Editor’s note: “Rethinking PADs” in the January/February 2015 issue on pages 87–91 describes the market and regulatory trends based on demographic, economic, and cultural changes that have created a broader market for PADs, and the strategies being adopted to meet them. This article outlines the economic, financial, design, and construction solutions that both larger and smaller developers have crafted to supply units to serve the growing PAD market.

Because of regulatory diversity and complexity across jurisdictions, the design and construction adaptations required, and the singular nature of demand, few developers have ventured into development of private accessory dwellings, or PADs. But that is beginning to change. The first wave of change is coming from architects, contractors, and small builders who act as consultants to homeowners seeking to add a PAD to their homes. For example, New Avenue Homes, based in Emeryville, California, acts as a fee-based developer for clients in the San Francisco Bay area. The company retains architects and contractors, prepares budgets and schedules, obtains approvals, and supervises construction. Projects are one-off deals with average prices ranging from $200,000 to more than $400,000. Unlike homebuilders’ typical practice, all design work on these PADs is billed hourly, although construction work is based on competitive bids.

Company owner Kevin Casey represents a different profile of PAD developer entering the field and devising new solutions to develop PADs. Before beginning a career in finance, Casey worked in Indonesia as a Fulbright Scholar on economic and community development and then obtained a master’s degree in business administration from the University of California, Berkeley. He conceived a plan to develop PADs for owners on a turnkey basis, including arranging financing for the units using two-thirds of the rental income from them to pay the development debt service. While the Great Recession and lenders’ limited experience with the rental income streams of PADs have held back this business model, Casey continues to follow his fee-based development model.

One of New Avenue’s projects is a 1,478-square-foot (137 sq m), two-story, two-bedroom, two-bathroom house—a rebuild of a dilapidated cottage in Berkeley. The owner of the adjoining home built it for investment in an area in which comparable rents range from $3,200 to $4,500 per month, says Casey. He contends that his market of buyers values PADs equally to their primary houses.

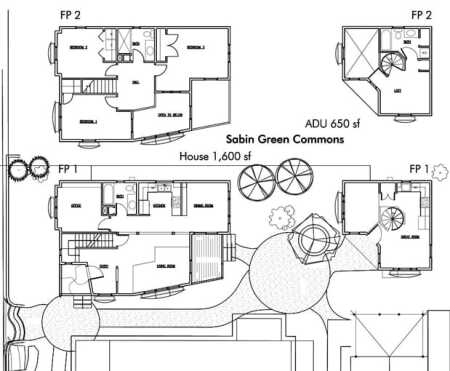

Because condominiums are governed by state statute, Portland developer Eli Spevak was able to create and sell four detached homes (two primary dwellings and two detached PADs around a shared, central, circular brick-paved courtyard) as condominiums. Two first-time homebuyers, otherwise excluded by market prices from buying larger houses, could therefore purchase the two small units. (Lakeman Communitecture-Spevak)

Speculative Developers

Some entrepreneurial developers have devised new ways to create more affordable housing without the complications of using public subsidies. Eli Spevak, owner of Portland, Oregon, development company Orange Splot, says, “I had learned about ADUs [accessory dwelling units, another term for PADs] as a planning student and was intrigued by the possibility of using the condominium legal structure as a way to separate ownership between ADUs and primary residences.” He found and bought a 75-foot-wide-by-100-foot-deep (23 by 30 m) property with a large side yard, a 1,100-square-foot (102 sq m) house, plus a detached two-car garage. Platted as two 37.5-foot-wide (11.4 m) lots, R-5 zone requirements precluded four house lots and houses.

But Spevak was able to comply with local zoning requirements by using the condominium structure for ownership, because condos are governed by state statutes. He created and sold four detached homes (two primary dwellings and two detached PADs) as condominiums. “Zoning and building codes determine how properties can be partitioned into lots, what can be built, and how land and buildings can be used,” Spevak notes. “But with few exceptions, these regulations are typically ‘tenure neutral,’ meaning that they have nothing to say about the relationship between who lives in a home and who owns it,” he says.

In the project he called Sabin Green, each home has its own porch facing onto a shared, central, circular brick-paved courtyard.

