Redeveloping more than 20 acres (8 ha) of intensely developed land at the urban heart of Salt Lake City into an integrated, large-scale mixed-use complex during the worst of the Great Recession was a complicated and expensive proposition. Building seven office towers, almost 1 million square feet (93,000 sq m) of retail space, more than 800 units of urban for-sale and rental housing, more than 5,000 underground parking spaces, and a two-level, 70,000-square-foot (6,500 sq m) grocery, plus redeveloping a 342-room hotel, might be expected to require high levels of mathematical dexterity.

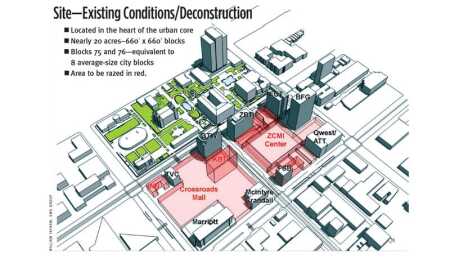

But the partners for City Creek Center—the Taubman Centers retail development entity and City Creek Reserve Inc. (CCRI), the development arm of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, or Mormon Church—metaphorically used simple arithmetic to accomplish this feat between announcement of the project in 2006 and its completion in March 2012. They subtracted two aging and poorly performing shopping centers, ZCMI and Crossroads Mall; subtracted (through implosion) the high-rise Key Bank; then added back some green space, uncovering a natural creek, as well as the mixed uses.

The partners then divided two of Salt Lake City’s ten-acre (4 ha) blocks into four quadrants each, creating eight development blocks 330 feet (100 m) square—large by urban standards but far more pedestrian friendly than the original configuration—resulting in multiple new development options.

Those moves opened up possibilities to add many new buildings and uses, including a two-story, 124,000-square-foot (11,500 sq m) Nordstrom department store, and on Main Street, a three-level, 150,000-square-foot (14,000 sq m) Macy’s behind the reconstructed facade of the historic ZCMI department store.

Also added to the development are the new 26-story Key Bank building, as well as the 22-story Eagle Gate Tower (with a food court at its base), now known as the World Trade Center Utah, consolidating at one site the previously scattered government and nonprofit economic development agencies and private sector international service providers. The new Harmon’s upscale grocery on an adjacent block extends the reach of City Creek Center, and five additional new office towers, including the 19-story Gateway Tower West, 14-story First Security Building, 18-story Zion’s Bank Tower, and eight-story Deseret Book Building —add to the scale of City Creek Center and boost its weekday working population, providing support for the retail tenants.

These moves led to another—a multiplication of the connections among all the uses along new urban, pedestrian-oriented streets that line the natural creek uncovered and rebuilt as part of the project, as well as along the pedestrian ways that lead to it.

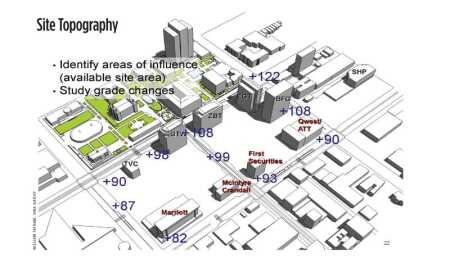

Those connections are not simply horizontal but also vertical because the site slopes 40 feet (12 m) from its northeastern to southwestern corners, notes René Bihan, chief landscape architect of City Creek Center and managing principal of San Francisco–based SWA Group. Such topographic barriers might have precluded connections across the site, but the developers chose to view them as an opportunity to create active urban spaces at multiple levels that draw pedestrians into the project from many locations. As noted by CCRI architect Bill Williams, who coordinated the work of multiple architects and engineers charged with different pieces of the project, “There are no back doors to City Creek Center.”

For retailers, this use of multiple levels and entries can be helpful in evening out foot traffic, which declines at upper levels of retail projects. It is well established by retail developers that shoppers go down much more readily than they go up. At City Creek Center, people arriving by car, from the surrounding streets, and from office buildings and the hotel enter the project on different levels.

However, dividing pedestrian and traffic flows in this manner has its downside. The developers managed this by placing retail space primarily on the two main levels so shoppers would walk by most of the stores. As Taubman executive architect Ron Loch explains, shoppers typically walk a figure-eight pattern through a two-level center, walking along both sides of one level, counterclockwise in the United States, then moving to the next level and walking both sides back to their starting point. Returning to one’s starting point is considerably harder in centers with more than two levels.

In addition, the ability of a shopper to get from one side of the mall to the other is highly desirable for retailers. Usually, such shopping is only difficult on the second level of retail centers, where bridges are required to span the open interior. But at City Creek Center, the creek divides the lower level as well, so bridges every 60 feet (20 m), or about every two stores, were required. The width of the pedestrian street had to be narrowed to about 35 feet (10.7 m) in order to not discourage that cross-mall shopping.

The creek also presented unique opportunities for creating dramatic connection spaces, including those flanking two waterfalls more than 18 feet (5.5 m) high that course through the descending grades. Bihan calls these pathway connection points “urban knuckles” that provide plazas and terraces with pleasing vistas that create special attractions for pedestrians lured to the project by cafés, restaurants, and shops. Unlike walkways in enclosed retail centers, at City Creek Center these pathways are open to the sky. But in an accommodation to Salt Lake City winters, the retail-lined creek has a retractable glass roof that turns the pathways into a winter garden.

