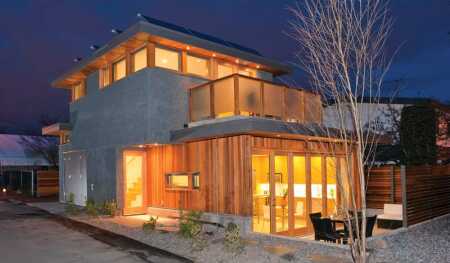

Rising property values and taxes, along with changing demographics, have stimulated growth in PAD demand in both cities and suburbs. One of the first solar laneway house PADs in suburban Vancouver, British Columbia, was built by Lanefab Design/Build as infill on an existing 50-by-125-foot (15 by 38 m) residential lot. It is 1,050 square feet (98 sq m) with one bedroom and two bathrooms built for the owners of the existing main house. (Lanefab Design/Build)

One of the large impacts of single-use, single-family detached zoning has been to severely shrink the supply of accessory dwellings, which often were created in or near primary houses. Detached single-family dwelling zones—the largest housing zoning category—typically preclude more than one dwelling per lot except under stringent regulation, and then only in some jurisdictions.

Bureaucratically termed “accessory dwelling units” that are allowed by some jurisdictions may encompass market-derived names such as granny flats, granny cottages, mother-in-law suites, secondary suites, backyard cottages, casitas, carriage flats, sidekick houses, basement apartments, attic apartments, laneway houses, multigenerational homes, or home-within-a-home. To simplify the jargon for this article, we use the common and colloquial acronym PADs, which stands for “private accessory dwellings,” noting where neccessary detached, garage, basement, attic, or carriage unit locations.

Accessory units, ranging in cost from under $50,000 to more than $400,000 and in size from about 300 to 1,000 square feet (28 to 93 sq m), are complete living units with kitchen, bathing, living, dining, and sleeping components. They are not room rentals and do not transform a house into a boarding house. They are private and have their own entrances; they are accessory to, or in, the main house.

On one 33-by-122-foot (10 by 37 m) single-family lot, Lanefab Design/Build recently constructed three units including a 1,900-square-foot (177 sq m) remodeled house, with a 900-square-foot (84 sq m) basement suite, and a 780-square-foot (72 sq m) laneway house. That boosted the density to over 32 units per acre (80 per ha), higher than that of many garden apartment complexes. (Lanefab Design/Build)

Changing trends in demographics, economics, immigration, and cultural preferences alter market behavior. The net effect of recent demographic changes is that we have millions of single-family detached houses, which have more than doubled in average size since 1950, with about a third fewer—and older—people living in them. Not only are the houses larger, but so are the lots on which they sit. If PADs can be added in appropriate scale and number, existing housing, zoned land, and current infrastructure could be efficiently used to increase housing supply and to stabilize or even reduce housing prices. Moreover, since PADs are by definition smaller than existing dwellings, they will attract both younger and older residents who will enrich the intergenerational compostion of both urban and suburban communities.

Detached single-family dwelling zones were widely adopted during the post–World War II period when households transformed from extended to nuclear families. In 1950, more than 87 percent of households contained a husband and a wife, and 58 percent had children under 18 living at home. Suburban land was inexpensive; homeownership was subsidized by federal policies; and the Interstate Highway Act of 1956 opened wide swaths of developable land. In 1950, less than half of homes were owned, compared with two-thirds today. Now, married households represent less than half of all households, and those with children represent under a quarter. Single-person households increased from less than 8 percent in 1950 to almost 30 percent today. Moreover, about 124.6 million Americans were single in August 2014, accounting for 50 percent of those who were 16 years or older, according to data used by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, so the market for single-person households is likely to continue to increase.

The size of the average single-family house in 1950 was only 983 square feet (91 sq m), but it almost tripled to over 2,679 square feet (249 sq m) by 2013, according to the National Association of Home Builders. Yet, average household occupancy has declined about one-third from 3.7 to only 2.5 per residence. The American Enterprise Institute found that the square footage of living space per person in the median-size new home has almost doubled since 1973 from 552 to 1,055 square feet (51 to 98 sq m).

While typical postwar city lots measured about 5,000 square feet (465 sq m), the median size now is almost double at 8,900 square feet (827 sq m). Since the average plus-or-minus-2,000-square-foot (186 sq m) house occupies a footprint of only about 1,000 square feet (93 sq m), up to 90 percent of the average lot might be available for accessory buildings. So the outstanding detached housing stock reveals larger houses with fewer occupants on larger lots, largely open. PAD proponents eye these larger houses and larger lots to create both internal and detached PADs for multiple markets in cities and suburbs.

