackled a number of redevelopment projects in and around downtown Dallas. Hamilton Properties is currently transforming an old Ramada Inn on the south side of downtown into a 237-room boutique hotel that will be called the Lorenzo.

One of the largest redevelopment projects underway is the $220 million transformation of downtown’s historic Statler Hilton by Dallas-based Centurion American Development Group. The 19-story hotel will become the Statler Hotel and Residences, with 219 apartments and 159 hotel rooms operated under Hilton’s Curio brand for historic hostelries. The Statler, which opened in 1956, in its heyday presented performances by Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra on its ballroom stage before closing more than a decade ago.

But after scores of redevelopment projects, the game is changing in downtown Dallas, Crawford says.

“We no longer have any older buildings left in downtown anymore. They’ve all been converted to residential or some form of adaptive reuse,” Crawford says. “So we are now moving to new construction.”

Within walking or biking distance of the central business district, residential construction has been ongoing in full force in the districts and neighborhoods on the edge of downtown, such as Uptown, the Cedars, Deep Ellum, and Victory Park.

“That’s the big story in what’s going on in Dallas—the multifamily demand by the young urban professionals,” says Ken Reese, executive vice president of Hillwood Urban, part of the Dallas-based Hillwood real estate organization founded by Ross Perot Jr.

The 75-acre (30 ha) Victory Park, a mixed-use development started by Hillwood on a reclaimed brownfield site over a decade ago, is adding 1,800 units of new residential units to the downtown mix. Victory Park now has four new high-rise towers and a mid-rise apartment project under construction by a strong lineup of multifamily developers that includes Camden Property Trust, Novare Group, Greystar, Lennar Multifamily, and Genesis Real Estate.

Downtown’s residential boom eradicated that lonely, unpopulated feeling that had plagued the central business district for decades. “Our downtown used to evacuate at night. By 6 p.m. all the people were gone,” says Phil Puckett, executive vice president in the Dallas office of CBRE.

Downtown Dallas, like many downtowns across the country, lost momentum in the 1960s as new freeways and affordable homes for the middle class in the suburbs sucked growth out of the cities. Many businesses followed as office buildings rose on the suburban prairies.

Before the 1960s were over, the Dallas City Council tried to stop the outward tide by adopting the recommendations of urban planner Vincent Ponte, who designed a system of downtown tunnels and underground retail shops linking the major buildings. The city leaders were prodded along by Esquire magazine, which ran a headline on its cover in June 1968 reading, “Vincent Ponte Should Have His Way with Dallas.”

But Ponte’s way was the wrong way, city leaders later discovered.

Over the years, the tunnel system grew to more than two miles (3 km). It provided a convenient lunchtime amenity for downtown office workers but was blamed for choking off life and commerce on the street above.

“If I could take a cement mixer and pour cement in and clog up the tunnels, I would do it today,” said then mayor Laura Miller in a 2005 interview with the New York Times. “It was the worst urban planning decision that Dallas has ever made.”

In recent years, the downtown tunnel system has become disjointed and been deemphasized as some landlords closed off tunnel connections, breathing an extra measure of life into downtown streets and sidewalks.

“They have done a great job of turning it around,” says Dallas office broker Fletcher Cordell, a principal with the Transwestern real estate company.

A Spark from Parks

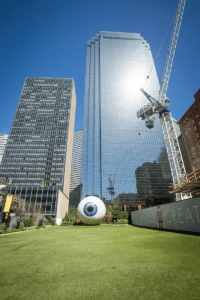

The 30-foot (9.1 m) Eye sculpture by Chicago artist Tony Tasset was installed along Main Street in Dallas. In the background at left stands the 32-story 1600 Pacific building, which was recently redeveloped by HRI Properties as hotel and apartment space; to the right is the 50-story Thanksgiving Tower. (© Hall Group)

When it comes to the downtown turnaround, nothing has been praised like the catalytic Klyde Warren Park, which opened in October 2012.

Built over the Woodall Rodgers Freeway, the 5.2-acre (2 ha) park effectively erased the barrier between downtown and the bustling Uptown district’s multifamily, retail, and office markets. Not only has Klyde Warren Park made it easier to walk to downtown, but it also draws large crowds to its heavily programmed activities of yoga and music performances, as well as a dog park and a playground. The success of the park, designed by the Office of James Burnett, a Solana Beach, California–based landscape architecture firm, has prompted city leaders to discuss a proposed expansion that could cover more of the freeway.

Klyde Warren Park generated a real estate boom. Rents for office buildings near the park have gone up as much as 60 percent since 2014, and prices for development sites, such as surface parking lots, have recently approached $400 per square foot ($4,300 per sq m) in some cases, says Puckett of CBRE.