Because Main Street, which bisects the project, is open to vehicles and contains the TRAX light-rail line—which has a station in front of Macy’s and provides free transit through downtown—the two main project blocks along that street are connected by a sky bridge. Rather than just provide a simple connecting structure, the architects—at the urging of the American Institute of Architects, which held a charrette on the issue—designed the sky bridge to resemble the major bridge built to arch over the creek. They also hired an artist to etch shadow patterns in the sky bridge glass similar to those cast by tree leaves on a creek, helping make the structure a metaphor for the creek and open up vistas of the Mormon Tabernacle and Temple Square to the north and downtown to the south.

The addition and multiplication of so many pedestrian intersections, levels, and uses at those urban knuckles activates spaces within the enormous Salt Lake City blocks. The Mormon Church, through CCRI, believed that housing would play a critical role in revitalization of downtown adjacent to the heart of the church’s operations. The church had to think long term about the potential return on housing because the economics of housing development, especially during and after the Great Recession, have been particularly challenging.

CCRI took considerable risk in developing both rental and for-sale housing on the scale that it did, providing more than 800 units, 425 of which are for-sale condominiums in three towers.

As Loch and Williams point out, once a 5,000-space underground parking facility is built at a cost of nearly $50,000 per space for a vertically integrated mixed-use complex, it is very expensive to come back later to design and build new structures above it, to say nothing of carrying the cost of the parking structure in the meantime. The issue was particularly acute because the developers determined to supply parking at 4.5 spaces per 1,000 square feet of retail space, though some parking is shared on weekdays, dropping the level to an effective 2.5 spaces per 1,000 square feet.

The 20-story Key Bank office tower was imploded, and replaced by the new 26-story Key Bank building, which sits in an active, multilevel pedestrian plaza, providing customers for the restaurants and cafés during the week. The project’s below-grade parking structure was built on a large 30-by-60-foot (19.1 by 18.3 m) bay size not only to provide easily accessible parking with few columns, but also to permit the most flexibility in what was developed above. (William Tatham, SWA Group)

The parking structure, which has up to four levels, was built with a large 30-by-60-foot (9.1 by 18.3 m) bay not only to provide accessible parking below grade with few columns, but also to permit the most flexibility for the uses that would be developed above; different uses require different modular bay sizes. The financial imperative to service the debt required to build the parking structure also impelled earlier development by CCRI of the apartments and condos. Fortunately, Salt Lake City’s extraordinarily wide, 132-foot (40 m) rights-of-way mean access to the underground parking could be easily accomplished in many locations.

To design the housing, CCRI selected Portland-based architecture firm Zimmer Gunsul Frasca (ZGF). The four housing projects at City Creek Living are the Regent, a 20-story, 149-unit condo tower on the southern portion of the eastern block; 99 West, a 30-story, 185-unit condo tower on the northwestern corner of the western block; Richards Court, a ten-story, 90-unit rental apartment building above retail space across from Temple Square; and City Creek Landing, a seven-story rental building with 111 units above retail space. At City Creek Landing, units range in size from 555 to 1,242 square feet (52 to 115 sq m) at monthly rents ranging from $904 to $1,958. Local real estate brokers say the apartments are nearly fully leased; the church and CCRI do not release financial information.

Another characteristic of City Creek Center more unusual in the West than elsewhere in the United States is that the Mormon Church, through its nonprofit entity CCRI, retained ownership of the land under not only the office buildings and rental apartments, which it owns outright, but also under the mall, grocery, and condo buildings, which it does not own. Ground-lease income provides a long-term, though initially modest, return.

That long-term perspective on maintaining the vitality of the area near the Mormon Church’s historic base was critical to the church’s interest in undertaking the considerable risks of developing a large-scale mixed-use project in a challenging environment.

Though the fact the condominiums sit on ground-leased land could make them initially more difficult to sell, prospective buyers could view the set-up as beneficial. Rather than owning (along with the other unit owners) an interest in the land on which the towers sit, each condo-unit owner has the backing of the entity that owns the land—in this case an owner that is financially solid with long-term historic, cultural, and economic roots in the area and an interest in ensuring the continued maintenance and vitality of its investments and the urban environment.

“It was the church that gave birth to the city,” Williams notes, “and it could not let the flagging ZCMI Center, which it owned, and the Crossroads Mall, which it then acquired, be a bad neighbor either to the Mormon Tabernacle or the downtown.”

Taubman’s development agreement with CCRI is a complicated one to characterize, but in essence CCRI still owns the land. Though it is a nonprofit entity, CCRI pays property taxes on its holdings. Management of a mixed-use complex can be difficult, but CCRI decided that Taubman should manage all the common areas, including those that go through retail corridors in residential areas, though there are cross easements with the respective entities.

Although an arithmetic metaphor for a complicated project oversimplifies an enormous undertaking, it does highlight that a long-term development perspective in which to realize returns—embarked upon by an international institution that is committed to revitalizing the city to which it gave birth (and from which it continues to run diverse interests)—may require such simplification and resolve in order to ensure that the components integrate well with one another and with the downtown that surrounds it.

William P. Macht is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University in Oregon and a development consultant. (Comments about projects profiled in this column, as well as proposals for future profiles, should be directed to the author at [email protected].)