A redevelopment of a 1980s strip center in a suburban town programs urban-style mixed uses with 1,500 fewer parking spaces than would have been required without sharing.

Demand for more affordable class A and creative office space served by a mixture of uses in a more urban setting has led to a newer form of mixed-use development in suburban towns. Referred to as “surban,” these developments meld the amenities of urban places with the convenience of smaller, less-congested, and more walkable suburban environments.

Both urban and suburban developers still usually build single-use buildings. Urban developers typically build single-use office, apartment, or hotel buildings, some with a modicum of retail space at their bases, supported by underground parking for the users of that building. Suburban developers typically build single-use retail, office, apartment, or hotel buildings surrounded by parking lots. Major reasons for this dichotomy are that available downtown sites are rarely large enough for truly mixed-use projects, and that large suburban sites are often not zoned for mixed uses.

In recent years, however, developers have seized the opportunity to create larger-scaled, functionally integrated, mixed-use surban developments to replace outmoded closer-in strip centers. These new developments truly meet ULI’s three-part definition of mixed use: they have three or more revenue-generating uses; they are physically and functionally integrated; and they are developed according to coherent, design, construction, economic, market, and management plans.

Knowledge Finder: Parking Policy Innovations in the United States

Member Opportunity: U.S. Parking Policy Innovation Contributor

Surban Development Opportunities

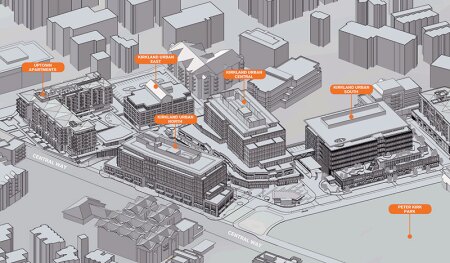

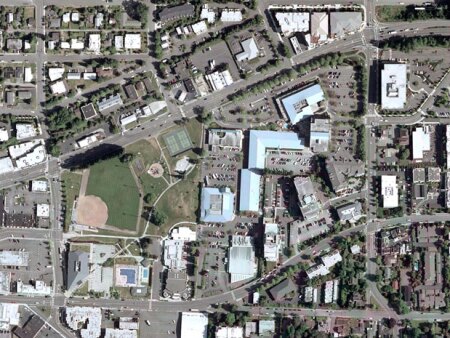

Bellevue, Washington–based Talon Private Capital found just such an opportunity at Parkplace Center, an 11.5-acre (4.7 ha) strip center in nearby Kirkland, built in 1980 and anchored by a 25,000-square-foot (2,000 sq m) QFC grocery. The site at Central Way and Sixth Street overlooked the 7.5-acre (3 ha) Peter Kirk Park, with Seattle across Lake Washington in the distance, and was just 1,500 feet (460 m) away from City Hall in the original town center. The town had been founded in 1888 by Peter Kirk, a British-born businessman who had formed Kirkland Land and Development Company, which bought thousands of acres of land for the new town he envisioned as the “Pittsburgh of the West.”

The real estate arm of Prudential Insurance, Prudential Global Investment Management (PGIM Real Estate), and Seattle developer Touchstone Corp. bought Parkplace Center in 2007 for $59 million with the intent to develop a 1.8 million-square-foot (167,000 sq m) mixed-use project incorporating 1.2 million square feet (111,000 sq m) of office space in five buildings, a 175-room hotel, a luxury sports club, and 300,000 square feet (28,000 sq m) of retail space, including a grocery store. The overall development required about 5,000 parking spaces. However, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, the economics of that program appeared problematic, and a new approach was needed.

