An ambitious experiment in sustainability-obsessed Fort Collins, Colorado, supporting development of the nation’s first major urban zero-energy district (ZED) is already hinting at important lessons for participating workplaces.

Along the Colorado Front Range, a grand experiment conducted during the summer of 2011 illustrates how the strategic integration of energy generation, storage, and conservation activities among participating employers can reduce an electricity grid’s overall energy load at critical peak-demand periods. As workplaces become increasingly energy-efficient, they also are destined to generate and store more energy on site. With new-wave “distributed generation,” electricity will ultimately be delivered in a far cleaner fashion than is generally the case with the mostly coal-powered mega–power plants that now feed American power grids.

Working with the city-owned electricity supplier Fort Collins Utilities (FCU) and several locally based clean-energy specialists, the five participating employers were able to collectively reduce peak-load demand on a designated microgrid within the ZED’s boundaries by more than 20 percent during test periods that lasted more than four weeks.

Judy Dorsey, an energy and mechanical engineer with Fort Collins–based sustainability consulting firm Brendle Group, notes that minimizing peak-period pressure on grid loads is the key to environmental friendliness—and to ZED self-sufficiency. With lower net demand from a grid’s customers during the highest-demand periods, there is less need for air-polluting coal-fired megaplants, she explains. Brendle Group helped three of the demonstration participants reduce their peak-period consumption.

As with net-zero buildings, the long-term goal of a ZED is for power users within the district to produce as much energy in any given year as they collectively need to draw from the grid. Employers involved in the Fort Collins Zero Energy District (FortZED) pilot were indeed able to demonstrate how workplaces can adjust to limit grid loads during the highest-demand periods.

The successful demonstration required considerable and wide-ranging investments in power generation, storage, efficiency, and control; and communication equipment, technologies, and strategies. In addition to strategically sited solar photovoltaic arrays, participants tapped into several new electricity generators powered by natural gas, biogas, and fuel cells, as well as various thermal- and energy-storage devices. Fort Collins city offices—which feature electric vehicle–charging stations—that participated in the program even looked to in-car batteries as backup energy sources during peak-demand periods, Dorsey notes.

Meanwhile, the participants and the utility also installed smart energy meters and other control mechanisms, giving facilities and energy professionals access to varying and sophisticated data that monitored electricity usage and pricing at the property and employer levels. Indeed, a key element of the zero-energy concept entails having the utility signal the customer to cut back usage—such as intermittently shutting down air conditioning or heating of certain spaces—when the ZED’s overall demand approaches peak levels.

Using these mechanisms and all the data they generated, the participants were able to demonstrate how workplaces within tomorrow’s ZEDs will exhibit “more conscious moment-by-moment energy use as operators are supplied with real-time data,” says Jenn Vervier, sustainability director at New Belgium Brewing Co., the biggest private employer participating in the program.

Not only did New Belgium install smart meters and controls to better track energy use and coordinate peak-period reductions with FCU, but the brewer also can now generate well over half of its peak energy needs on site, thanks to generators and solar panels acquired in conjunction with the FortZED demonstration.

The successful demonstration relied on resources of numerous parties, Vervier says. The largest participant was downtown’s employment anchor, Colorado State University (CSU)—home of the highly regarded CSU Engines Lab, which provided technological expertise.

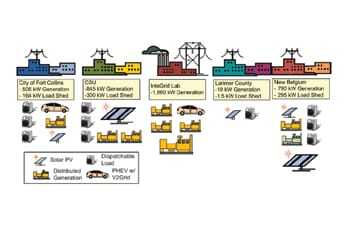

The endeavor, funded in part through the U.S. Department of Energy’s Renewable and Distributed Systems Integration (RDSI) initiative, offers several local tech outfits opportunities to generate revenue while demonstrating their capabilities, says Steve Catanach, FCU’s light and power manager. For example, some of the critical software that helped control and integrate participants’ on-site generation and storage (“distributed generation”) and conservation-minded load-shedding (“demand-response”) activities was developed by the local firm Spirae. The Department of Energy provided $6.3 million in federal economic stimulus–related grants to help fund the FortZED RDSI’s efficiency-improvement and power-generation investments and testing processes. Participants, local consultants, and FCU chipped in another $5.1 million. The other participants are Larimer County sites and the InteGrid Laboratory—a power system testing-and-development center affiliated with the Engines Lab and owned by CSU and Spirae.

New Belgium’s and other participants’ use of diesel-fueled electricity generators during the demonstration, however, does not portend that this relatively dirty fossil fuel will play a significant role in future ZEDs’ distributed-generation sources.

RDSI participation in FortZED was a limited technology-testing pathway helping model multiple-resource integration prospects, Catanach says. Full-fledged future ZEDs are expected to rely more on clean and renewable resources including generators running on clean fuels, as well as solar photovoltaic arrays, wind turbines, and ground-source heating and cooling systems.