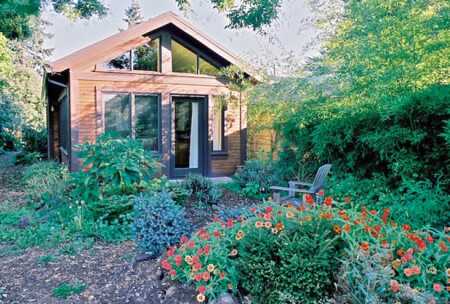

Because Portland does not have an owner-occupancy requirement, one owner chose to build an external PAD on one of her rental properties to generate income for retirement. She spent $200,000 to build a 642-square-foot (60 sq m) unit built to specifications that also would give her the option of moving into it in retirement. (Beverly Scott)

Baby Boomers

While there has been some growth of older populations within cities, more than three-quarters of those older than 50 live in suburban or non–metro areas in single-family houses on larger lots.

The current configuration of detached single-family houses in cities and suburbs is not well adapted for older single people. This imbalance has given new impetus to homeowners to expand the PAD supply. About 10,000 U.S. baby boomers will turn 65 every day for the next 20 years. While many want to downsize to smaller units, a November 2010 AARP study found that three-quarters of respondents over the age of 45 strongly preferred to age in place in their own homes. But for many of them, retirement assets are less than adequate to maintain their lifestyle.

One strategy is to build a PAD to generate supplemental retirement income to remain in their homes. In many markets, PADs can generate between $1,000 and $2,000 in monthly rent. And with the growth of options like Airbnb, PAD rentals could generate from $75 to $250 per night while adding additional capital value to the underlying house.

Another strategy for boomers wishing to age in place is to build a new, single-level detached PAD on their own property intending to first rent it and then eventually downsize into it when it becomes more difficult for them to navigate stairs. Some boomers wish to reverse that plan and use the PAD as a place in which to house a caregiver to help them remain in the primary house.

Age Integration

Daycare, elder care, seniors’ independent living housing, congregate care, assisted living, memory care, skilled nursing, and continuing care are not only terms codified into land use planning, legislation, finance, and regulation; they also represent new institutions that have been developed, segregated, and isolated from other types of housing. Many boomers cannot afford to pay market rents of up to about $6,000 per month for independent housing or institutional care—even if they wanted such living arrangements—and many boomers prefer to live in age-diverse communities.

While some developers of seniors’ housing are building new facilities in more transit-oriented urban areas, even in connection with universities for greater stimulation and amenities, these large projects are still segregated by age, income, and health condition. Among boomers who want to age in place, many want to be in a more age-diverse intergenerational setting near families with children. They can remain in their houses by creating smaller PADs that would be rented to younger people, providing age diversity while generating income.

Other boomers want to travel more while having someone responsible for their house while they are gone, yet generate income while doing so. Some boomers have small businesses they are able to downsize and move to their property, saving the expense of office rent. And many retired boomers want to spend more time with their children and grandchildren but have inadequate facilities to house them for extended stays.

Because extended families may be geographically scattered, large numbers of more affluent boomers travel to spend time with their adult children and grandchildren. Rather than buying or renting an urban condominium near their offspring, it can be far more economical for them to finance the construction of a PAD on their children’s land to use for extended stays or even as a future residence. Such a strategy can reduce parents’ living expenses while adding capital value to their children’s property as a gift.

Naomi Cole, who researched this article, and her husband bought a house and converted its garage into a relatively inexpensive $45,000, 375-square-foot (35 sq m) PAD with design knowledge, salvaged materials, and sweat equity to live in while renting out the main house to help pay the mortgage. Later, they moved into the main house and eliminated the rent for her husband’s downtown office while renting the PAD. (Jenny Tweto-adu)

Echo Boomers

Another population segment stimulating the building of PADs is the children of baby boomers. A Pew Research Center study reports that one in four young adults between the ages of 25 and 34 was living with parents in 2012. Pew also found that 57 million Americans, or 18 percent, lived in multigenerational households in 2012—double the number in 1980. Reduced incomes, later marriage age, and extended schooling are other factors driving this boomerang trend.

