Two recent additions to the ULI Case Studies series highlight the possibilities a city’s historic building stock offer to multifamily developers with a special interest in revitalizing urban neighborhoods through a blend of old and new.

Sofia Lofts in San Diego and Mercantile Place in Dallas mix historic rehab with new construction, modern design principles and amenities, and large common areas. In both cases, the result is a strong, well-defined sense of place and a highly sought-after rental community accessible to or in the heart of downtown. Both projects make creative use of existing properties to build up residential density within the urban core.

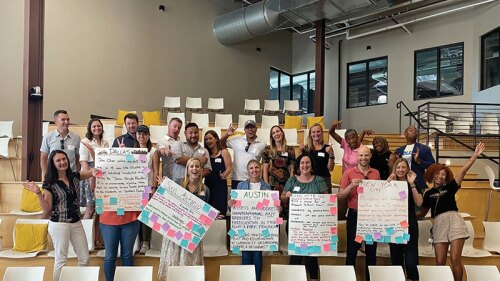

A significant difference between these two developments is scale. Sofia Lofts has 17 units and offers a mix of newly constructed duplexes, flats, and studios, all anchored by a 1920s-era three-bedroom home that has been repurposed as boutique tech office space. Mercantile Place, spread across three office-to-residential conversions and one newly constructed apartment building, consists of just over 700 apartments, ranging from studios to two-bedroom units that come in a variety of sizes and floor plans. The result of a public/private partnership, Mercantile Place has played a significant role in reviving the east side of downtown Dallas. During a recent ULI webinar, members of each project’s development team shared their approach, vision, and process behind integrating 20th-century architecture into innovative spaces designed for a 21st-century lifestyle.

Sofia Lofts: Small-Scale, Urban-Infill, Sustainable Design

Sofia Lofts is a classic example of a small-scale, urban-infill development trend that is returning vacant and underperforming land and property to productive use across the United States. In San Diego, land availability is constrained by natural geographic boundaries—the Pacific Ocean to the west and mountain ranges to the east—as well as built ones, the U.S.-Mexico border and Camp Pendleton.

Infill sites in established neighborhoods provide the greatest opportunity for new development, said Soheil Nakhshab, developer of Sofia Lofts and principal of Nakhshab Development and Design (NDD) Inc.

“Our target is urban, infill sites,” he said. “In these beautiful metropolitan neighborhoods, there is so much character and culture. They are waiting to be revitalized.”

In the case of Sofia Lofts, a three-bedroom bungalow, built in 1928 and located a mile (1.6 km) from downtown San Diego in the Golden Hill neighborhood, showed up on Nakshab’s radar during an online property search. NDD purchased four separate parcels attached to the home to assemble the 0.41-acre (0.17 ha) site and built two, eight-unit apartment buildings that flank the historic home.

Nakshab and his business-partner brother Nima wanted to re-create the feel of a family compound or multigenerational household such as they were accustomed to seeing in their native Iran and experiencing within their own family. A family could move through its life cycle in Sofia Lofts, initially occupying the duplex then downsizing to a studio once children were raised and had moved on.

The Nakshabs envisioned a series of modern, private residences situated around a common courtyard that serves as a focal point and gathering place. “In a typical apartment complex, you are very disconnected from your community and other residents,” said Soheil Nakshab, who took part in the webinar. “We wanted all the units to look out at this central courtyard, which becomes a key amenity to the site.”

The courtyard features a fire pit, an outdoor screen for movie nights, and grills and picnic tables for barbecues. Expansive windows flood the apartments with light, yet are strategically placed so that none is within another unit’s direct line of sight. Personal safety was also a priority in the design. “You can see neighbors constantly coming and going. You’re keeping an eye out for one another,” Nakhshab said.

Nakhshab originally intended an exclusively residential use for the bungalow, which went through a gut rehabilitation. But when Cursive Labs, a technology incubator, approached the company about renting the bungalow for its office, Nakhshab liked the idea.

