A spate of recent global crises—including the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and rising rates of inflation—have forced hospitality practitioners to rethink their development models. This is particularly true for the development of all-inclusive resorts (AIRs) in culturally or ecologically sensitive areas. One such area is Lac Rose—a prime tourist destination in Senegal and a choice location for hotels chains looking to expand in the African continent.

My group, Adanson Hotels & Resorts, had long been interested in developing an AIR in the Lac Rose region; however, in the wake of the pandemic, our plans shifted drastically. Our experiences with Lac Rose may be instructive for other developers, investors, and local governments who are interested in rethinking traditional development models by analyzing them within a framework of environmental sensitivity, social responsibility, and impact investment.

Tourism has been growing rapidly in Senegal since the 2000s and has become one of the most potent industries within the country. The tourism sector employs approximately 150,000 people, and the country has seen a steady growth in the number of yearly inbound international tourists, rising from 200,000 in 1996 to 1.4 million in 2016. The number of hotels in the country stands at 250, split almost evenly between two customer segments: the international beachfront resort customer, and the meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE) international customer.

To some international tourism consultants, like Horwath HTL in their 2018 Senegal Tourism report, Senegal’s hotel market is one of the best performing in sub-Saharan Africa because of its “pipeline of internationally branded hotel projects more adapted to international standards.” According to that 2018 report, international brands such as Hyatt, Sheraton, and Club Med were planning to dramatically increase their presence in Senegal over the next five years. Post-COVID, Club Med abandoned some unprofitable sites, but Marriott and other local operators remained very bullish on the sector.

Within Senegal, the Lac Rose region is a prime tourist destination and popular resort area. Located approximately 15 miles from Dakar, the lake is one of only three pink lakes in the world. A species of red pigmented algae that thrives in salty waters is the cause of the lake’s unusual bubble gum color. This picturesque natural feature contrasts vividly with the bright yellow desert-like sand dunes and pristine white sand beaches surrounding the site.

The lake is approximately 1.1 square miles (2.85 km sq) and is on the short list to be classified by the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a World Heritage Site—a testament to the location’s special physical and cultural significance to the world. The site was also the traditional finish line of the famed Paris-Dakar Rally, an off-road endurance race, before security concerns led to the event’s cancellation in 2008 and its later move to South America. For Adanson, this unique location seemed like the perfect place to launch the group’s first hospitality venture in Africa.

The Lac Rose project was very important to Adanson’s growth strategy as it represented the first of many planned projects on the Atlantic coast of Africa from Dakar to Cape Town. The group’s preference was to operate in the all-inclusive sector because that sector has seen tremendous growth in recent years. According to Smith Travel and Research, AIRs generated $7.9 billion in sales through the first six months of 2019, a 20 percent increase in revenue from five years earlier. Smith Travel’s data tracks 1,500 AIRs globally, the vast majority of which are small independent operators who lack the brand recognition of international chains like Marriott. Adanson was betting that the all-inclusive sector would attract the attention of traditional hotel brands like Marriott and Hyatt who want to enter a space that is still currently dominated by independent and regional chains. Adanson’s ultimate goal was to develop enough scale and brand recognition in the region to eventually join forces with a larger hotel group.

Exacerbating Inequality

An AIR, or all-inclusive resort, can be defined as a resort where everything is prepaid in advance: transportation, accommodation, food and drinks, sightseeing, and entertainment. They tend to be built in scenic-yet-remote locations that may have little pre-existing infrastructure and local populations that are economically vulnerable.

Because of their locations, AIRs represent a classic negative externality problem. In economics, an externality is a side effect of commercial activity that affects third parties, but that is not reflected in the cost of the goods or services. All-inclusive resorts often create negative externalities by driving up the cost of land and damaging the environment in these rural locations. In the case of Senegal, AIRs often sequester visiting tourists’ cash, leaving very little for the surrounding communities. This creates a sort of hospitality revenue leakage—that is, money leaving or bypassing the host economy. If not properly contained, this revenue leakage may leave local populations in a worse-off economic situation, as they face the frustration of seeing their built environment being transformed by the development of airports, roads, and resorts, while not being able to participate in that growth themselves.