The increase in immigration has helped change the composition of the population. Changing ethnic populations and the increasing number of larger immigrant families have fueled the trend toward multigenerational living. About one in four Asian Americans, Hispanics, and African Americans lived in multigenerational households in 2012, the Pew Research Center found. In Vancouver, British Columbia, custom design-builder Lanefab reports that nearly three-quarters of its PAD business, its major specialty, is from second-generation Asian or mixed-race couples.

Developers can best understand the emerging market for PADs by tracking what individual homeowners have done acting as their own developers.

Strategies for Creating PADs: Conversion

The most common and least expensive way to create a PAD is through the conversion of existing space within a house. Attached garages are particularly popular since they are separated from existing living areas, are fully accessible at grade, can accommodate a living unit of approximately 400 to 500 square feet (37 to 46 sq m), and normally contain the entry points for house infrastructure including electrical panels, plumbing lines, water heaters, HVAC equipment, and cable and telephone communications panels. They usually have an exposed structure that is easy to insulate and finish. On-site parking is already provided in garages’ driveways and aprons. A garage PAD conversion might cost only $40,000 to $60,000. Some garages have lofts or second stories, often built as bonus rooms, which can be converted to PAD carriage house units, while still maintaining private access, even though it requires stairs.

A variation on an inversion strategy that permits new construction in close-in locations is to transform an existing small house into a PAD and then build a newer, larger house on the same lot. Caleb and Tori Bruce transformed a 450-square-foot (42 sq m) bungalow in Eugene, Oregon, into a PAD and then hired an architect to design and build a very modern house as the primary. (Caleb & Tori Bruce)

Basements are more difficult to convert to PADs than garages because access is more limited, unless they are daylit basements on sloped lots. Sewer lines may not be low enough to allow for additional plumbing without pumped removal. Ceiling heights are more limited, as is daylight. However, to encourage conversion of basements, Vancouver changed its regulations to allow ceiling heights as low as 6.5 feet (2 m). In some locations, however, basements are spacious, separated from the main house, and underused. Some have already been finished and may contain bathrooms and bars that can easily be converted to kitchens.

Like garages, attics have exposed structures, are normally as large as the footprint of the house, can be retrofitted with infrastructure, and can be lighted with skylights. But private access is more difficult to provide for an attic PAD, and stairs may limit the market.

Another physical strategy for the conversion of existing space is what is sometimes called a carve-out. Existing bedrooms, family rooms, guest rooms, playrooms, or servants’ quarters can be segregated from the main house and upgraded with a new kitchen and bathroom. Since such spaces are more integrated with the main house and are likely to have only internal access, such PAD conversions are more appropriate to reversionary situations, in which—often for economic or medical reasons—children or parents are reverting to the single-family detached houses in which they were raised or where they had their children. Whether they are aged parents or boomerang adult children, they are likely to desire some degree of independence. Privacy also is highly valued by unrelated single adult friends who choose to live close together to share the burdens and benefits of single-family detached or attached living.

Many houses have wings that can be effectively separated to enhance independence. The Usonian houses of Frank Lloyd Wright were based on a wing design, and the ubiquitous suburban ranch houses that followed featured wings. New wings can often be added at lower cost than detached PADs and may ensure outdoor accessibility. Larger bedrooms can accommodate additional bathrooms.

Teague Douglas, a 30-year-old green building and energy efficiency professional, found a 6,450-square-foot (600 sq m) lot (center left) in Portland with a 950-square-foot (88 sq m) one-story bungalow and a 320-square-foot (30 sq m) shop. She bought it in 2012 for $162,900 with a plan to rent it out for about $1,400 per month while building a PAD of 550 square feet (51 sq m) with loft in which to live herself. (Google Earth)

Reversion

Coupled with the physical strategy of conversion is the demographic-driven strategy of reversion to parents’ lots. This is not being done by boomerang adult children but by young working couples who are priced out of homeownership. In Vancouver, where land values and property taxes have risen sharply, many young couples are building detached PADs on their parents’ lots, financing them by arranging a home equity loan against the parents’ property. With today’s low interest rates, mortgages can be more affordable than rent, and construction costs, without land, are lower than the price of equivalent-sized condominiums. Custom design-builder Lanefab in Vancouver reports that about two-thirds of its clients are following this strategy.