How It Worked

The five participants in this limited-scope demonstration were able to exceed the minimum goal of reducing the peak-period load by 20 percent within a commercial-heavy microgrid served by two feeders (i.e., main distribution power lines) tied to FCU’s Linden power substation. The combined peak-load-reducing capacity of the various RDSI-related improvements and strategies averaged just under 3,500 kilowatts (kW)—which is significant for a microgrid with a peak-load average of approximately 15,000 kW.

Through their combined demand-management conservation efforts, the participants reduced peak demand on the grid by roughly 775 kW. Their half-dozen new solar photovoltaic arrays, multiple on-site generators, and other distributed-generation equipment can collectively provide nearly 2,700 kW. On-site generators accounted for 56 percent of the overall load reduction attributed to RDSI-related resources, while juice generated by solar photovoltaic arrays represented about 12 percent.

The RDSI initiative aims to reduce reliance on the giant (and often coal-fueled) power plants that feed the nation’s grids by integrating renewable and other utility customer–generated power, load-shedding strategies, energy storage, and thermally activated and related technologies into electricity distribution and transmission systems.

The test-area feeders served just a portion of the designated FortZED territory—which amounts to about 10 percent of the city and includes some 7,000 FCU electric accounts. FortZED covers much of the city’s downtown area, the CSU campus to the south, and the Poudre River corridor to the northeast—home to New Belgium.

RDSI-tied improvements to New Belgium’s workspaces illustrate what might be in store for other large employers as more ZEDs are established around the country. Now one of the nation’s biggest craft breweries, New Belgium installed what chief electrician David Benavidez refers to as “utility-grade” smart meters better able to track the use and cost of grid-based energy in real time—as well as the company’s substantial on-site generation.

The more sophisticated data give New Belgium a clearer handle on its energy consumption, sourcing, production patterns, and corresponding costs. “It helps us see just where we’re wasting energy, where we could generate more efficiently,” says Benavidez.

The technology also allowed New Belgium’s facilities team to respond to signals from FCU during the RDSI demonstration periods and temporarily shut down certain high-consumption equipment—most often air-conditioning systems—when asked. And as is the case with InteGrid and some of the participating city facilities, New Belgium can run its own generators fueled by diesel or cleaner natural gas—and, with certain machinery, even biogas (gas processed from materials such as agricultural waste).

New Belgium’s two new generators can combine for nearly 800 kW of capacity, with the newer (and larger) of them able to run on the methane the company produces and stores on site as a byproduct when it cleans wastewater. And its new solar array has a capacity of 200 kW.

Accordingly, when the sun is shining and the generators are running, New Belgium can produce about 1,000 kW of energy on site—well over half its current typical peak of 1,700 to 1,800.

New Belgium’s jump-start investments totaled roughly $3 million, with the company covering half the costs, stimulus funds covering another quarter, and the balance covered by donations, discounts, and in-kind contributions from participating vendors. The city and FCU likewise provided plenty of support, Benavidez stresses.

An ongoing challenge that facilities managers will face as ZEDs emerge is to devise strategies that can substantially reduce peak loads without negatively affecting workplaces and their core activities, including thermal comfort and noise levels in the workplace.

Beyond interrupting heating and air conditioning during times of peak load, other interventions might include shutting off swaths of artificial lighting—or, as in the FortZED demonstration, relinquishing the comfort and tranquility of electric-powered water fountains at least temporarily on hot summer days.

Temporarily shutting down the air conditioning in select New Belgium workspaces had far less effect on thermal comfort than management anticipated, Benavidez notes. “We learned we can [comfortably] live without some of the things we thought we needed,” Benavidez says.

With the energy-generating assets on site—and with more detailed data available—New Belgium is now far better positioned to make cost-effective decisions about operations and energy-related investments as FortZED development progresses. “We’re now trying to determine the best strategies and schemes for our future as we continue to grow,” Benavidez says.

Particularly at an environmentally conscious company like New Belgium located in a sustainability-minded community like Fort Collins, “people want to know that they are an integral part of a larger system working to reduce our collective environmental impacts,” adds Vervier.

Going forward, Dorsey expects ZED resources and strategies to become more visible at participating workplaces. Beyond all the new-wave building design and operational strategies aimed at limiting energy consumption, workplaces within ZEDs will presumably highlight information demonstrating to employees and visitors how energy strategies and individual decisions affect the bottom line.

For instance, Dorsey expects the development of ZEDs to make “energy kiosks” standard features in participating buildings. Such kiosks feature highlighting and performance-reporting tools and provide near-instant feedback on usage levels, which will reinforce how business operations affect energy consumption.

As for FortZED, Catanach sees no reason why additional peak-load-reducing demonstrations can’t be replicated on a larger scale as the district continues to evolve. Meanwhile, the city and its utility continue improving meter data-management and demand-response capabilities at homes and businesses citywide, while also tapping into the RDSI experience as they incorporate utility planning into the city’s land use plan update. “All of this will help toward getting FortZED further established,” Dorsey says.