A San Francisco project suggests that linking separate problems then integrating their solutions can lead to optimal results.

Developing modern buildings adjacent to historic icons can present unique challenges—especially in an area of downtown San Francisco with an active historic preservation community. Transferring additional floor/area ratio (FAR) development rights to increase the area and height of a new building to a level proscribed by mandate can increase the burden on developers even further. But, counterintuitively, developer One Kearny LLC solved the puzzle of a San Francisco site by choosing to integrate a historic building with its modern neighbors to create a single structure with three parts.

The site was originally known as Newspaper Angle for its eccentric geometry and its position as home to the city’s major turn-of-the-century newspapers—the Chronicle, the Examiner, and the Call-Bulletin. Their owners, Michael deYoung, William Randolph Hearst, and Claus Spreckles, competed to erect the most striking building at the intersection of Market, Geary, Third, and Kearny streets.

DeYoung built first—the Chronicle Building, designed by Chicago architecture firm Burnham and Root in 1890—followed by Spreckles’s Call Building in 1902 and Hearst’s building in the early 1920s. On the fourth corner, the Mutual Savings Bank, designed by William Curlett in the French Renaissance revival style, was constructed in 1902. The ornate bank building sits at the end of Third Street, a major automobile and bus approach to San Francisco’s retail and financial centers. Stone clad and topped with a prominent orange-tiled mansard roof, its steel frame was designed and provided by the Roebling Company, which designed the Brooklyn Bridge. The building withstood the 1906 earthquake and sustained relatively modest damage from the ensuing fire, rendering it somewhat sacrosanct among historic buildings.

In the early 1960s, the bank’s owners wanted to demolish the building to make way for a modern structure, but a young architect, Charles Moore, argued for saving it. He prevailed and designed an addition—now called the Annex, containing new elevators and a fire stair—as an adjunct to the bank building, following a concept postulated by architect Louis Kahn, under whom he had studied. Moore, who went on to become dean of the Yale School of Architecture, capped the otherwise modernist Annex with a historicist flourish—a gesture to the original mansard roof.

The current owners bought the 12-story, 68,500-square-foot (6,400-sq-m) bank building and the 13,700-square-foot (1,300-sq-m) Annex in the early 1990s, after it had been converted into a commercial condominium with a mix of uses, including a ground-floor bank, offices, and a residential unit under the mansard roof. They then acquired an adjacent, flanking three-story building that had been altered a number of times since its construction in 1908. It was the chipped tooth in the street wall along Market Street, where most buildings were ten to 12 stories tall.

The objectives of the owners were different from those of the city. The owners wanted the $40 million project to maximize the rentable floor area and views, to make the space more flexible to allow multiple tenants per floor, and to provide view space at the core corner. The project had to reconcile the preservation community’s concern for historic continuity with the planning department’s interest in promoting contemporary development that is integrated into the historic fabric. In addition, seismic strengthening of an early 20th-century landmark was of paramount importance.

Several factors complicated these challenges. The two parcels to be joined were in separate zoning districts with differing FAR limits—6:1 versus 9:1—and the new site had been down-zoned based on voter approval of Proposition M in 1985, reflecting antigrowth sentiment and residents’ fears that the city was becoming too much like Manhattan. The 1985 down-zone limited height to 140 feet (42.7 m), almost 50 feet (15 m) shorter than the top of the mansard roof. In addition, a section of the San Francisco planning code restricted building mass to avoid significant shadows being cast on Geary Street, to the north of the property.