The smallest house, measuring 530 square feet (49 sq m), sold for $143,000; the 576-square-foot (54 sq m) garage conversion sold for $113,975; the rehabbed 1,152-square-foot (107 sq m) bungalow sold for $275,000; and the largest—a 1,616-square-foot (150 sq m) house—sold for $362,700, netting an average sales price of $231 per square foot ($2,418 per sq m). Two first-time homebuyers, who were priced out of buying larger houses, could purchase the two small units. In states that, unlike Oregon, have laws enabling cooperatives, it might be possible to structure independent financing of such homes through a single cooperative mortgage, or individual share loans, with each owner’s corporate shares entitled to a proprietary lease on respective units.

Following Spevak’s model, Portland developer Kristy Lakin bought a 20,000-square-foot (1,858 sq m) lot in southeast Portland, demolished the existing house, and subdivided the lot into three parcels, two that measure 7,000 square feet (650 sq m) and the third at 6,000 square feet (557 sq m). She is building three houses, each with a PAD, for a total of six residences, and superimposing a condominium legal structure over what she calls Woodstock Gardens. The first 650-square-foot (60 sq m), one-bedroom, one-bathroom PAD sold for $195,000 in two days on the market in 2014. The other units are expected to be completed this spring.

Financing

Financing has been a substantial impediment to more widespread development of PADs. Most people need to use their own savings and home equity lines of credit to pay for development. Some are able to refinance upon completion of the development and demonstration of a new income stream. But lenders have been slow to determine how to value PADs. Few comparable sales are available with which to compare proposed units, and the lack of standardization makes limited sales comparisons difficult.

Residential lenders are not accustomed to using a commercial income capitalization method for residential properties, although some lenders will consider income from PADs after two years of documented rental income. Determination of net operating income (NOI) can be more difficult since operating expenses for property tax allocations, separate utilities, repairs, maintenance, and management are not consistent. And, since most residential lenders who originate loans plan for quick loan resales in secondary markets, these atypical mortgages are problematic. Terminology used by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) also complicates financing and mortgage resales. Secondary-mortgage guidelines from Fannie Mae discourage accessory units, noting that Fannie Mae will purchase loans on properties with legal accessory units only “if the value of the legal second unit is relatively insignificant in relation to the total value of the property.”

To eliminate the NOI computation, Taylor Watkins, a Portland appraiser, developed and published, with Martin Brown, in the fall 2012 issue of Appraisal Journal, an income capitalization method for jurisdictions in which both primary and accessory dwellings can be rented. They use a gross rent multiplier (GRM) model for both units, then apply a land discount formula to adjust for the fact that the two units share the same piece of land. The results of their initial studies indicate that PADs account for one-quarter to one-half of the combined property value. But this model is not yet widely accepted, and the database is still embryonic. Some local credit unions, which are more likely than banks to hold loans in their own portfolios, are experimenting with shorter-term rehabilitation mortgages for PADs in areas like Portland where more units have been permitted and constructed since the city waived its system development charges in early 2010. The Wall Street Journal reports a proprietary Zillow analysis claiming that homes with legal PADs were priced as much as 60 percent higher than houses without them.

Where PADs are freestanding and part of site condominiums, some borrowers have been able to take advantage of an FHA exclusion from HUD approval. Site condominiums are those encumbered by a condominium declaration in which each PAD is detached; the structure contains no common or limited common area; PAD owners pay insurance and maintenance costs; and common assessments are collected only for areas outside the unit’s footprint.

With a large downpayment, the first buyer at Portland’s Woodstock Gardens site condominiums had no problem obtaining a mortgage on the $195,000 purchase of a freestanding 650-square-foot (60 sq m) PAD.

Community Developers

Larger community developers and national builders are beginning to take a different approach to appeal to changing demographics and a growing market for PADs. One of the largest, Cleveland-based Forest City Enterprises, is developing the Stapleton new urbanist community on 4,700 acres (1,900 ha) of the former Denver airport, planned to include 3,500 single-family houses, 480 apartments, and 2 million square feet (186,000 sq m) of retail space. Heidi Majerik, Stapleton’s development director, says, “We wrote ADUs into our design book to encourage them and initially had four builders that offered them as an option.” She notes that more than 100 buyers selected that option before the independent Denver Water utility imposed a second system development fee of more than $10,000 on each ADU, an action that heavily affected further PAD development.