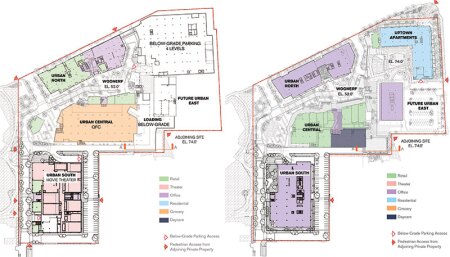

In 2013, PGIM brought in a local partner, Talon Private Capital, to reenvision the project, renamed Kirkland Urban in fall 2015. Talon proposed what it considered a more feasible phased development program consisting of 650,000 net rentable square feet (60,000 sq m) of office space; 165,000 square feet (15,000 sq m) of retail space (including a more upscale 50,000-square-foot (4,600 sq m) QFC grocery, doubling its size; a 54,000-square-foot (5,000 sq m), nine-screen cineplex; and 300 apartments—for a total of 1.1 million square feet (102,000 sq m) served by 2,000 underground parking spaces. That mix produced an average shared parking ratio of only about 1.5 spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 sq m), far below conventional suburban ratios but higher than typical downtown ratios.

Functional Integration

That development program’s mix of uses could produce synergies that functionally integrate those uses.

For example, the apartment units would be particularly desirable to employees of tech-oriented office tenants, who would rely on the services of the on-site retail/grocery/restaurant and theater components, which could in turn generate premium rents for all uses while decreasing demand for additional parking. The cinemas could take advantage of the mostly vacant office parking in the evening as well as stimulate restaurant businesses in the more profitable evening hours. And the availability of a large pool of shared parking could increase the efficiency of each expensive underground parking space while lowering the total parking count, which would reduce development costs, thereby helping make the whole mixed-use project more feasible.

Physical Integration

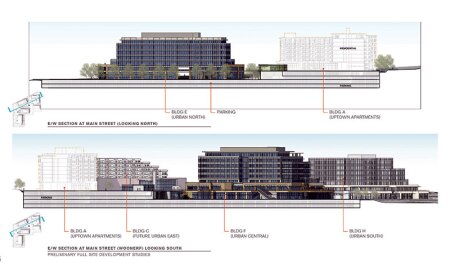

Talon’s smaller development program also would take maximum advantage of the slope of the site, which descends more than 35 feet (11 m) from east to west. Seattle-based architecture firm CollinsWoerman used the slope to tuck four levels of parking under eastern sections of the project, as well as two continuous levels under the whole site. That increased the space efficiency of the parking floor plates, resulting in less space wasted on circulation ramps. Even more important, those larger floor plates make the shared parking pool more efficient because users of different components can find and occupy vacant spaces in the larger contiguous shared parking pool more quickly.

Building the parking floor plates on such a significant slope also meant that the need for expensive excavation would be reduced. Still, depending on which expenses are included, the parking cost ranged from $35,000 to $45,000 per space, says William Leedom, managing director at Talon.

CollinsWoerman was also able to take advantage of the slope to make the site more urban. Large grocery stores have mostly blank walls because refrigerated fixtures, walk-in cooler supply rooms, ovens, and service facilities need to be placed on the perimeter. Architects buried the bulk of the grocery store, the loading docks, and most of the perimeter walls in the slope. Unlike the practice of most suburban grocers, all loading for QFC is done below grade. Cinemas also have long stretches of blank walls, and the architects were able to bury them into the slope as well. Yet both the grocery and the cineplex have entrances that open onto the lower park level, which yields views across Peter Kirk Park and Lake Washington beyond.

To tie the uses of the site together, architects threaded through the site a woonerf—a “living street” mainly for pedestrians here, but also allowing light auto traffic and short-term parking—from Central Way at the northeast down to Peter Kirk Park on the west. About 50,000 square feet (4,600 sq m) of retail space flanks the woonerf on the plaza level. In addition, about 14,000 square feet (1,300 sq m) of space is occupied by a Bright Horizons preschool, which has an outdoor play area on the main plaza level above the QFC underground loading facilities.

The site plan shows the mixture of uses at the lowest level, with the QFC grocery loading and service areas located underground, below a plaza that contains an outdoor play area for a daycare center. About 50,000 square feet (4,600 sq m) of retail space is located on the plaza level flanking a woonerf that ties together the apartment, office, and retail components.

Office Component

The office space is divided into four buildings—Urban North, Central, South, and East. Urban North and Central were completed in 2019, and Urban South will follow in 2022. Urban East will be the last phase of the project developed.

