Weighing racial disparities in the commercial real estate industry.

The Urban Land Institute’s British Columbia district council is among a group of five ULI district councils that have been working to examine local histories of racial discrimination in land use and transportation, to draw connections with current health equity disparities, and to chart a course towards a more equitable future for the real estate industry. The project, ULI District Council Partnerships for Health Equity, is supported by the ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative with financial support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

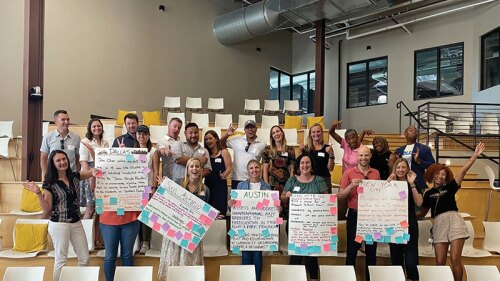

The cohort of participating district councils includes ULI Houston, ULI St. Louis, ULI British Columbia, ULI Northwest, and ULI Toronto. The project launched last year, following an open call for interest from North American district councils. The district councils are working in partnership with other organizations locally to understand historic inequities and racial discrimination in land use, and to craft creative strategies to address the ongoing impacts of these policies on community health and wealth disparities. These action agendas for change in real estate will emphasize tangible steps for real estate, in addition to broader policy recommendations.

The ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative works to make health and social equity mainstream considerations in real estate practice. According to William Herbig, senior director of the ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative, “The two main factors driving this reckoning within the industry and within ULI include the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color and those of low income; and the rise of the racial justice movement as a result of the brutal murder of George Floyd.

“ULI, as an organization, has committed to doing more,” Herbig says. “Our profession has been part of the problem. We have the ability and the responsibility to address racial inequity going forward. But we cannot go at it alone. Finding solutions requires building new bridges of trust and cooperation beyond our network of members.”

That the district council teams are geographically diverse was intentional. And this marks the first time a Building Healthy Places program has been able to fund councils in Canada. “The systemic racial issues are different in the U.S. versus Canada, and there’ve been robust listening and learning opportunities amongst the two Canadian teams and the U.S. teams to better understand nuances involved in Black and Indigenous experiences and differences in the two countries,” Herbig says Each district council has identified chairs and a leadership group for the effort.

The aim of this program is to “address these systemic issues,” Herbig says. To do so, the ULI district councils are reaching beyond their established local networks, forging new relationships, learning about local histories, and working to drive fundamental industry change.

Breaking Down Housing Barriers in Indigenous Communities

Learning from the past is at the crux of ULI British Columbia’s focus. That district council aims to facilitate research to help provide solutions for the development community to “break down the barriers to housing and other factors that have historically been obstacles for Indigenous health and success,” according to Sheryl Peters, provincial director of redevelopment at BC Housing.

Serving the Indigenous population comes with a specific set of challenges. Understanding all that is involved will be key to overcome barriers and provide stable housing options.

“When we think about the Indigenous community, all 204 Indigenous groups, every nation has unique languages, cultures, art, and design and housing needs,” Peters says.

The Indigenous community in Metro Vancouver includes three First Nations. They are: xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, (Musqueam Indian Band); Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, (Squamish Nation); and səlilwətaɬ, (Tsleil-Waututh Nation), according to Peters. In addition, there are other urban indigenous communities.

“There is diversity within those groups,” says Duncan Wlodarczak, who chairs ULI British Columbia. “People approach them as being relatively monolithic, and you can’t do that.”

As in the U.S., an affordable housing crisis exists in the area, according to Kaela Schramm, director of projects and planning at M’akola Development Services, an Indigenous not-for-profit organization and development consulting firm. “For this particular project, we’re looking at the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and affordable housing in the Metro Vancouver area. Specifically, we’re working to identify many of the barriers impacting equitable access to this much-needed housing and are developing tools the local real estate sector can use improve access to safe, affordable and appropriate housing that can promote increased health, well-being, and long-term social sustainability.”

To be successful, it is necessary to acknowledge the past while also working to understand the present, Schramm says. Historical events must be addressed to begin laying the groundwork for how best to remedy past wrongs and help the Indigenous community now.

“The intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples continues to ripple though communities, families, and individuals in profound ways, and part of the challenge for us working in this space is to continue to find ways to walk beside our Indigenous neighbors, shoulder to shoulder our shared path toward reconciliation,” says Schramm who is also a community ambassador.

For more than a century, the primary goals of Canada’s policy on Indigenous peoples were to eliminate Indigenous governments, ignore rights, terminate the treaties, and, through assimilation, cause Indigenous peoples to cease to exist as distinct social, cultural, and legal entities within Canada, Schramm says.

“Tragically, Indigenous children were often the main target in advancing this policy,” says Schramm. The last federal government-supported “residential school” system closed its doors in 1996 with an estimated 150,000 Indigenous children taken from their families, from their communities, and from their cultures.

The Province of British Columbia and the Government of Canada continue to work on reconciliation strategies as do innumerable community-based agencies, but Schramm notes there is still a great deal of work to do.