However, Stapleton’s experience is instructive because the only options offered by the builders were carriage-unit PADs built above garages, which could have been built as bonus rooms; builders could easily adapt plans to either use. For buyers, prices were substantially lower than individual PAD conversions, adding about $40,000 to $60,000 to home prices to gain 600-square-foot (56 sq m) PADs. Because permitting approvals and construction were done in conjunction with homebuilding, development costs could be reduced. Even more important, PAD options were financed along with the houses themselves in a single mortgage, avoiding the financing difficulties noted earlier.

In 2012, Miami-based homebuilder Lennar, recognizing the national appeal of flexible PADs, introduced first-floor PADs at the entries to some of its houses that it brands NextGen-(Home within a Home) homes. Lennar now offers them in Stapleton as well as about a dozen other states, primarily in the West and South. Advertised as multigenerational units, these approximately 500-square-foot (46 sq m) PADs have a great room with a kitchenette, dining and living spaces, a covered patio, a private bedroom, a walk-in closet, and a bathroom. Some of the PADs can be entered directly from the exterior at the front porch and internally from the entry foyer. Such houses have shared power, gas, and water meters for the primary house and the PAD, and the PAD kitchens contain only a microwave oven, which may skirt formal PAD status, which calls for autonomous units. By the end of 2013, Lennar had sold about 1,200 of these units in more than 100 communities and claims a 27 percent growth in sales of such homes year-over-year. Such PADs are flexible because they can also be used as home offices or guest suites.

Besides being financed in a single mortgage, PADs can offer substantial financial benefits for homebuyers. Parents might wish to make the downpayment as a gift to their adult children, while saving themselves about $1,200 to $1,500 monthly in alternative rental expenses while the adult children PAD/homeowners service the debt and build equity. If the parents later need assistance from their children, the housing arrangement might become a substitute for assisted living. In that case, the savings could amount to $4,000 to $6,000 per month, or about $500,000 to $700,000 over a ten-year period, roughly equal to the full cost of the house and PAD.

PulteGroup, one of the largest homebuilders in the United States, does not offer a permitted PAD per se, but several floor plans have the flexibility to accommodate a multigenerational household with a first-floor bedroom/bathroom suite in lieu of a den; a bedroom and bathroom carved out of a third garage bay, or a what it calls a grand retreat over the garage that includes a bedroom, bathroom, kitchenette, and living room. Builders Ryland and KB Home offer similar alternatives. Toll Brothers offers a second master suite on the first floor with an option for a morning kitchen, which includes a sink, an under-counter refrigerator, and storage cabinets.

Prefabrication

MED-Cottages measure 24.6 by 11.6 feet (7.5 by 3.5 m), narrow enough to fall within common 15-foot (4.6 m) wide-load transport limits. They are constructed on a steel base with light-gauge steel studs and roof framing, which keeps them square and sturdier for multiple transports. (N2Care MedCottage)

One might expect that the smaller size, simpler design, and the potential for easier transportation of freestanding PADs might yield economies of scale that would make them a natural fit for prefabrication. But so far, few companies have experimented with prefabricated PADs.

The largest national residential prefabricator, Waltham, Massachusetts–based BluHomes, with a 250,000-square-foot (23,000 sq m) factory in Vallejo, California, has built relatively few in connection with the construction of a main house. For example, a rectangular 480-square-foot (45 sq m) PAD studio with a kitchenette, a bathroom, and combined living, dining, and sleeping space has 12-foot (4 m) ceilings and sliding glass doors that open onto a private deck at its Breezehouse model in Healdsburg, California.

A modern, rectilinear 475-square-foot (44 sq m) Origin model PAD at Joshua Tree, California, like the Breezehouse and Glidehouse model units, costs about $250,000 exclusive of land, site work, and soft costs, including design, permitting, systems development charges, finance fees, and so on. BluHomes acquired the assets of Modern Cabana, a builder of smaller units ranging from about 120 to 300 square feet (11 to 28 sq m), but it has not yet made any announcements about the sale of PADs or pricing.

Although PADs can be factory built in less than two weeks, orders still come in on a singular basis, and the PADs need to be transported to dispersed sites, are permitted under disparate local rules, and require the hiring of local contractors who are supervised by BluHomes. As a result, unit prices can exceed $500 per square foot ($5,400 per sq m), and the economies of prefabrication have not yet been realized. However, proponents foresee increased volume—and the possibility of economies of scale—if PAD regulation is liberalized, increasing market demand.