Leedom said there were “several reasons to divide the office component into several buildings—view corridors, what we felt were correct floor plates given the likely tenants, input from QFC on their store size, existing tenants on the site during the construction of phase one, the necessity to keep the older QFC store open, and risk of building more space than could be absorbed at once.” The office buildings are seven- to eight-story, post-tensioned concrete structures, reflecting the size of development risk the venture wanted to take on, notes Leedom. Later, a skybridge between the Urban Central and South buildings will be added to connect Google workspaces.

Talon was able to prelease about half the office space in the Urban North and Central buildings, Leedom says, with two leases to technology companies. Seattle business-intelligence company Tableau Software, which develops data-visualization software, leased three floors totaling 92,000 square feet (5,800 sq m). Kirkland-based internet provider Wave Broadband, which builds fiber optic infrastructure, signed a 10-year lease to occupy 88,000 square feet (8,200 sq m) in one of two eight-story towers. When Wave was bought by San Francisco private equity company TPG Capital, it worked with owners to terminate its lease in 2018 so Google could occupy Wave’s former premises. With half the office space for its first phase pre-leased in 2015, Talon was able to access debt markets to begin demolition and construction, says Leedom.

Although PGIM had intended the project as a long-term-hold investment, in fall 2019, Google bought all of Kirkland Urban, its then two mixed-use office buildings, two retail buildings, and parking garage, minus the 185-unit Uptown apartments, for $400.7 million (based on a real estate excise tax report) in addition to another $35 million for a two-acre (0.8 ha) parcel on which Urban East is to be built. In December 2019, the entitlement to build another 115 apartments was transferred to office space, bringing the total allowed office space to 925,000 square feet (86,000 sq m). If average office space per employee is calculated at 150 square feet (14 sq m), that would provide space for as many as 6,000 employees.

Comfort and efficiency drove additional innovation. Variable refrigerant flow (VRF) mechanical systems were used to help achieve a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold rating. VRF systems are ductless and use variable-speed motors to deliver precise amounts of refrigerant to zoned heat exchangers that provide either heating or cooling to different parts of the building, increasing comfort for tenants and reducing expenses for owners.

Retail Component

The 165,000-square-foot (15,000 sq m) retail component was initially driven by the city’s requirement that the developer build one square foot of retail space for every four square feet of the 650,000-square-foot (60,000 sq m) office component. With the commitment of QFC to double its store size to 50,000 square feet (4,600 sq m) and iPic to lease a 54,000-square-foot (5,000 sq m) cineplex for a dine-in-theater concept, a significant percentage of the requirement was met.

Apartment Component

The 185-unit apartment building called Uptown at Kirkland Urban, at the highest corner of the site at Central Way and Sixth Street, is a five-story wood-framed structure over a concrete podium. Roof decks look over Lake Washington and Seattle in the distance. Talon codeveloped the apartments with Minneapolis-based Ryan Companies US Inc.

The unit mix is 26 percent studio, 47 percent one-bedroom, and 27 percent two-bedroom/two-bathroom apartments. Many of the two-bedroom units are two-story lofts. The apartments range from 481 to 1,406 square feet (45 to 131 sq m), and rents range from $1,950 to $4,645 per month. Rents for the unassigned garage parking range from $90 to $125 per month.

Shared Parking

Only mixed-use development programs can create the opportunity to share parking, increasing the efficiency of each expensive stall and reducing the total parking needed to support a more intensive use of the land. The predominant use in this program mix is office space, which requires one space for each 350 square feet (33 sq m)—a 2.86:1 parking ratio of spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 sq m) under the city zoning code. Restaurants require an 8:1 ratio under the code, and apartments a 1.38:1 blended ratio based on Uptown’s unit mix. The total number of parking spaces under the code for that program was 3,747.

But actual parking demand in a mixed-use project varies by use, time of day, day of the week, and by season. If a developer can reasonably project actual demand according to those factors, the quantity of parking needed can be substantially reduced.