Along Pearl Street, which borders the northern edge of the park, two office projects are under construction. A partnership of Trammell Crow Company and MetLife is building the PwC Tower at Park District, a 20-story, 500,000-square-foot (46,500 sq m) office tower slated for completion in 2018 with PwC occupying 200,000 square feet (19,000 sq m) of space. The building is part of the partnership’s mixed-use development, called the Park District, which also will have a 30-story residential tower and retail space overlooking Klyde Warren Park.

Across the street from the PwC Tower, Dallas-based Lincoln Property is developing a 260,000-square-foot (24,000 sq m), 25-story office project at 1900 Pearl Street.

The Lincoln Property site is adjacent to the Meyerson Symphony Center in the Dallas Arts District. The symphony building, designed by I.M. Pei, opened in 1989 and has been a cornerstone of an impressive collection of performance halls and museums built in recent years.

Downtown’s 68-acre (28 ha) Arts District, with more than a dozen visual and performing arts institutions, has been a growth generator in its own right. Nearby, the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, designed by Pritzker Award–winning architect Thom Mayne, opened in 2012 and has been attracting 1 million visitors annually.

The buildup of the Arts District created a welcoming environment for new residential projects, such as the 42-story Museum Tower condominiums, which opened in 2013.

Dallas developer Craig Hall, chairman and founder of Hall Group, produced the Hall Arts Center, the first new downtown office tower built in years. The first phase was an 18-story, 500,000-square-foot (46,500 sq m) office project built on the so-called Stonehenge site on Flora Street. The office building, which opened last year, was renamed KPMG Plaza at Hall Arts after its lead tenant.

Hall expects to break ground next year on Hall Arts Center Phase II, a high-rise residential tower with 44 condominium units for sale and an adjoining mid-rise hotel. Hall owns another parcel of land for a yet-to-be conceived Phase III project in future years.

But Hall says his eye is truly focused on placemaking, not just erecting new buildings in the Arts District.

“We need to energize the street life. We need to get people to stay and walk around rather than just come in their car to a symphony event and then get back in their car and drive somewhere else,” Hall says. “That’s my personal goal.”

To that end, Hall created a half-acre (0.2 ha) sculpture garden featuring the works of Texas artists, which is located at the side of the new office building and easily accessible to the public. The Hall building also has a 30-foot-tall (9 m) glass-walled lobby that fosters engagement with pedestrians on the sidewalk, says Eddie Abeyta, principal and Dallas design director for HKS architects, which designed the Hall building.

Abeyta, a key advocate for urban walkability in downtown Dallas, is one of seven professionals on the city’s Urban Design Peer Review Panel, an advisory group that reviews proposals for new developments. “We try to put people first and automobiles second. Dallas itself is very auto-centric, like most big U.S. cities,” Abeyta says. “But we are trying to learn and we are trying to improve. We want to make sure developers, architecture firms, and landscape firms are responsible about how these buildings touch and engage with the public realm.”

The Art of the Skyline

Downtown Dallas goes above and beyond changing the city on the sidewalk level. The city’s skyline evolved significantly in recent years for those viewing it from afar.

New signature bridges, designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, are becoming highly visible landmarks for the skyline. The 400-foot-tall (122 m), cable-stayed Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge, spanning the Trinity River, opened in 2012. It will be followed by another skyline-altering structure by Calatrava, the Margaret McDermott Bridge, slated for completion in 2017. Some believe the new bridges will become Dallas icons equivalent to the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

The Dallas skyline has been taken a step further toward distinctiveness with several landlords’ approach to lighting that has been gaining wide notice. The use of LED lighting on the exterior of a number of the city’s towers has gone beyond regular decoration to becoming a nighttime public canvas for commemorating celebrations, holidays, and social statements. For example, last year when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of gay marriage, the downtown buildings were lit in a rainbow pattern. Pink lighting supports breast cancer awareness, and patriotic red, white, and blue lighting comes on for the Fourth of July.

“I think Dallas was named one of the prettiest skylines of the world because of the lighted buildings,” says Linda McMahon, president and chief executive officer of the Real Estate Council, a Dallas-based nonprofit organization. “It’s beautiful. Every building is almost a work of art.”

In July, the downtown lighting conveyed a poignant message when the skyline turned dark blue as a sign of support for police after a sniper killed five Dallas police officers and injured seven others, plus two civilians. The racially charged killings wounded the soul of Dallas, but dialogue and healing are underway.

“It’s been a very emotional time,” McMahon says. “The police and the community are reaching out to each other. I think you’ll see positive things come out of it in terms of the strength of our community. We are a resilient place.”

Ralph Bivins is editor of Realty News Report, a Texas-based website and newsletter.