The experience of Lanefab, a design-build company in Vancouver, British Columbia, run by people with backgrounds in architecture, engineering, and carpentry, may suggest how growth could occur on a local basis following Vancouver’s liberalization of PAD regulation. Lanefab uses structural insulated panels (SIPs) that are cut to specific sizes and shapes for each custom design. Says owner Bryn Davidson, “Our niche is higher-end projects with owner-occupiers or their family.” The panels are preassembled at the factory and then installed on site. Using SIPs, Lanefab’s typical house can be framed, insulated, and ready for roofing in two to five days with a total building time of six months. “While more expensive materials for prefabrication do not save money, with labor savings using more expensive SIPs over stick-framing, the cost is about equal, but energy savings are superior,” Davidson says.

By focusing on designing and building laneway houses using partial prefabrication in a jurisdiction with liberalized rules and growing market demand, Lanefab has been able to complete dozens of PAD projects since 2009. For example, its first solar laneway house, built as a separate PAD adjacent to the primary house on an existing 50-by-125-foot (15 by 38 m) residential lot, measures 1,050 square feet (98 sq m), with one bedroom and two bathrooms constructed for the owners of the existing main house. With SIPs, light-emitting diode (LED) lighting, a 500-gallon (1,893 liter) in-ground rainwater tank, graywater and ventilation heat recovery systems, an air-source heat pump, and 12 solar roof panels, the solar laneway house achieves net-zero-energy status, at a construction cost of about $360,000. “Because of the discount relative to the cost of a similarly sized condo, we have a niche market of owners putting features into their small units, including solar arrays, high-end appliances, steam showers, Jacuzzis, etc.,” Davidson says.

But in Vancouver, $360,000 is still less expensive than a condominium unit of a similar size, Davidson notes. “If a homeowner has owned a piece of land for five to ten years, then she or he can have over $1 million in equity tied up in the value of the property,” he says. Home equity loans on that value are readily available. Downsizers who then rent out both the main house and basement suite would see the highest return on investment (ROI) and have considerable flexibility in their retirement years. Each unit could rent in the $1,700- to $2,400-per-month range, Davidson says.

One of New Avenue’s projects is a 460-square-foot (43 sq m) modular demonstration house built in Palo Alto, California, with support from the U.S. Department of Energy and the cities of San Jose and Palo Alto. Developer Casey says, “As a modular home, it was built under factory conditions, was inspected and permitted by the state of California, and can be installed on any property in the state.” He says it is for sale at $160,000.

In Oakland, Larson Shores Architects formed a division called Inspired Independence that uses a panelized process to build 465- to 538-square-foot (43 to 50 sq m) PADs for about $200,000. They use lightweight R-25 SIP foam panels, which they say can be walked into the job site, navigating around the constraints posed by narrow side yards, power lines, or other obstacles, more easily than fully prefabricated units.

For $160,000, New Avenue Homes prefabricated a 460-square-foot (43 sq m) modular demonstration house in Palo Alto supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, as well as the cities of San Jose and Palo Alto, and inspected and permitted by the state of California that can be installed on any property in the state. (New Avenue Homes)

Assisted-Living Alternative

N2Care, based in Blacksburg, Virginia, prefabricates MED-Cottage, its branded name for transportable PADs for assisted living that are equipped with medical devices usually provided only in institutional settings. The rising cost of long-term care insurance and the provision of costly, labor-intensive services, along with often-inadequate retirement resources with which to pay for them, have prompted an increasing number of adult children to move their parents into their single-family detached homes. But such houses usually are not barrier-free and are expensive to retrofit.

In response to these situations, Wesleyan minister Kenneth Dupin founded N2Care, working with the nearby Virginia Tech University’s College of Engineering to design 288-square-foot (27 sq m) prefabricated MED-Cottages with a handicapped-accessible bathroom, a kitchenette with an accessible under-counter refrigerator and a microwave oven, a combination washer-dryer, and rubber floors. Each cottage has a mobile lift with preinstalled tracks to help move residents from bedroom to bathroom. “One of the primary reasons people have to go to nursing homes is that caregivers can’t lift them anymore,” Dupin notes.

Many high-tech instruments are installed in MED-Cottages. A runway mat stretches from the bed to the toilet and lights up when walked on. Web cameras hooked to computers in the main house enable caregivers to monitor the occupant’s movements. Other systems can track blood pressure, glucose levels, heart rate, and blood oxygen and carbon dioxide levels and can alert family and physicians to health crises. If, for example, the resident fails to take medication from a dispenser on time, the system audibly reminds the patient and sends a text message to caregivers.