One particularly pernicious side effect of revenue leakage is that the increased economic pressure on local populations can lead them to abuse or over exploit their natural environment. For example, Lac Rose has seen its size reduced by a factor of 10—from 32 km in 1980 to approximately four km today—due to over-extraction of the prized salt that gives the lake its distinctive pink color. The local population, having not seen many trickledown benefits from nearby hotels and the tourism infrastructure (conference centers, airports, train stations) that supports those hotels, has instead been forced to extract and sell increasing amounts of salt as their only means of avoiding severe poverty. The more salt that is extracted, the more the lake shrinks.

Despite these concerns, Adanson embarked in 2015 on the development of the Lac Rose site into a traditional mixed-use project anchored by a 200 key luxury all-inclusive hotel and a 100,000 square foot (9,290.3 m sq) conference center. At the time, our sole focus was to make as much profit as possible given the risk that we were taking by investing in a developing country. Our project market feasibility study pointed to solid financial returns but also highlighted some potential environmental challenges that had to do with the resiliency of the site itself. Issues such as flood protection, erosion control, wildlife habitat protections, and safety networks for energy and food supply networks would have to be mitigated. Nevertheless, we were confident that we could overcome these hurdles and make money by focusing on operational efficiency and seeking partnerships with bigger hotel operators like Marriott and Hyatt.

Project Hits Roadblock

By January 2020, however, the Lac Rose project had hit a roadblock. With the rise of COVID-19, hospitality had become one of the least attractive types of investment opportunities globally, and many of our investors were backing out. At the time, it was predicted that the hospitality industry could be facing a sustained systemic shock and might take years or even decades to recover to pre-pandemic levels. While those fears ultimately did not materialize, other concerns have arisen. Climate change and sustained global inflation threaten the long-term viability of the AIR model. Even companies that are known for their operating efficiency are facing higher operating costs and interest rates due to sustained inflation and increased environmental regulations from the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC’s green disclosure plan could require real estate firms to disclose greenhouse-gas emissions and reduction targets, as well as transition plans. It was clear that Adanson needed to rethink our focus on the AIR model.

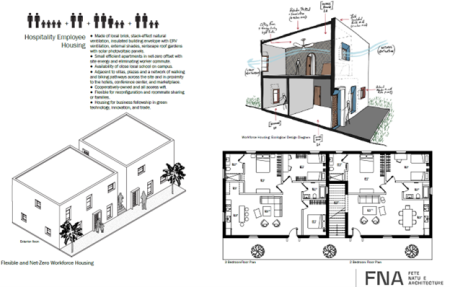

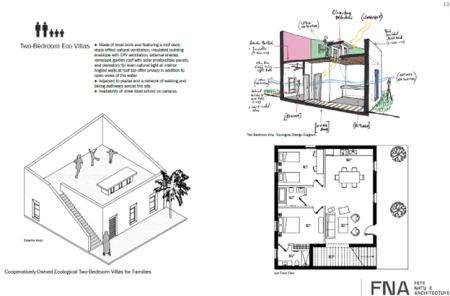

We hit pause on the Lac Rose project and went back to the drawing board. This time, we focused our redesign and our value proposition around a simple mission statement: “Delivering value through values.” Part of our inspiration was the desire to enter the August 2020 Hospitality Challenge, an annual competition organized by the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). The theme of that year’s competition was to develop a new business model for the hospitality industry post COVID-19 pandemic. Our submission for the competition was a revised version of the Lac Rose project, including a pristine mix of two- and three-bedroom ecolodge villas (see below), a hotel positioned in the midscale segment, a sustainability-focused conference center, an incubator/accelerator school focused on educating a new crop of local craftsmen and entrepreneurs, and a workforce housing complex. For the conference center, we planned to seek EDGE green certification, reflecting our commitment to a low carbon footprint design.

