Southern Dallas, which was physically and economically separated from downtown after the construction of Interstate 30 in the 1960s, is undergoing a renaissance focused on transit-oriented development (TOD). Dallas-based developers are focused on revitalizing the “wrong side of the highway” with adaptive redevelopment of historic buildings and new construction of hotels, apartments, lofts, offices, restaurants, shops, and entertainment venues.

Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) is America’s longest light-rail system, with 92 miles (148 km) of track and 62 total stations. The southern Dallas area is home to 45 percent of the population but produces only 15 percent of its tax base. Helped by private investments and public financing strategies such as tax increment financing (TIF) districts, southern Dallas TOD areas have welcomed jobs and housing for middle- and lower-income residents by mixing market-rate and affordable housing with amenities and new public investments in infrastructure linked to the light-rail stations.

GrowSouth, a city initiative launched in 2012 by Mayor Mike Rawlings to jump-start investment with infrastructure and capital improvements, has rebranded southern Dallas as “the greatest single opportunity for growth in north Texas,” one of the fastest-growing regions in the United States. Progress is being made: GrowSouth’s 2016 report notes that southern Dallas’s tax base increased $1.6 billion from 2011 to 2015, including many redevelopment projects in several GrowSouth areas of focus, such as the Lancaster Corridor, Greater Downtown/Cedars, and North Oak Cliff.

Lancaster Corridor

One of Dallas’s first GrowSouth projects is Lancaster Urban Village, located seven miles (11 km) south of downtown, on the Lancaster Road commercial corridor across from the VA Medical Center and the DART VA Medical Center station. Developed by Dallas-based Catalyst Urban Development and City Wide Community Development Corporation in partnership with the city, the $30 million, 193-unit mixed-income apartment complex on 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) opened in 2014.

Dallas-based Catalyst Urban Development and City Wide Community Development Corporation, partnering with the city of Dallas, developed the $30 million Lancaster Urban Village across from the VA Medical Center and a DART station in southern Dallas. The completed first phase of 193 apartments and 14,000 square feet (1,300 sq m) of retail and restaurant space drew tenants with amenities unusual for the area, including a business center, fitness center, resort-style pool, and parking garage. (Catalyst Urban Development)

The apartments filled quickly with tenants attracted to amenities unusual for the area—high-end finishes, a resort-style pool, fitness and business centers, a parking garage, and 14,000 square feet (1,300 sq m) of ground-level retail and restaurant space. Capital is being raised for the next phase, a 50,000-square-foot (4,600 sq m) office expansion codeveloped with the adjacent Urban League of Greater Dallas and North Texas. A third phase is being planned with the city for mixed-use development of medical offices, retail, restaurants, housing, and shared parking with the VA Medical Center.

Lancaster Urban Village received half of its construction budget from federal and city programs. Half of the units are affordable and half are market-rate. With no “comparables” in the area, the financing was challenging and took two years to secure, says Catalyst project manager and principal Paris Rutherford. The historically African American neighborhood, now half Hispanic, has many seniors and immigrants. Though fairly stable, it has high poverty and unemployment rates and many dilapidated buildings. But Catalyst saw potential and liked the location next to transit, the hospital, and the Urban League.

“This was an aspirational project, and we tried to show good urbanism,” says Rutherford. The design complements the architecture, materials, and streetscapes of the hospital, the Urban League building, and a Chase bank “so it would read like a master-planned development” to encourage more development, Rutherford says. “The community has really embraced and is proud of the project.” The apartments were fully leased ahead of schedule and beat their pro forma, with many tenants moving in from the neighborhood. Only one-quarter of them actually work at the hospital; the rest commute to work elsewhere via light rail.

The groundwork for the project began in 2008 when the Dallas Office of Economic Development created a TOD TIF district that stretches along the Blue Line rail corridor from North Dallas to one stop beyond the Lancaster station. The funding structure allows for an increment-sharing arrangement in which some projected revenues are passed from higher-income station areas to lower-income areas to subsidize development. Affordable housing is a key part of the TIF-financed projects.

The fact that the project’s market-rate apartments leased faster than the affordable ones “showed a real demand for that in the community,” says Jack Wierzenski, DART director of economic development. “It’s been difficult to get investment around rail stations in southern Dallas to try to turn around disinvestment over the years. We’re trying to get developers to take that step, and projects like Lancaster Urban Village and the Cedars South Side show there is opportunity.”