Inversion

Yet another social strategy has triggered demand for new PADs. Some homeowners want to downsize their use of space and occupy just a single level of their existing single-family house. In such cases, a detached freestanding PAD may be a desirable alternative, since it can be designed for the specific needs of the owner. With no need to pay for land, and with the increased income generation from renting their larger house, rather than the smaller PAD, the homeowners may cover the cost of construction while increasing the underlying value of the property. Such a strategy can be particularly useful for those who own second homes in resort areas yet want to maintain a presence in the cities in which they have spent much of their adult lives.

Diversion

A different strategy for some homeowners is to divert traditional house expansion to a separate PAD that can accommodate family growth. Building a separate cottage PAD can function as an office, a workshop, a playroom, and a guest room. But it adds flexibility for different future living arrangements, such as for teenage children or older parents, and to generate short-term rental income later.

Another strategy for boomers wishing to age in place is to build a single-level PAD on their property to first offer for rent and then eventually downsize into. Bruce Nelson and Carolyn Matthews funded a $260,000, 640-square-foot (60 sq m) PAD in Portland by tapping inheritance and retirement funds. (Carolyn Matthews-Bruce Nelson)

First Acquisition

Pressed by the rising cost of housing, high levels of student debt, tighter credit restrictions, and relatively stagnant incomes, younger singles and couples are finding it difficult to become first-time homebuyers. A new PAD strategy finds such people buying older, less expensive houses on slightly larger lots, converting a portion of the house to a PAD, often with sweat equity, and then renting either the PAD or the main house to help pay for the mortgage.

For example, Teague Douglas, a 30-year-old green building and energy efficiency professional, found a 6,450-square-foot (600 sq m) lot in the Cully neighborhood of Portland, Oregon, with a 950-square-foot (88 sq m) one-story bungalow and a 320-square-foot (30 sq m) shop. She bought it at the tail end of the recession in 2012 for $162,900 with a plan to rent it for about $1,400 per month while building a detached PAD of 550 square feet (51 sq m) with a loft in which to live herself. She financed its $75,000 cost with a formal, interest-bearing loan from her father. If circumstances change, she might do an inversion—move into the main house and rent the PAD for about $1,000 in the current market. Her $238,000 capital cost is still below the reported $329,000 median home price in Portland, and she may generate about $2,400 in gross monthly rent to help pay the mortgage.

Another example is Naomi Cole, the graduate student researcher of this article who, with her husband, language instructor Joe Wachunas, bought a 1,672-square-foot, 1987-vintage ranch house on a 5,000-square-foot (465 sq m) corner lot in Portland’s close-in Overlook neighborhood with an attached garage for $235,000. They then converted it for $45,000 into a 375-square-foot (35 sq m) PAD, taking advantage of their design knowledge, salvaged materials, and sweat equity to create their living space while they rented out the main house to help pay the mortgage. Later, the couple reversed the process—moving into the main house while renting the PAD to a tenant.

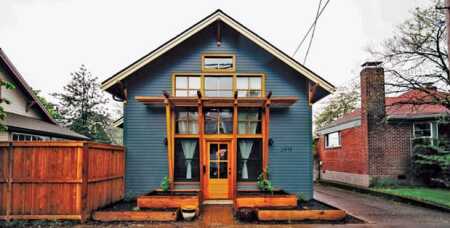

Another young couple without children, James Michelinie and Kyra Routon, bought a 1,700-square-foot (158 sq m) house for $317,000 in 2012 on an alley corner lot in Portland’s Alberta neighborhood and built a 650-square-foot (60 sq m) detached PAD for $90,000. Upon completion, an appraisal increase of $150,000 enabled the couple to refinance the house and PAD, into which they moved, with payment of debt service assisted by rent from the larger primary house. Similar three-bedroom, two-bathroom houses in the area generate market rent between $2,000 and $2,500.

A young couple without children, James Michelinie and Kyra Routon bought a house on an alley corner lot in Portland’s Alberta neighborhood, built a 650-square-foot (60 sq m) PAD for $90,000 plus sweat equity in the form of a design by Routon’s architect father. When the PAD was completed, sweat equity turned real with an appraisal increase of $150,000 that enabled the couple to refinance, with payment of debt service assisted by rent from the larger primary house. (James Michelinie-Kyra Routon)

Regulation

Despite growing demand for PADs, widely varying local regulations tend to make PAD development a one-off undertaking with the single-family detached homeowner in the position of sole developer who must not only hire an architect and a contractor but also navigate the regulatory hurdles, with limited assistance. It can be more complicated than building a new custom-designed house.

