No introduction required for the Empire State Building, likely the most famous office building in the world. Already an icon and a historic landmark, it is also becoming a symbol of the future, thanks to a showcase renovation that overhauled the bones of the 88-year-old structure, and ongoing efforts to implement ULI’s Tenant Energy Optimization Program (TEOP), the focus of a half-day event in that building in July.

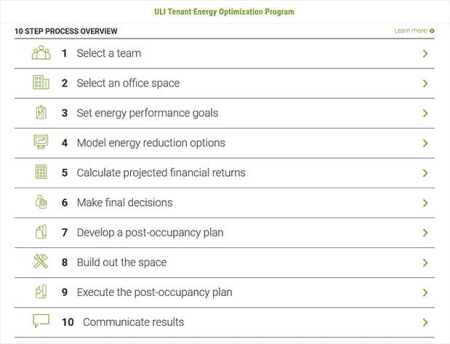

Home to a number of the original TEOP pilot projects, the Empire State Building was a fitting place for attendees to learn about the program’s simplified 10-step approach to making leased spaces more energy efficient and sustainable. In a time when many buildings owners are already working to decarbonize and decrease overall energy use, TEOP provides a framework for leased spaces to increase energy efficiency and sustainability.

Until not too recently, the Empire State Building was a place that everyone wanted to visit but few wanted to work in. Tony Malkin, chairman and CEO of Empire State Realty Trust, noted that the building featured 750 individual suites with an average rent per square foot of around $26 ($280 per sq m). Early signs were not encouraging, he said. “We hired the best people to do this repositioning for us and they came to the conclusion this is never going to be a big tenant building. You’re never going to get great rents and they said to just keep doing what had been done. So we fired them.”

A comprehensive overhaul using the Tenant Energy Optimization Program, developed and championed by Malkin, a ULI full member on a product council, attracted large and prestigious tenants, including LinkedIn, Skanska, Shutterstock, the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Global Brands Group. It also substantially reduced the building’s energy costs, resulting in a peak electric demand of 9.5 megawatts, down from 11.6, resulting in annual savings of $4.4 million—and attracting an Energy Star 87 rating and a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold rating—all while the density of occupancy went up.

Malkin said, “We didn’t add to the electrical supply.” Improvements were achieved “by making the building more energy efficient. By improving the exterior of the building. By redoing 6,514 windows.”

There is only so much a building owner and operator can do, however, before inducing their tenants to adopt better practices. Tenants are responsible for some 40 to 60 percent of energy consumption in buildings, and a variety of speakers pointed to ways TEOP can ensure that tenants accomplish energy reductions. Malkin continued, “Tenants really control what’s going on in the building. We really need to address the tenant spaces.” Empire State Realty Trust proceeded to require TEOP for all tenants (both in the Empire State Building and other properties). This involves slightly greater initial costs, but it is not a noble sacrifice over the longer term. “We end up with tenants paying a little more upfront, but through their savings which we documented they get an average of 25 percent IRR [internal rate of return] on their spaces through savings on electricity.”

Dana Schneider, managing director, energy and sustainability projects at JLL, noted that they initially devised 66 projects for energy reduction, narrowed through study to eight, which resulted in a guaranteed 38 percent annual energy reduction and a three- to five-year payback. “Six of our eight measures are in the tenant space.” There are many facets to that effort: “There’s no silver bullet, we call it silver buckshot.”

TEOP is also a constant process whose most important element is advance planning. Turnover is expected in any office building, and provides constant opportunities to improve design during these natural gaps in tenancy. “Every single space has rolled, is rolling, is being renewed inevitably all the time, so we developed high-performance construction design guidelines.” She attested that applying these measures should not delay the goal completion date for tenant fit-outs in the slightest.

Many elements can be redesigned, including lighting, occupancy sensors, and temperature controls. Then there are elements that require tenant education and behavior change: ensuring that climate controls are used; that printers, computers, and other equipment are turned off when not being used; and that other efficient practices are being observed. “Don’t have a 68-degree setting in the summer. Maybe make it 74. Use your lighting controls—don’t override them. I’ve walked through spaces where the daylight sensors are taped over.”