Dallas-based Matthews Southwest launched the redevelopment of southern Dallas’s Cedars neighborhood 20 years ago with South Side on Lamar, the conversion of a historic Sears warehouse-office complex into 455 residential lofts, 25 artist studios, and 120,000 square feet (11,100 sq m) of office and retail space located one block from the Cedars light-rail station. Above, NYLO Dallas South Side Hotel, a century-old casket factory converted into a luxury urban-loft boutique hotel. (Matthews Southwest)

The Cedars South Side

Travel north on the Blue Line to within a half-mile (0.8 km) of downtown Dallas’s Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center, and you will find the Cedars light-rail station, the epicenter of the two-square-mile (5 sq km) South Side area of the Cedars neighborhood. Filled with stately Victorian homes during the 1870s, the Cedars by the 1920s had become an industrial landscape of factories and warehouses. After the construction of I-30, it devolved into an industrial wasteland valued for its cheap housing and studio spaces for artists and musicians.

The recent rebirth of the area is due in large part to the efforts of another Dallas developer, Jack Matthews, founder of Matthews Southwest (MSW) and best known for building the convention center’s Omni Dallas Hotel. Over the past 20 years, MSW has built a core of more than 2 million square feet (185,800 sq m) in 15 Cedars South Side projects that include residential, commercial, hotel, restaurant, and entertainment spaces.

“The Cedars South Side area is the rock star of TOD, mostly because of its location close to downtown, but also because it had some visionary developers who came in at an early stage,” says Tim Glass, manager of research and information for the Dallas Office of Economic Development. Cedars South Side provided a “chance for the arts and entrepreneurial communities to come together in redevelopment that has created an amazing community and a lot of value.”

In 1997, Matthews bought 17 acres (6.9 ha) of land one block west of the Cedars light-rail station, which opened in 1996. As Mockingbird Station, Dallas’s first TOD, was being developed north of I-30, MSW began working on Southern Dallas’s first TOD. The site at Belleview Street and South Lamar featured five vacant office buildings and warehouses for the 1913 Sears Roebuck & Co. Catalogue Merchandise Center. Matthews wanted to preserve the buildings’ historic architecture and develop a high-quality mixed-use and mixed-income project that would appeal to a racially and ethnically diverse population and provide jobs and opportunities for artists. MSW’s adaptive use did that, turning the 1.1 million-square-foot (102,200 sq m) complex into South Side on Lamar, featuring 455 residential lofts, 25 artists’ studios, and 120,000 square feet (11,100 sq m) of office and retail space.

Matthews began buying more properties near the station. In 2000, he donated three acres (1.2 ha) across from South Side on Lamar to the city to build the Jack Evans Police Headquarters. The $65 million consolidated headquarters, which opened in 2003, improved perceptions of safety and stabilized the neighborhood. In 2008, he developed the Beat Lofts, comprising 76 condominium units in a ten-story building next to the rail station with amenities such as a saltwater pool and spa. During the Great Recession, he developed the South Side Studios, where The Good Guys television show was produced, to “bring in a little sex appeal, excitement, and some high-paying jobs,” he says. In 2012, MSW opened the NYLO Dallas South Side Hotel, a five-story former casket factory redeveloped into a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold boutique hotel with 76 rooms and a rooftop bar and infinity pool overlooking Dallas’s skyline. Mayor Rawlings recognized the hotel as leading the push for southern Dallas to become a growth engine for the region.

As the economy recovered, new MSW market-rate and affordable housing projects have drawn more people and economic development to the neighborhood. Opened last December, the $40 million South Side Flats, codeveloped with Irving, Texas–based TDI Real Estate Holdings, includes 288 luxury apartments, five live/work units, a pool, and 414 parking spaces. MSW is working closely with the development and design team of David Weekley Homes, the Houston-based national homebuilder, on Southside Place, 43 three-story single-family homes located on two acres (0.8 ha) between the Beat condos and South Side Flats. The first homes will be completed in 2017.

Using low-income housing tax credits and other public financing tools, MSW built workforce housing: the $24 million Belleview Apartments, completed in 2014, with 164 units of income-restricted loft housing and 7,500 square feet (700 sq m) of office and retail space. “We believe that you have to have all incomes for an urban neighborhood to work,” says Matthews. “You have to provide housing for restaurant workers as well as executives, and for everyone who wants to live there.”

MSW has also developed, owns, or operates nine South Side restaurants and entertainment venues, including two on South Lamar at the district’s northern gateway: the 91,000-square-foot (8,500 sq m) Gilley’s, with a ballroom and music hall, and the 38,000-square-foot (3,500 sq m) Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, opened in January 2016 with seven theaters and a restaurant.

