Tax increment financing (TIF) can be a powerful economic development tool. Under the right circumstances, TIF can generate enough funding to make a real difference. And with the right safeguards in place, TIF encourages government and the private sector to form a partnership based on each other’s strengths.

“Without TIF or other government programs, the only redevelopment will be for the rich, by the rich,” says Stephen B.Friedman, a consultant with decades of TIF experience in Illinois and Wisconsin and a member of ULI’s Public/Private Partnership Council. For neighborhoods in need, he continues, “TIF works because government looks the private sector in the eye and puts the public money where the private sector is also willing to put the private money. You have to have a meeting of the minds about what works for the community and for the developers.”

Related: Register for Public/Private Partnerships: Best Practices and Opportunities

Built on a foundation of growing tax revenues, TIF is vulnerable to both national and local economic downturns. Indeed, as the Great Recession spread throughout the United States, TIF districts became weak at just the time they were needed most. Moreover, as local governments cut budgets to the bone, the revenue generated in TIF districts came under close examination. In states where both TIF and education spending depend heavily on revenue from property taxes, TIF’s impact on education became a frequent flashpoint for controversy.

“The recession caused the whole development finance industry to take a hard look at what they are doing,” says Toby Rittner, chief executive officer of the Council for Development Finance Agencies (CDFA). At one extreme,

California Governor Jerry Brown in 2011 ended TIF for redevelopment and ordered the special authorities that managed TIF revenues to close. But most cities and states shared the view of TIF held by Minnesota’s legislature, which expanded a diminished TIF program as part of a 2010 jobs bill.

The hard look produced changes. “We discovered that TIF has a lot of depth,” says Rittner. “Coupled with a comprehensive approach to economic development, it can be used for more than just infrastructure and traditional redevelopment activities, and it can leverage other financing tools.”

TIF originated in an act of policy creativity in California in 1952: federal dollars flowing to remedy what was then called urban blight required a local match. In the subsequent decades, every state in the United States except Arizona has experimented with TIF in one form or another—and then in another and another. As the federal dollars dried up in the 1970s and 1980s, TIF nourished redevelopment. TIF has been exported: pilot projects are underway in Scotland and England, with versions tailored to their tax regimes.

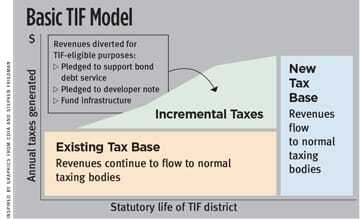

From the developer’s perspective, TIF is just one of many ways to partner with government to share the costs of development. From the government’s perspective, TIF’s distinctive feature is that it provides a means to access new tax revenues to support the creation of these same new revenues, and more. Public investment increases private property values, which increases property tax revenues. Those new revenues can be leveraged to pay for the improvements that attract the private investment, setting up a virtuous cycle of increasing development that pays for itself and increases the tax base.

In the United States, TIF is governed by state law, but implemented by municipal governments. Although this discussion refers to cities, TIF can also be implemented by county governments, economic development authorities, or other municipal governments.

The following hypothetical example illustrates the components of TIF.

River City’s economic development plan aims to transform the city’s vacant industrial waterfront into a mixed-use district of offices, retail space, and housing lining a linear waterfront park. River City designates a TIF district on the waterfront, with a duration of no more than 15 years. The property tax revenue generated by the district at the time of designation becomes the frozen base revenue. The base revenue continues to flow to government coffers as usual.

The “increment” is any property tax revenue generated above the frozen base. Provided there is a spark to stimulate it, the increment grows over time, generating funding to pay—directly or through borrowing—for public investments in the district. River City can create a spark by working with a private developer on a development proposal. The city issues bonds secured by the forecast increment—the increase in property tax revenue expected from the developer’s proposal—to pay for upfront development costs, whether borne by the developer, the government, or both. At the end of 15 years, the TIF district is dissolved and the increment returns to general tax revenues.

Diversity and Complexity

TIF interacts with tax regimes that differ by state. For revenue generation, TIF is most powerful in places with high property taxes. Because states with high property taxes often dedicate those revenues to education, TIF laws that allow access to the school district’s portion of the property tax increment can produce significant revenue. Although many states allow TIF to access retail sales taxes at a district level, sales taxes are relatively weak revenue generators.

Either the public or private sector can take the first step in initiating a TIF district. A community-driven TIF district “means the city is taking a proactive role and making policy decisions about priorities,” says Amanda Rhein, senior director for transit-oriented development at the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority and a member of ULI’s Public/Private Partnership Council. A developer-driven TIF district, however, relieves the city of the need to court developers with an untested plan. A city’s policy culture may favor one approach, but many cities do both. Developers should expect development negotiations to be more intense if they are the ones initiating TIF discussions.

Today, depending on the state, TIF supports everything from expanding affordable housing to attracting manufacturers to industrial zones, including provisions for job training. In some states, TIF must be used solely for public projects, such as infrastructure; other states allow, and even encourage, TIF in support of private development costs, such as those for rehabilitating existing buildings or subsidizing the interest on loans for new construction.