“The beauty of having [Cursive Labs] is the constant presence on the site and constant stimulation” of the courtyard through employees having lunch, holding business meetings, and even using the outdoor screen for presentations. “It’s interesting to see how [Sofia Lofts] has evolved into a mixed-use environment on its own.”

In addition to the sleek, modernist design of the new buildings and the site’s accessibility to downtown, Sofia Lofts’ sustainability features have been a huge selling point, according to Nakhshab. The project is certified Platinum under the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, offers Car2Go vehicle sharing, bike sharing, and bike storage on site. Not all 17 units have dedicated parking spaces, and some spaces are reserved for nontenant use. All units have a single bathroom to reduce the consumption of water, a precious commodity in drought-prone California.

The state’s building code requires all new buildings to meet strict energy efficiency standards; Sofia Lofts exceeds those standards by at least 30 percent through high-efficiency fixtures, passive cooling and heating, and a well-sealed building envelope, Nakhshab said, because NDD was looking to provide long-term sustainability. NDD also took advantage of a state rebate program that paid 60 percent of the cost of the project’s solar panels.

Mercantile Place: Key Player in Renaissance of Downtown Dallas

Forest City Enterprises—now known as Forest City Realty Trust—arrived in Dallas in the mid-2000s at the request of former Mayor Laura Miller, who was seeking a real estate partner experienced with large-scale urban revitalization projects. The city was willing to make significant public investments in the right project to achieve a catalytic impact, said James Truitt, senior vice president of Forest City Texas.

Miller and other leaders wanted to focus attention on the east side of downtown, which was lagging other downtown neighborhoods that had been undergoing a renaissance. As major companies migrated to north Dallas, several historic office towers on the east side were left vacant, including the former Mercantile National Bank building, built in 1942 and known colloquially as “the Merc.”

The 31-story art deco building and other structures the bank had owned covered three city blocks, providing ample opportunity for an experienced developer to do something big. Forest City saw the chance to convert several vacant office buildings into housing, effectively creating a new neighborhood—what would become Mercantile Place—on the city’s east side.

What was required to execute this vision was rehabilitation of certain structures and demolition of others—all at significant cost, Truitt said. The city had established a tax increment financing (TIF) district in order to incentivize development in the area. For Forest City’s proposal, the city issued $57 million in bonds to support upfront development costs. In addition to $15 million in Forest City’s own equity and a $48 million loan, the TIF bond revenue constituted a significant portion of the $120 million capital stack that funded Mercantile Place’s first phase—the Merc, renovated to provide 213 apartments; the Element, a newly constructed, 153-unit apartment building; and the Jewel, a common area that provides access to the Merc’s mailroom, swimming pool, and fitness area.

The city stepped in at another crucial moment when Forest City’s application for historic tax credits was denied by the National Park Service. Forest City was able to preserve the Merc, but demolished about 1 million square feet (93,000 sq m) of space in adjacent historic structures that could not be saved. The city expanded the TIF boundary to compensate for the loss of tax credit financing.

The city’s interventions were “what made the deal happen,” Truitt said. Two additional buildings were incorporated into to the campus—the Wilson, a refurbished 135-unit loft building that had been converted from offices in 2000; and the Continental, a 1948 structure that the company rehabilitated into a 203-unit apartment building with a luxury spa, a new lobby, and views of Main Street Garden Park, a highly programmed urban park created in a former parking lot as part of the redevelopment. Twenty percent of the Continental’s units are reserved for those earning 80 percent of the area median income or less.

Undertaking a major, multiyear mixed-use project with complex financing requires an unwavering commitment from the public sector, Truitt noted. “Be sure you have a partner that wants to see urban development,” he said. “The city of Dallas has been a great partner.”

Learn more about Sofia Lofts and Mercantile Place on the ULI Case Studies website: casestudies.uli.org.