MSW has developed only 20 percent of the properties it owns in the Cedars district, and plans to further link the neighborhood with downtown via the Rivers, a $400 million housing and retail project on 60 undeveloped acres (24 ha) along the Trinity River in Cedars West. Construction is pending a decision on adjacent sites being considered for a station and infrastructure for a private 240-mile (386 km) high-speed rail line from Houston to Dallas/Fort Worth. The project would be funded by Texas Central Partners—17 Texas families, including Matthew’s—and is expected to begin construction by early 2018.

MSW’s projects have been catalytic for other developers, including Buzzworks founder and former tech-corporate entrepreneur Zad Roumaya, who developed the 50-unit Buzz Lofts condominiums on South Akard, completed in 2007, and is developing the Annex on South Ervay, with 38,000 square feet (3,500 sq m) of live/work, creative, and loft-style offices.

One of the bigger projects in the pipeline is the 100,000-square-foot (9,300 sq m) luxury 1904 Ambassador Hotel. Dallas-based Jim Lake Companies, a developer of the Bishop Arts and Dallas Design districts, will use the existing interior structure to create 100 micro lofts and add amenities such as a pool, a rooftop restaurant and garden, retail spaces, and a basement speakeasy. “The demographic that would rent here would be millennials, as it’s walkable to downtown,” says CEO Jim Lake. Construction will begin in 2017.

A Cedars TIF district created in 1992 and extended through 2022 will provide a projected $23.8 million for projects. In 2015, $6.5 million had been used for 11 out of 20 new projects within the district. The Cedars TIF district’s 2015 assessed taxable value was $105 million, an increase of 22 percent over 2014. Another seven new projects with assessed values of $244 million are located adjacent to the TIF district. The North Central Texas Council of Governments also has helped with $5.5 million in funding for wider sidewalks, lighting, and street trees and landscaping to support walking routes to the light rail.

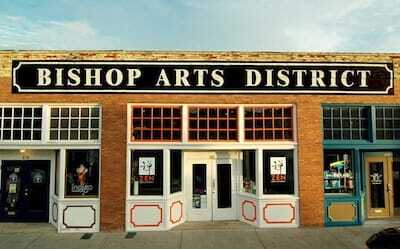

Bishop Arts District

Southern Dallas’s Bishop Arts District is an example of revitalization being a magnet for transit. In 1985, Jim Lake Companies began purchasing circa 1910 properties in the Oak Cliff neighborhood that spanned two blighted blocks of warehouses and artist live/works spaces in a commercial district that had been Dallas’s busiest trolley stop during the 1930s. In the 1990s, the firm began redeveloping the one- and two-story buildings into a thriving and walkable destination-retail street that now boasts over 60 independent businesses—boutiques, art galleries, and 25 restaurants, bars, and coffee shops.

Factors that created synergy for the district include zoning changes in 1999 that allowed for more restaurants and shops and the city’s 2000 investment of $2.6 million in street improvements—wider sidewalks, street lighting, street trees, and landscaping. Jim Lake Companies installed the district’s distinctive patios, alley paving, murals, string lights, and custom signage. After decades of success but without transit, the district was reconnected to downtown Dallas on August 27 with a DART extension of the $50 million Dallas Streetcar.

Like many successful redevelopment areas, Bishop Arts has become something of a victim of its own success, with traffic and retail parking overflowing into nearby residential areas, says Pamela Stein, executive director of ULI North Texas. “The newly opened street car, which is free to ride and will operate until midnight,” says Stein, “is expected to help Bishop Arts continue to thrive without the negative impact of too many cars competing for too few spaces.”

As one of GrowSouth’s focus areas, the Bishop Arts District is growing south five blocks along Bishop Avenue to Jefferson Boulevard, which is being redeveloped as a “model Main Street” for southern Dallas. Jim Lake Companies’ Jefferson Tower—a redevelopment of a 1928 medical office building into 110,000 square feet (10,200 sq m) of offices, 18 live/work lofts, and viewing decks—opened here earlier this year. Ground-floor retail spaces include local sole-proprietor coffee shops, cafés, and a brew pub.

Kathleen McCormick, principal of Fountainhead Communications in Boulder, Colorado, writes frequently about sustainable, healthy, and resilient communities.

![Western Plaza Improvements [1].jpg](https://cdn-ul.uli.org/dims4/default/15205ec/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1919x1078+0+0/resize/500x281!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fk2-prod-uli.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Fbrightspot%2Fb4%2Ffa%2F5da7da1e442091ea01b5d8724354%2Fwestern-plaza-improvements-1.jpg)