Weighing racial disparities in the commercial real estate industry.

A group of ULI district councils has been working to examine local histories of racial discrimination in land use and transportation, to draw connections with current health equity disparities, and to chart a course toward a more equitable future for the real estate industry. The project, ULI District Council Partnerships for Health Equity, is supported by the ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative with financial support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The cohort of participating district councils includes ULI Houston, ULI St. Louis, ULI British Columbia, ULI Northwest, and ULI Toronto. The project launched last year, following an open call for interest from North American district councils. The district councils are working in partnership with other organizations locally to understand historic inequities and racial discrimination in land use, and to craft creative strategies to address the ongoing impacts of these policies on community health and wealth disparities. These action agendas for change in real estate will emphasize tangible steps for real estate, in addition to broader policy recommendations.

The ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative works to make health and social equity mainstream considerations in real estate practice. According to William Herbig, senior director of the ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative, “The two main factors driving this reckoning within the industry and within ULI include the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color and those of low income; and the rise of the racial justice movement as a result of the brutal murder of George Floyd.

“ULI, as an organization, has committed to doing more,” Herbig says. “Our profession has been part of the problem. We have the ability and the responsibility to address racial inequity going forward. But we cannot go at it alone. Finding solutions requires building new bridges of trust and cooperation beyond our network of members.”

That the district council teams are geographically diverse was intentional. And this marks the first time a Building Healthy Places program has been able to fund councils in Canada. “The systemic racial issues are different in the U.S. versus Canada, and there’ve been robust listening and learning opportunities amongst the two Canadian teams and the U.S. teams to better understand nuances involved in Black and Indigenous experiences and differences in the two countries,” Herbig says. Each district council has identified chairs and a leadership group for the effort.

The aim of this program is to “address these systemic issues,” Herbig says. To do so, the ULI district councils are reaching beyond their established local networks, forging new relationships, learning about local histories, and working to drive fundamental industry change.

ULI British Columbia: Breaking Down Housing Barriers in Indigenous Communities

Learning from the past is at the crux of ULI British Columbia’s focus. That district council aims to facilitate research to help provide solutions for the development community to “break down the barriers to housing and other factors that have historically been obstacles for Indigenous health and success,” according to Sheryl Peters, provincial director of redevelopment at BC Housing.

Serving the Indigenous population comes with a specific set of challenges. Understanding all that is involved will be key to overcome barriers and provide stable housing options.

“When we think about the Indigenous community, all 204 Indigenous groups, every nation has unique languages, cultures, art, and design and housing needs,” Peters says.

The Indigenous community in Metro Vancouver includes three First Nations. They are: xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, (Musqueam Indian Band); Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, (Squamish Nation); and səlilwətaɬ, (Tsleil-Waututh Nation), according to Peters. In addition, there are other urban indigenous communities.

“There is diversity within those groups,” says Duncan Wlodarczak, who chairs ULI British Columbia. “People approach them as being relatively monolithic, and you can’t do that.”

As in the U.S., an affordable housing crisis exists in the area, according to Kaela Schramm, director of projects and planning at M’akola Development Services, an Indigenous not-for-profit organization and development consulting firm. “For this particular project, we’re looking at the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and affordable housing in the Metro Vancouver area. Specifically, we’re working to identify many of the barriers impacting equitable access to this much-needed housing and are developing tools the local real estate sector can use improve access to safe, affordable and appropriate housing that can promote increased health, well-being, and long-term social sustainability.”

To be successful, it is necessary to acknowledge the past while also working to understand the present, Schramm says. Historical events must be addressed to begin laying the groundwork for how best to remedy past wrongs and help the Indigenous community now.

“The intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples continues to ripple though communities, families, and individuals in profound ways, and part of the challenge for us working in this space is to continue to find ways to walk beside our Indigenous neighbors, shoulder to shoulder our shared path toward reconciliation,” says Schramm who is also a community ambassador.

For more than a century, the primary goals of Canada’s policy on Indigenous peoples were to eliminate Indigenous governments, ignore rights, terminate the treaties, and, through assimilation, cause Indigenous peoples to cease to exist as distinct social, cultural, and legal entities within Canada, Schramm says.

“Tragically, Indigenous children were often the main target in advancing this policy,” says Schramm. The last federal government-supported “residential school” system closed its doors in 1996 with an estimated 150,000 Indigenous children taken from their families, from their communities, and from their cultures.

