For anyone who assumes that e-commerce has relegated shopping centers to the same elephant’s graveyard where typewriters and rotary telephones languish, a recent announcement from L.L.Bean may come as a shock. The 103-year-old, Maine-based catalog and online retailer, which operates 26 full retail stores and ten outlets in a dozen states, is planning to nearly triple the number of its brick-and-mortar locations to at least 100 by 2020.

“We’d like to get into as many markets as possible,” says Ken Kacere, senior vice president of retail. Physical stores, rather than being obsolete, have become a critical part of the company’s “omnichannel” retail strategy for getting Americans to buy its boots, tents, and other outdoors-oriented products, he says.

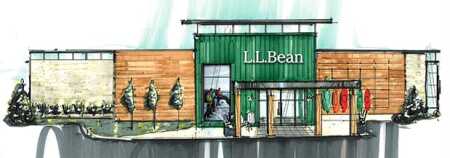

Although the natural light, barn-board, and earthtone decor in the new L.L.Bean stores will create a rustic ambiance that harks back to a simpler time, the underlying design is—in essence—a prototype for a new, cutting-edge style of selling that merges the electronic with the tangible into one persuasive experience.

Customers who venture into the new stores, most of which will have 15,000 square feet (1,400 sq m) of space, will not see quite as many products on the shelves as they might in the company’s bigger, older locations. However, they will be able to order the entire line through an app that they can install on their smartphones, or they can order through iPads located throughout the wifi-enabled premises.

Also, they can interact more with the merchandise at the store by using features such as touchscreens that explain how to assemble a tent that is on display. Such features are part of a museumlike “curated” educational experience. Shoppers also will be able to sign up for lessons in kayaking or fly-fishing through L.L.Bean’s Outdoor Discovery Schools, and they can embark on the trips right from the premises.

“In an hour and a half, we can teach you how to kayak, put you on the water, and get you back to the store,” Kacere says. “It’s all about providing customers with a chance to learn a new outdoor activity or learn more about one they’re already doing. You can’t do that in a catalog or on a website.”

Though Kacere is reluctant to portray L.L.Bean as a trendsetter, it seems as if the venerable brand is at the forefront of retail’s latest evolutionary stage.

“In an hour and a half, we can teach you how to kayak, put you on the water, and get you back to the store,” Ken Kacere says.

There was a time—just a few years ago—when business publications were running headlines such as “Is Online Shopping Killing Brick-and-Mortar?” Moreover, prognosticators were noting the rapid demise of whole segments of bookstore, electronics, and video-rental chains that were being wiped out by competition from the likes of Amazon and Netflix. Even retailers that survived the initial digital thinning of the herd feared a phenomenon called “showrooming”—consumers armed with smartphones roaming their aisles, trying out products, but then shopping online to find a better price and make their purchase.

Now, though, in addition to L.L.Bean, a number of newer, digital pure-play retailers have moved to develop physical locations as well.

Women’s activewear retailer Athleta, for example, opened its first physical store in Mill Valley, California, in 2010. Since then, Athleta has grown to 105 locations in 29 states and the District of Columbia. Upscale men’s clothier Bonobos has opened 17 “guideshops” across the country that give customers the opportunity to make appointments to try on its wares; the firm reportedly plans to open 30 more stores by the end of 2016. Warby Parker, an online designer eyewear retailer, and Birchbox, a beauty products seller, are among other online retailers that have opened stores as well.

Experts say the nascent clicks-to-bricks movement has important implications for commercial real estate—from developers who may need to create more of the mixed-use lifestyle centers that Kacere says are preferred locations for the new stores, to architects and designers who increasingly will be concentrating on using smaller retail spaces in very different ways from today’s norm.

Jesse Tron, an official with the International Council of Shopping Centers, sees the shift as invigorating. “It totally flips the negative from ten years ago into a tremendous opportunity,” he says. “Omnichannel shopping is changing the landscape of retail. There’s more flexibility with the format. You may have a smaller footprint, but more retailers. It’s about gaining tenants, and using the space differently and viewing the physical in a new way.”

Enduring Bricks and Clicks

Retail analysts and consultants say the clicks-to-bricks evolution is driven, in a sense, by the same rationale that led both catalog sellers and traditional retailers with a primarily physical presence to migrate to the web over the previous two decades. At some point, continued growth usually requires expanding the number of sales channels. But in addition, brick-and-mortar retail—despite the body blows inflicted by Amazon and other online merchants—never really went away.

According to a 2014 report by management consulting firm A.T. Kearney, 90 percent of retail sales are still made in physical stores, and 95 percent of sales go to retailers that have both an online and a physical presence. “There are product categories—jewelry and wristwatches, for example—where people really prefer to touch and feel the goods,” says Kevin Meany, chief executive of BFG Communications, a South Carolina–based marketing consulting firm.

In addition, physical and digital commerce increasingly have blended together, says Carol Spieckerman, president of Newmarketbuilders, a San Francisco–based retail consulting firm.