TIF laws include what is known as a “but for” clause—a way of saying that private sector projects that would happen anyway, without support from the increment, are ineligible for the financing. Though a too-literal interpretation of the “but for” clause can unnecessarily restrict TIF’s economic development uses, “there has to be some way of assuring the public that the city is not just giving money away,” says Rachel Weber, TIF expert and associate professor of urban planning and policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “A city should be able to distinguish between ‘what is needed’ versus ‘what would be nice’ to fulfill its economic development goals.”

Cities have options on bearing investment risk. They may use the increment to secure bonds—especially useful for large, upfront development costs. They may also use what is called “pay-as-you-go” financing and expect the developer to secure the credit: the city participates by promising the developer a portion of the increment. Cities may also choose to fund, rather than finance, the endeavor, spending the accrued increment directly on the project.

Developers should not expect 100 percent of the increment to be available. Rittner advises cities to reserve some of the increment to pay administration expenses. Moreover, the amount of need—the financing gap for each project—typically dictates the portion of the increment awarded. In times of scarce private financing, the financing gap may be bigger than the city is able or willing to fill with TIF. Indeed, Rhein notes, “developers often cannot depend on TIF alone; they need to be creative about layering public sector programs—drawing on TIF, but also other tax credit and grant programs.”

Chicago

Shortly after Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel took office in 2011, he fulfilled a campaign promise by convening a TIF Reform Task Force. Advising on a program generating $500 million a year from 163 TIF districts comprising about 10 percent of the city’s property tax base and covering 30 percent of its land area, the task force focused on increasing transparency and accountability. Under Illinois law, over the 23-year life of a TIF district, as long as money is flowing into a district, the city can continue to initiate new projects, increasing the importance of an ongoing process for accountability. In addition to recommending aligning TIF with a multiyear economic development plan and capital budget, the task force advocated establishing metrics to monitor performance of the city’s TIF program.

Among the reforms, the city has inaugurated strategic reviews every five years and in July 2013 unveiled the public TIF Portal, a web mapping tool linked to each district and its associated projects. “The city is becoming smarter in how they give their money away and stricter in terms of financial audits and holding recipients accountable to their promises,” says Weber, a member of the task force. “The city has taken more of an investment mind-set to ensure they are not providing a huge windfall to the developer at the public’s expense.”

Political debate continues in Chicago, especially regarding education spending and whether TIF is still appropriate in the city’s central area, now in its second decade of strong development. “The city is a lot more reticent to do downtown projects,” Friedman observes. “The focus now is on the outer neighborhoods.” In addition, Emanuel in November 2013 issued an executive order requiring annual calculation of the “TIF surplus” that can be returned to the original taxing bodies, including Chicago Public Schools.

Atlanta

Atlanta’s TIF program, known as TAD (for tax allocation district) and run by Invest Atlanta, the city’s economic development authority, has also undergone changes. “The lull during the recession allowed us to reevaluate our program, use it to create jobs, and better align it with citywide economic development efforts,” says Rhein, who participated in Invest Atlanta’s strategic review in 2011.

Historically, Atlanta used TAD for gap financing, funding developers through grants that covered 5 to 15 percent of project costs via bonds backed by the increment. After the strategic review, Invest Atlanta expanded its project evaluation criteria to include job creation and business attraction. New types of projects include building retrofits, facade improvements, and streetscape enhancements. An energy efficiency grant program rewards participants in the federal government’s Better Buildings Challenge.

In Georgia, school districts and county governments join a city TAD at their discretion. School districts have opted to join half of Atlanta’s ten TADs. When school districts join, Rhein explains, “they negotiate something such as payments in lieu of taxes or a lump sum out of the bond issuance.”

In recent years, Atlanta has also begun using TAD funding for major infrastructure projects, such as the Atlanta BeltLine transit and economic development plan, and a downtown streetcar.

California

By terminating redevelopment authorities and their TIF powers, Brown sent a signal that the goal of compact, walkable development at infill locations—and needs such as affordable housing—will have to be met in new ways. Ongoing discussions throughout the state focus on how to replace what was lost with a comprehensive tool kit. ULI’s five district councils in California worked together on potential next steps, and in November 2013 released the report After Redevelopment: New Tools and Strategies to Promote Economic Development and Build Sustainable Communities.

“If California is going to continue to lead on sustainable development and meet the state’s growing needs for affordable housing and infrastructure investment, cities and counties require the authority, legal powers, and financing tools to encourage infill development,” explains Libby Seifel, head of the Seifel Consulting and a member of the ULI report’s working group. Although the governor recently announced support for expanding eligible projects in infrastructure financing districts (IFDs), which can use TIF, Seifel fears “that IFDs alone are too narrow and will not generate enough public investment unless leveraged with other funds. As the ULI report states, California needs a comprehensive set of tools to achieve the state’s environmental, housing, and economic goals.”

Best Practices

To get started on considering TIF, developers should learn the state’s TIF law and the city’s policy culture, and “understand the terms of the city’s boilerplate development agreement before initiating a request for participation,” advises Rhein.

Friedman advises developers to remember, as negotiations proceed, that TIF is “not an entitlement, it’s a gap filler. Be prepared for a complex set of negotiations, the expectation that you will open your business practices to scrutiny, and that a variety of public goals and values will be injected into your project.”

Because to foster a true public/private partnership, the CDFA recommends that the best practices of accountability, transparency, and due diligence apply equally to both partners. This is the best way to guarantee that TIF’s virtuous cycle is optimally achieved.

Sarah Jo Peterson is senior director, policy, at ULI.