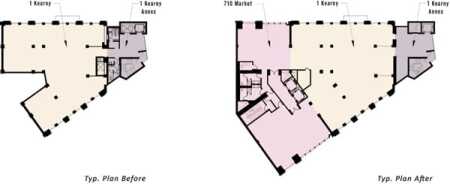

Structurally, the two existing buildings had incompatible capacities for seismic resistance. The 1964 Annex is much stiffer than the 1902 building and had been structurally isolated from it so as not to shake it to pieces in an earthquake. This isolation left structural capacity of the Annex unused. The concentration of core elements in the Annex also blocked views down Market Street to San Francisco Bay, and the elevator lobby was too big for the 4,000-square-foot (370-sq-m) floor plate it served. A bottleneck between the Annex and the original building—caused by city-mandated separation walls between exit stairs and the elevator lobbies—made creation of multitenant floors especially difficult.

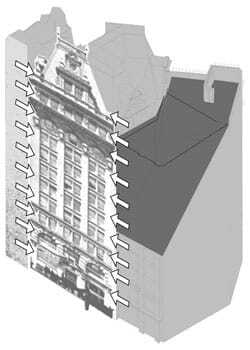

San Francisco–based architect Charles F. Bloszies, who is also a structural engineer, devised a synthesis of structural and spatial goals. He proposed relocating the elevator core from the Annex to the new western building and using the new structure, in combination with the stout 1964 eastern Annex, to form seismic bookends that would strengthen the original 1902 building with almost no architectural impact.

The result would tie the three buildings together for better seismic resistance, preserve the historic building, open the interiors to form a single floor plate for multiple tenants, and free the prominent corner to embrace the city. The bookend buildings were attached to the floor plates of the original historic building by cutting back the original slab a few feet and then inserting dowels between the new slab and the original, which is secured to the original steel framing. Front-to-back movement is resisted by shear walls, and no new vertical bracing elements were needed in the original structure.

However, for the seismic bookends to work, the new addition would have to rise to the eaves of the 1902 building, making the new bookend as tall as the center, thereby exceeding the 140-foot (42.7 m) height limit and shadow plane setback. Increasing the height limit to the necessary 150 feet (45.7 m) required a zoning reclassification. Increasing height would push the building over the maximum allowable 6:1 FAR on the new parcel, so the lot needed to be rezoned and merged into the same district occupied by the original Mutual Savings Building, where the more generous 9:1 FAR prevailed.

Furthermore, the owners had to purchase transferable development rights (TDRs) to develop the additional, tenth story. Stepping the building back to comply with the prescriptive shadow plane mandate would also have prohibited the bookend from bracing the historic building at crucial points. The owners commissioned a study, which demonstrated that a ten-story building flush with the street wall would not result in a significant shadow. The city accepted the study and allowed the new structure to be constructed to the lot line, the bookends were allowed to brace the 1902 building, and the development’s rentable area was increased by over 5,000 square feet (465 sq m). The structural strategy both maximizes the amount of rentable area—now 115,605 square feet (10,740 sq m) of the total 137,000-square-foot (12,700 sq m) gross area, according to Building Owners and Managers Association standards—and achieves 85 percent net-to-gross space efficiency.

The project needed to comply with the strict historic guidelines mandated for San Francisco’s Kearny-Market-Mason-Sutter Building Conservation District. Moore’s Annex had attained historic significance despite its relative youth as the project went through the San Francisco entitlements process. Yet, the juxtaposition of two distinctly different historic structures excluded an architecture response that would simply extend one or the other of the two styles.

To respond to the two very different architectural precedents, the new addition’s curtain wall picks up the rhythm of the 1902 facade, and the internal seismic frames are expressed in strong vertical elements, mirroring Moore’s brick-clad Annex towers. These elements are clad in a terra-cotta rain screen, a contemporary version of a traditional material. The classical composition of the new facade—base, shaft, and capital—echoes that of the original French Renaissance revival style. San Francisco–based historic preservation architect Page & Turnbull directed the restoration of the 1902 facade. Both the San Francisco Landmarks Board and the Planning Commission approved the design with only minor comments.

Often, when developers face multiple problems, they choose to separate and solve them independently. In the One Kearny project, a single strategy of linking separate problems, then integrating their solutions, suggests that addressing them together can lead to optimal results.