“There’s really no such thing as a brick-and-mortar retailer anymore,” she says. “They all have an online presence, and the distinctions are becoming increasingly irrelevant. There was a brief moment when primarily physical retailers were in a state of panic. But then they realized that their locations are a critical link to digital business, and [those locations] give them an advantage over pure-play digital sellers.”

Having physical locations, for example, gives online customers a place to pick up their orders without having to rely on a parcel service leaving packages on their doorsteps, and it makes returns—a major headache for both customers and retailers—far easier.

Retailers also have realized that though the rise of e-commerce has changed how people shop, the result is different from what was initially expected—in part because of technological advances. The advent of smartphones, for example, has freed customers from having to sit down at the computer to shop online or to do comparative research. Instead, as a 2013 Google survey found, eight out of ten smartphone owners use their devices inside the store.

“Originally, what retailers feared was that people would come and look at the product in their stores, then buy it on Amazon,” Tron notes. “But we’ve found that the inverse is really the norm. Instead of exploratory shopping trips, people now are doing research online, and finding out most of the information they need to make a purchase. But they still need a touch point with the product. When they come in, they’re focused. They interact with it, try it on, and they’re ready to buy.”

The Omnichannel Look

But the digital channel is also reshaping the physical store, starting with location. L.L.Bean, for example, is mining data from its online and catalog operations to find the best spots to put its new stores.

“We’re looking for two types of markets,” Kacere says. “We want to find ones where we have a high penetration of customers already, and we can provide them with more services and products.” At the other end of the spectrum, the retailer is looking for very low-penetration markets—“where L.L.Bean isn’t that well known, where we can bring them the brand in 3-D, and attract a new generation of customers,” he says.

L.L.Bean’s stock format for its stores has evolved dramatically since the company opened its first store outside of Maine, a 75,000-square-foot (7,000 sq m) location in McLean, Virginia, in 2000. Consumer research helped the company figure out that it could provide customers with “a really good representation of the L.L.Bean product” in about 20 percent of that space and still tell the story of the brand effectively through design features, Kacere says.

“We’re big on tradition” he says. “We’re really focused on making our store experience feel authentic and genuine.”

The company has developed specific ideas about where it wants to be within a shopping development. It typically locates in lifestyle centers where its stores can be surrounded by dining and entertainment venues and by other premium retailers, Kacere says. It is crucial to have an outside-facing or exterior storefront where the company can deploy its logo and green tower exterior, as well as the trademark facade built from reclaimed materials. “Typically, you won’t find us buried deep in a mall,” he says. “We need high visibility and also direct access to parking.”

That sort of visual presence is particularly important for online retailers who are trying to leverage a physical location for brand building. “You want to be able to get into the mood, the atmospherics from 50 feet away,” explains Matthew Hopkins, director of architecture and sustainability for Streetsense, a Bethesda, Maryland–based firm that provides interior and exterior design as well as marketing consulting to retailers. “You need to utilize the storefront for storytelling so that you stand out. You have to be able to draw them out of their cars.”

Less Space, More Design

But it is the interior of clicks-to-bricks stores that provides the most striking contrast to the past—and the most telling glimpse of the new mode of retailing. In the old-school footprint for a 2,000-square-foot (190 sq m) soft-goods store, Hopkins says, about half the space typically was allotted to what he calls “dirty space”—backroom inventory storage, office and record-keeping space, and other parts of the store that customers never glimpsed. The remainder might be filled with shelves or racks densely stocked with products so that customers could find and pick up what they wanted without assistance.

In contrast, the new stores function more as “web rooms” where customers can see and handle products and have their questions answered. They then can order merchandise that will be delivered to them or held for in-store pickup. That means the backroom space can be shaved to 20 to 25 percent of the total leased. Even if the store itself is significantly smaller, the public space is roomier and less cluttered.

The trend is to augment less-dense displays with higher-quality furnishings, such as couches, a demonstration kitchen for cooking equipment, or—in the case of an audio store—artfully designed listening booths or a performance space, Hopkins says. It is all designed to keep customers in the store longer and to get them to interact with the products—and the staff—even as the customers use electronic devices to actually order their purchases, he says.

This approach has an added cost: spending on interior design can climb to $200 to $300 per square foot ($2,200 to $3,200 per sq m), an expense comparable with that of a high-end hotel lobby, Hopkins says. But the investment may pay off if it engages customers and gives them an experience that encourages them to spend. “You have to give them a reason to come to the store instead of just jumping on Amazon,” he says.

The big question for the future is how real estate developers, architects, and property managers can best facilitate the clicks-to-bricks trend. Tron predicts that flexibility and the ability to accommodate a variety of store footprints will be important.

Developers will have a better chance to attract retailers such as L.L.Bean if they try to get away from formula and if they concentrate on creating distinctively different environments for retail, Kacere says.

“I think it’s really about developing projects that aren’t cookie-cutter—mixed use that provides more visual variety, unique stores as tenants, and unique designs for storefronts,” he says. “You want to create some interesting perspectives for customers, but also give them what they need for an easy, fast shopping experience.”

PATRICK J. KIGER is a Washington, D.C.–area journalist, blogger, and author.