When the Field Building on Chicago’s LaSalle Street opened in 1932, it was a technological and architectural marvel, with high-speed elevators, drinking fountains, and even air-conditioning, a first for the city. Built during the depths of the Great Depression, the 43-story office tower represented a huge risk for its developer, Chicago tycoon Marshall Field III, but it ranked as the city’s tallest building for more than two decades.

Nearly a century later, the 1.3 million-square-foot (120,774 sq m) art deco landmark is a pioneer of a different sort. It’s part of bold experiment by Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot to revitalize the city’s historic LaSalle Street financial district, which has fallen on hard times after the departure of its biggest banks and the rise of hybrid work that has emptied out office buildings across the country.

Last month, Lightfoot named the Field Building and two other office towers nearby as the first to make the cut for LaSalle Reimagined, a city initiative to convert millions of square feet of vacant office space into apartments. The city is offering developers tens of millions of dollars in city subsidies to finance the conversions, with a hitch: They must offer 30 percent of their units at below-market rents for tenants with low or moderate incomes.

If the plan works, it could bring new energy to the Chicago Loop and diversify a part of the neighborhood that includes no affordable housing currently.

“Providing those housing opportunities will be key in our mission to reimagine Lasalle Street as a mixed income, mixed-use community, as well as our mission to restore equity,” Lightfoot said at a March 28 event where she announced the three projects. “In these buildings are people who work, who clean, who make sure that the buildings are beautiful and lustrous. Shouldn’t they also have the opportunity to live downtown within walking distance of their workplace?”

Cities across the country are grappling with the same problem in the post-pandemic era: What to do with all their empty downtown office space. With more employees working remote or hybrid work schedules since the arrival of the pandemic, office vacancies have soared the past few years, recently hitting a record 22.4 percent in downtown Chicago, according to CBRE. A study by Cushman & Wakefield forecasts that U.S. office density per employee will drop to 165 square feet (15.33 sq m) per employee within eight years, down from 189 before the pandemic. Cushman estimates that 25 percent of all U.S. office inventory will become functionally obsolete by then, while another 21 percent will require upgrading or repurposing.

Government leaders across the country are exploring different solutions to the problem, but many see residential conversions as the best option amid a strong rental market and shortage of affordable housing. A California lawmaker has introduced a bill that would provide grants to developers that redevelop empty office space into housing. The District of Columbia has created a program that would provide property tax abatements for residential conversions. In New York, Mayor Eric Adams has proposed an easing of regulations to encourage more developers to turn unused office space into housing.

LaSalle Street began emptying out even before the pandemic. Bank of America, which leased 827,000 square feet (76,831 sq m) in the Field Building, its longtime home at 135 S. LaSalle St., decided to move to a new office development on the Chicago River back in 2017. The following year, BMO Financial Group, agreed to leave its Chicago headquarters on LaSalle Street to anchor a new 50-story tower near Union Station in the West Loop.

The departures left gaping holes and pushed the buildings into loan trouble. Several other vintage Loop office towers are facing foreclosure after tenant departures as well.

It will take creative minds, determination, and lots of money to redevelop all the excess office space into something useful again. The Lightfoot Administration is offering huge financial incentives to developers for its affordable housing quid pro quo. The developers of the first three LaSalle Reimagined projects are seeking a combined $188 million in tax-increment financing from the city, subsidies that they say make the developments financially feasible.

The money will allow them to convert office space in the three buildings into 1,000 apartments, with 318 units set aside for residents earning an average of 60 percent of area median income. That’s $50,040 for a two-person household. The 30 percent affordable requirement exceeds the 20 percent threshold mandated under Chicago’s inclusionary zoning ordinance, which applies to developers that seek zoning relief for big projects.

Developers say they need TIF subsidies to offset the high cost of converting office space into residential and to make up for the revenue they will lose by renting so many apartments at below-market rents.

“Without TIF, our project would likely not have affordable housing,” said Quintin Primo, chairman and CEO of Chicago-based Capri Investment Group, co-developer of one of the former BMO buildings just east of LaSalle. “We couldn’t afford it.”

Capri and its partner, Chicago-based Prime Group, plan to convert the property at 111 W. Monroe St. into a 228-room hotel and 349 apartments, 105 of them affordable. The residential portion would cost $180 million, about $516,000 per unit, with a TIF grant covering $40 million of the tab.

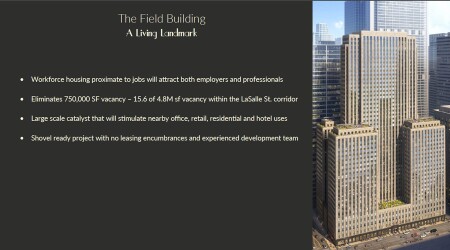

On the south end of the same block, Chicago-based Riverside Investment & Development and AmTrust Realty of New York are teaming up on an even bigger project at the Field Building. They plan to convert the lower floors of the building into 430 apartments, setting aside 129 as affordable. TIF funds would cover $115 million of the total $258 million project cost.

Given the big outlay of public dollars, some observers have questioned whether the city could get more bang for its buck by investing the money in other projects. The $188 million in TIF subsidies for the three projects works out to $591,000 per affordable unit.

But city officials say it’s worth the cost to bring more socio-economic diversity to the Loop. Chicago is one of the most segregated big cities in the country, and Lightfoot has made housing desegregation a key priority of her administration.

Proponents also point out that without financial incentives for developers, some Loop buildings would sit empty for a long period of time, impeding LaSalle Street’s turnaround. Incentives will speed up its recovery.

“This isn’t something where we’re trying to rain money down on ourselves,” said Riverside CEO John O’Donnell. “It’s about getting it done.”

Conversions of outdated office space into housing isn’t a new idea, nor do they always require government help. In Chicago, a development venture recently converted the historic Tribune Tower near the Chicago River into high-end condominiums.

LaSalle Street’s old age is an advantage because many of its vintage office buildings can qualify for historic tax credits or property tax abatements to make the numbers pencil out. Riverside, for instance, plans to finance the Field Building conversion with $34 million in historic tax credits.

The big question for LaSalle Street now is whether Lightfoot’s successor, Brandon Johnson, who was elected on April 4, will embrace LaSalle Reimagined. The City Council still needs to approve the TIF subsidies for the three conversions, and proponents of the initiative are pushing for the city to finance more.

The mayor-elect, a progressive, has offered general support for the program, though he has raised concerns about providing subsidies for projects that don’t need them. A Johnson spokesperson didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The change in leadership could alter the direction of the initiative, but O’Donnell and Primo believe the argument in its favor is so strong that Johnson would be crazy to scrap it.

“This is a very neat, tidy thing,” Primo said. “Who could argue about bringing affordable housing to the central business district?”

![Western Plaza Improvements [1].jpg](https://cdn-ul.uli.org/dims4/default/15205ec/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1919x1078+0+0/resize/500x281!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fk2-prod-uli.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Fbrightspot%2Fb4%2Ffa%2F5da7da1e442091ea01b5d8724354%2Fwestern-plaza-improvements-1.jpg)