MED-Cottages are connected to the main house’s water, sewer, and power lines. The state of Virginia passed a statute in 2010, followed by North Carolina, that permits medical dwellings on a resident’s property provided that a physician verifies that the patient needs assistance with at least two daily functions, such as bathing, dressing, and eating, and provided further that the units are removed when the patient no longer needs them. Purchase of the cottage starts at about $85,000, but N2Care will facilitate repurchase for about $38,000 after two years of use. “If you compare it to nursing home costs, which can run at least $6,000 to $8,000 per month in Virginia, and higher in many other states, that’s cheap,” says Dupin. But, of course, the caregiving is not included. N2Care may seek a capital partner to facilitate a leasing strategy for a growing market.

MED-Cottages measure 24.6 by 11.6 feet (7.5 by 3.5 m), narrow enough to fall within common 15-foot (4.6 m) wide-load transportation limits. The units are constructed on a steel base with light-gauge steel studs and roof framing, which keeps them square and sturdier for multiple transports. A center roof section is raised with multiple narrow clerestory windows on both sides admitting light into the center of the unit while raising exposed gable ceiling heights of the small unit. Double entry doors facilitate the ingress and egress of medical equipment. Barrier-free bathrooms contain roll-in showers and multiple grab bars.

However, several problems are inherent in PAD prefabrication. The essence of the economies generated by prefabrication is the scale of production using mass assembly of standardized products. Differing regulations restrict developers’ ability to develop PADs of standardized sizes and designs for disparate locations. PADs are often precluded in single-family-detached zones, and even those that permit or encourage them have widely diverse local zoning and building regulations. Portland, for example, which encourages PADs with systems development charges (SDCs) waivers, precludes them within 60 feet (18 m) of front property lines, and limits the entry placement, height, roof pitch, exterior finish materials, trim, and window proportions. Even if regulations are harmonized, prefabricated PADs are more costly on an area basis because of their smaller sizes, added transportation, and on-site crane needs. Furthermore, the physical constraints of shape, access, trees, and utility lines vary widely according to the site, so custom design is often required.

Perhaps more promising methods will depend upon partial prefabricated systems such as the kind of SIP panel wall, floor, and roof components that Lanefab uses, along with plumbing and mechanical core walls and prefabricated bathroom and kitchen components that some European manufacturers have pioneered.

Larger-scale PAD development by community builders, with community-wide PAD rules buildable with unified construction and finance, may lead to less expensive, more prevalent PAD development. However, new homebuilding on large-scale tracts supplies a smaller market.

The opportunity for retrofitting single-family detached areas of cities and suburbs is larger, in terms of market demand and available land. Interest is growing: a Portland tour of built PADs in June 2014 sold 850 tickets—500 more than expected.

Another route to more infilling of cities and suburbs with PADs could depend upon the formulation of a model uniform PAD-enabling statute that can be adopted by all states as part of the American Law Institute (ALI) Model Land Development Code, similar to the Uniform Condominium Code. State legislation enabling cooperatives might also be modified to authorize PADs on a more uniform basis. Unless statewide statutes are broadly permissive, local ordinances may restrict actual construction of PADs either through exclusionary intent or the inadvertent inhibitions created by well-meaning—but cumulative—restrictions on parking, occupancy, location, and design standards.

The ultimate answer may lie in the broader elimination of single-use zoning, exacerbated by single-housing-type restrictions, still less than a century old, which has divided cities and suburbs by age, income, and socioeconomic class. Without them, a wide variety of developers could more easily enrich the intergenerational fabric of both urban and suburban life.

William P. Macht is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University (PSU) in Oregon and a development consultant. Naomi Cole, a graduate of the PSU Center for Real Estate, undertook extensive research for this article. She works in green building and energy efficiency and is a developer, an owner, and an occupant of a house with a PAD. Her unit, and other Portland case studies, are featured at www.accessorydwellings.org. (Comments about projects profiled in this column, as well as proposals for future profiles, should be directed to the author at [email protected].)

![Western Plaza Improvements [1].jpg](https://cdn-ul.uli.org/dims4/default/15205ec/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1919x1078+0+0/resize/500x281!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fk2-prod-uli.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Fbrightspot%2Fb4%2Ffa%2F5da7da1e442091ea01b5d8724354%2Fwestern-plaza-improvements-1.jpg)