Schneider stressed the practical financial incentives to TEOP. “There’s an amazing business case. . . . I don’t understand why everybody doesn’t do this.”

Beth Heider, chief sustainability officer at Skanska USA, provided a case for the ease of these processes from one of the Empire State Building’s high-profile recent tenants.

Skanska senior leadership finally consented to the idea of aiming for LEED Platinum certification with the caveat that “it can’t cost any more,” Heider noted. “We have done numerous studies on the business case for greening and we knew that it was going to require an investment, not cost more. It would require an investment, so finally we were able to convince them.”

Work on their Empire State space revealed peculiarities and opportunities. Its age meant that it had operable windows, a relic from before the age of the impermeable curtain wall and an excellent natural heating or cooling expedient. A very considerable core means that all office space is near these windows.

The removal of the building’s original air conditioning (awkwardly installed such that 19 percent of the window area was obscured) and its replacement by under-floor air distribution meant that windows were fully exposed again and ceiling heights increased.

This investment succeeded beyond all expectations, with 57 percent energy savings compared with their Madison Avenue space. Payback on this investment did not take a possible 15 years; it took a mere five. “By the end of our lease, we will have saved $400,000.”

That is not the only benefit. She noted that the first year occupying this space (with a similar employee base as in the previous space), “we took a look at sick leave, and sick leave dropped by 13 to 18 percent.”

Mike Zatz, chief of the market sector group, Energy Star commercial and industrial branch, at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), spoke about the development of the Energy Star for Tenant Space program, and its growth out of earlier whole-building Energy Star programs, with a 100-point scale identical to the larger Energy Star system. This new tenant program, launched in the Energy Improvement Act of 2015, featured two components—one for design and construction, and another for operation.

There are a few general requirements. First is simply estimating the energy use in one’s space. Zatz said, “The value of benchmarking is you see what you start from and what gets measured then gets managed.” Second is metering, to measure actual energy consumption in individual tenant spaces so far as is possible. Third is lighting configuration, as a considerable source of energy. Fourth is use of efficient Energy Star products generally. Fifth is a requirement to share data with management, which can often prove a valuable source of concepts for improvement.

The EPA launched a pilot in 2017 for office tenants. “We were expecting to get maybe 20 participants; we ended up with 140 tenants participating.” Fifty-one of these completed the process and received the new Energy Star for Tenant Space recognition. They also envisioned that this would focus closely on new spaces, but the vast majority were for older spaces, both encouraging and useful in terms of focusing their future efforts.

In many jurisdictions, New York included, technical help and financial incentives are also available. Sophie Cardona, program manager, Commercial Tenant Program, at the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), outlined the considerable reduced technical assistance available.

She pointed to one practical result of this advice: White and Case’s new office space development in 2016, which included innovations such as grouping “all of the teams that worked late on one floor that allowed them to drastically reduce their after-hour HVAC usage.” They reduced their energy use by 39 percent, with a one-year payback of about $385,000.

David Pospisil, business development manager at ConEd, outlined a variety of incentives they offered for Tenant Fit-Out Efficiency. These incentives are based on the “amount of energy saved beyond minimum code requirements” and involve a variety of rebates available for energy-efficient devices.

Many speakers testified to the value of making efficiency in tenant spaces a goal with concrete rewards that could be proclaimed and demonstrated. Heider noted that at Skanska these measures “reflected our brand and market” given that they “embrace sustainability as one of our core values.” However, companies in all sectors can benefit from participating in TEOP, not just those with sustainability and energy efficiency as core pillars of their business strategy.

Malkin observed that “everybody wants a plaque—and there was no plaque for rewarding tenants for doing energy-efficient installation.” That is not the only award, though; the real award is savings, which are accessible to countless tenants.

“Energy efficiency is something which can be afforded by everybody because we all pay the same cost for electricity. You may have different rent, you may have different salaries for your employees, but we all pay the same cost in each of our own jurisdictions for electricity. Therefore, the investment and return formula works for everybody everywhere.”

To learn more about the Tenant Energy Optimization Program (TEOP), visit tenantenergy.uli.org or reach out to Emily McLaughlin at [email protected].