Some cities treat the PAD as a new house and apply systems development charges (SDCs) that can exceed $10,000 to $15,000 per unit. To stimulate new development during the Great Recession, Portland waived its SDCs, a waiver that extends until July 2016. This change, along with more liberal size requirements relative to the primary dwelling, unleashed construction of more than 600 PADs in four years. Some cities require the owner to live in one of the units, have at least one additional off-street parking space, and have separate utility meters. PAD size restrictions vary widely and may range from about 600 to 1,000 square feet (56 to 93 sq m). Many cities tie them to a percentage of house size—40 to 75 percent is common, up to 800 square feet (74 sq m) maximum—or to lot size. In Vancouver, for example, the cap is 16 percent of overall lot size.

Vancouver is the most progressive North American city in the movement to increase PAD density. Two PADs per property—one internal PAD and one detached PAD—are allowed in over 90 percent of the city. If the PAD is on an alley, and the site is at least 32 feet (10 m) wide, owners can build what is called a laneway house that can be rented with no on-site owner-occupancy requirement. More than 1,100 have been built since 2009. On one 33-foot-by-122-foot (10 by 37 m) single-family lot, Lanefab recently constructed three units including a 1,900-square-foot (177 sq m) remodeled house, with a 900-square-foot (84 sq m) basement suite, and a 780-square-foot (72 sq m) laneway house. That boosted the density to more than 32 units per acre (80 per ha), higher than that of many garden apartment complexes.

Vancouver requires separate utility meters, sewer and water connections, addresses, building permits, and SDC charges, all of which can cost as much as $20,000. Despite such requirements, substantial increases in both density and affordability—with impacts far lower than those from larger-scale multifamily development rezoning—are beginning to occur. Approximately 60 percent of all detached homes built in Vancouver between 2000 and 2010 included a secondary suite, according to a city of Vancouver report. There are at least 25,000 secondary suites in the city’s single-family zoned areas.

In Victoria, British Columbia, detached PADs are called garden suites; the local government allows them in the backyard in a single-family house zone. But if there is a garden suite on the lot, the city does not also allow a secondary suite to be created in the main house. Portland is considering permitting both an internal PAD and an detached PAD on each lot.

Vancouver also allows secondary suites within existing multifamily condominiums. Typically, the configuration is a two- or three-bedroom unit in which one of the bedrooms is expanded to include kitchen and bathing facilities and opens privately onto a common corridor as well as into the primary unit. (See “Secondary Suites,” Urban Land, May 2007.) The effect of these policies is to disperse and increase the rental housing supply, with lower operating and management expenses, in a manner that also provides income to the owner to help pay the mortgage, while preserving maximal flexibility for future use.

U.S. regulation has begun to change in a manner to encourage consideration of PADs, but it does not approach Vancouver’s standards. California enacted a statute that requires local communities to consider second units, at least ministerially. But it gives broad authority to cities to regulate second units and to prohibit the development of second units in single-family or multifamily zones. Some cities, such as Santa Cruz, have encouraged the development of second units by establishing preapproved design prototypes. But in many cities, SDC and water fees; building and planning code setback requirements; and limitations on lot coverage, design, massing, size, occupancy, and parking tend to be more restrictive than permissive.

PAD restrictions are legion because PAD permits are based on limited exceptions to single-family zones, the bedrock of single-use zoning. But code definitions of family are based on traditional norms, typically “an individual or two or more persons who are related by blood, marriage, or legal adoption living together.” But ongong demographic change can wreak havoc on traditional norms.

More widespread PAD development can help adapt today’s vast quantity of underused housing and land to modern demographic and financial realities, making housing more affordable, intergenerational, and diverse.

William P. Macht is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University (PSU) in Oregon and a development consultant. Naomi Cole, a graduate of the PSU Center for Real Estate, undertook extensive research for this article. She works in green building and energy efficiency and is also a developer, owner, and occupant of a house with a garage PAD. Her unit, and other Portland case studies, are featured by Lina Menard at www.accessorydwellings.org.

![Western Plaza Improvements [1].jpg](https://cdn-ul.uli.org/dims4/default/15205ec/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1919x1078+0+0/resize/500x281!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fk2-prod-uli.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Fbrightspot%2Fb4%2Ffa%2F5da7da1e442091ea01b5d8724354%2Fwestern-plaza-improvements-1.jpg)