In addition, we committed to proactively developing and hosting programming at the conference center that would focus on seeking solutions to problems that affect the local community. For example, we mapped out our first conference on tackling the topic of unsustainable salt extraction in the Lac Rose region, an issue that has threatened the survival of Lac Rose and its future as an UNESCO World Heritage Site. We also explored a conference on the Great Green Wall, an ambitious project to build an 8,000-kilometer-wide wall of planted trees across Africa—spreading from Senegal on the Atlantic Ocean to Eritrea on the Red Sea. If implemented well, the Great Green Wall would reduce droughts, famine, and desperate attempts of jihadization by young Africans. Conference participants would be able to see firsthand the progress so far by visiting the Senegalese portion of the wall.

Thinking Local

While our Lac Rose project did not win the Hospitality Challenge, the work we put into preparing for the competition had a lasting impact on our firm. Our focus had shifted from a classic AIR setup towards increasing local content, minimizing our environmental footprint, and reducing revenue leakage as much as possible. However, one very important piece of this new vision was missing: finding likeminded investors. The success of values-based projects depends on finding patient capital that thinks beyond a single bottom line metric of a development’s success, such as the famed yield on cost (i.e., stabilized income divided by total project cost). These types of investors recognize that a successful real estate development requires an integrated approach that can no longer be isolated to the simple asset itself.

One example of such an investment in hospitality is the Hoxton Hotel in London, where the lead investor was Bridges Ventures Sustainable Growth Fund—a fund that aims to achieve both positive financial returns and social and environmental benefits. The redevelopment of the Hoxton by Bridges Ventures delivered an internal rate of return of approximately 47 percent upon exit and 8.8 times the initial investment, while at the same time regenerating a blighted area and making sure that over 70 percent of the hotel staff live in underserved areas.

Another example of impact investing in hospitality is Beartooth Capital, which targets ecologically sensitive land and adds value by increasing the land’s worth through restoring environmental damage and conservation. Their strategy is unique in that after restoring the land, the firm’s exit strategy depends on finding a likeminded buyer whose use of the property will not disrupt the conservation benefits already acquired. This search may require Beartooth to hold the property longer than a traditional investor would because their exit does not depend solely on interest rates or other traditional real estate factors. Beartooth’s investment strategy can be viewed as creating positive externalities, as their commitment to conservation creates spillover benefits for everyone.

Even though Beartooth and Bridges Venture work primarily in developed markets, applying these same types of models at sites like Lac Rose and in other developing regions would help avoid many of the negative externalities of hospitality development, particularly those created by AIRs. Whether in the United States or in Senegal, the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and economic upheaval has underscored the need for a new model for hospitality—one centered on minimizing environmental footprint and increasing social responsibility, while sourcing capital from impact investors.

If adopted more broadly, this new model could reduce revenue leakage by investing in local human capital alongside roads, airports, and other more traditional forms of infrastructure investment. It could also reduce the hospitality industry’s carbon footprint through ecologically sensitive planning and execution of projects, which could in turn eliminate the vicious cycle of populations over-exploiting the very natural environment that they depend on for their survival. Long term, we believe that an increasing focus on sustainability, social responsibility, and impact investing will be key as the hospitality sector adapts to a world in transition.

SEYDINA FALL is a senior lecturer at Johns Hopkins Carey Business School.

A submission for the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization Hospitality Challenge was a revised version of the Lac Rose project, including a pristine mix of two- and three-bedroom ecolodge villas, a hotel positioned in the midscale segment, a sustainability-focused conference center, an incubator/accelerator school focused on educating a new crop of local craftsmen and entrepreneurs, and a workforce housing complex.

![Western Plaza Improvements [1].jpg](https://cdn-ul.uli.org/dims4/default/15205ec/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1919x1078+0+0/resize/500x281!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fk2-prod-uli.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Fbrightspot%2Fb4%2Ffa%2F5da7da1e442091ea01b5d8724354%2Fwestern-plaza-improvements-1.jpg)