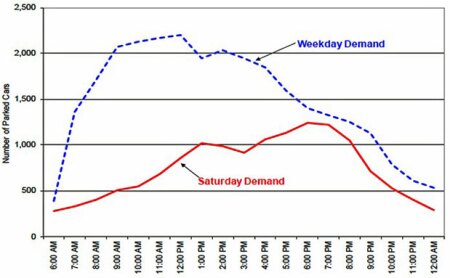

Leedom hired Seattle-based Heffron Transportation to forecast parking demand and needed supply. Heffron projected a maximum cumulative peak parking demand of 2,287 cars at noon on a weekday at full buildout, including a 377-space reserve supply for commercial and residential uses. That represents a difference of 1,460 parking spaces between the code-required spaces and the projected maximum demand, a potential cost savings of $65.7 million in development costs. Even under conservative assumptions, that equates to a 1.7:1 weighted parking ratio versus the 2.8:1 parking ratio required by code without consideration of shared parking.

Kirkland Urban retains a third-party parking manager to manage parking for maximum efficiency. A reserve parking supply of 15 percent vacancy is targeted to reduce the time a customer must circulate to find an open space. Price is also an important factor. Retail parking at Kirkland Urban is free for four hours with a validated purchase. Otherwise, daily parking costs range from $5 to $35, depending on duration. Monthly parking is $125.

Office parking is also allocated. “Office parkers have their own access cards, and with our garage parking system you can see if an office tenant has gone over their allotment by number of cars and charge for that as appropriate per their lease,” Leedom says. Of the spaces provided, 135 are reserved for apartment use and rented unassigned to residents. “We have a parking management company, gate arms, and ticket system to make sure everybody is playing by the rules of our parking easement, which is on the title as part of the condominium declaration,” he says.

The mix of uses in the development program is paramount in determining the efficiency of shared parking. Even if parking were built to maximum capacity for periodic weekday noon peaks of 2,287 spaces, and for 7 p.m. Saturday weekend demand peaks, only 1,200 spaces would be needed for evening and weekend users, leaving 1,087 spaces vacant. That suggests that, if market demand existed, more than 1,000 hotel rooms could be developed with no additional spaces required, even assuming a liberal parking ratio of one space per unit.

Traffic engineers forecast a maximum cumulative peak parking demand of 2,287 cars at noon on a weekday at full buildout, including a 377-space reserve supply for commercial and residential uses. The difference between the 3,747 code-required spaces and the actual maximum demand of 2,287 was 1,460 parking spaces, representing a potential savings on construction costs of $65.7 million. (Heffron Transportation )

Surban Prototype

Kirkland Urban suggests that a new breed of developers is creating mixed-use surban prototypes at a more intensive scale, on sites larger than most urban projects but smaller than most suburban projects, and with uses more mixed and integrated physically and functionally than either of those others.

In many ways they are more complex than either. Building different uses on top of common parking requires careful planning of such things as structural bay sizes and plumbing chases.

But the benefits of such surban projects can outweigh their costs and complications. Places with on-site offices, apartments, groceries, restaurants, brew pubs, wine bars, and theaters offer a greater level of urbanity than single-use urban or suburban projects. That urbanity can drive premium rents and lower vacancies. Contiguous floor plates of integrated parking that serve many uses are occupied during more hours of the day and week than their single-use counterparts. That greater efficiency reduces the total amount of expensive structured parking necessary, supports more intensive use of the land, and increases development value—and with it the tax base of the town. Kirkland Urban’s taxable value, excluding the 1,706-space parking structure, was $315 million at the completion of its first phase.

WILLIAM P. MACHT is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University in Oregon and a development consultant. (Comments about projects profiled in this column, as well as proposals for future profiles, should be directed to the author at [email protected].)

Shared Parking, Third Edition, published by ULI, ICSC, and the National Parking Association, is available in paperback ($155.95) or with Excel model ($649.95) at bookstore.uli.org.

Recent Articles by William Macht:

- Solution File: Courtyard House Clusters Offer Post-Pandemic Appeal

- Drones for Development

- Solution File: A City Center at the Fringe

- How to Build Livability—and Value—on a Deep, Narrow Infill Lot

- Bringing Mixed Uses—and Open Space—to a Multiple-Small-Block Development in Portland

- The Rise of Pop-up Hotels