The Province of British Columbia and the Government of Canada continue to work on reconciliation strategies as do innumerable community-based agencies, but Schramm notes there is still a great deal of work to do.

ULI Houston: Fostering an Equitable Vision with Settegast

Carolyn Rivera has lived in Settegast, part of Northeast Houston, for more than 40 years. She can recall the days when the “streets were passable” and the neighborhood was “beautiful” and “green,” but that is not how she would describe Settegast today. As a community ambassador for ULI Houston’s project, she is grateful that the team is focusing on improving her neighborhood.

“I’m glad that ULI is here, because that will make more noise, and that can eventually get the job done,” Rivera said.

The “job” is co-creating an action agenda for healthy community development in Settegast with residents and other stakeholders. The action agenda will include steps that residents, ULI members, local organizations, and local government can take to address community needs and work towards a collective vision of a healthy, opportunity-rich Settegast.

Initial steps to achieve this vision require addressing basic needs. Rivera and other Settegast residents have concerns about large swaths of vacant lots, illegal dumping, and drainage ditches that are not maintained.

Jessica Fuentes, another community ambassador, also describes the area’s lack of resources, with neighbors having to drive long distances to shop at a major grocery chain.

“It is a health problem for the community,” Rivera says.

Kyle Maronie, a current resident and the community engagement and empowerment manager for the Harris County Public Health Community Health and Violence Prevention Division is helping to connect his neighbors with the project’s core team. Maronie grew up in Settegast and purchased a home next door to his parents because of his commitment to see the neighborhood thrive for future generations and to help transform the narrative of the neighborhood.

“I don’t think folks are asking for anything that’s unreasonable.” says Maronie. “It’s the basic amenities that any community, anywhere, would want, including walkable streets, stopping illegal dumping. Just baseline development in the community would be transformative.”

The project, a partnership between ULI Houston, Harris County Public Health, Houston Land Bank, and The Kinder Institute for Urban Research is focusing on ways developers and organizations can address local concerns. The project team has collected extensive data from existing sources and new data from residents to provide actionable recommendations to key decision makers.

The goal is to thoughtfully engage with residents and developers to ensure residents can benefit from development without displacement.

ULI Northwest: Advancing Healthy, Community-Centric Growth

Tukwila in South King County, a suburb of Seattle, is a diverse, growing, immigrant-rich community that struggles with its reputation as a high crime area. It is one of two neighborhoods that ULI Northwest is setting its sights on for its ULI Building Healthy Places Partnership project.

ULI Northwest is joining with Healthpoint, a nonprofit health center, in Tukwila which is developing a new integrated wellness and health clinic. The area is extremely diverse but has little green space and bad health outcomes.

“We’re partnering with Healthpoint to put something in this location that really benefits the population and the community,” says Andrea Newton, executive director at ULI Seattle.

The team plans to provide technical assistance to help the more than 50-year-old clinic. They will incorporate what has been learned from the health center’s stakeholder engagement process and provide technical assistance to aid with the evaluation of potential multiple developer and partnership models, capital financing and sustainable operations.

“We want to put together an action agenda that can live in the annals of ULI to help guide developers and land use professionals as an approach to working collaboratively with communities,” Newton said.

They also plan to orient their partners at Healthpoint to building healthy places practices. The team is also now working on finalizing an additional project site in Portland. Team members are happy to begin to help address issues that have impacted local communities for decades.

“Each place has its own histories, and every place in America has a history of this white-led real estate industry and design industry that I am a part of, as well,” Seattle-based Partner with Mithun, and ULI Northwest Committee Chair Erin Christensen Ishizaki said. “I personally feel, while in the Northwest there’s been a conversation around racial and social justice for many years, I haven’t seen it come this directly into the real estate space until now.”

Ishizaki said it is clear work is being done within the public sector and the nonprofit sector. However, it is incumbent upon the commercial real estate industry to “step up and participate more actively within these initiatives, and more specifically try to combat some of that displacement,” she said.

ULI St. Louis: Amplifying the Physical and Mental Aspects of Housing Quality

ULI St. Louis is also reckoning with historical trauma as it aims to provide solutions for the lack of affordable housing citywide. While still early in the process, the team is striving to concentrate on “both the physical and the mental health aspects that seem most likely to be impacted by the quality of housing,” says Kacey Cordes, co-chair of ULI-St. Louis.

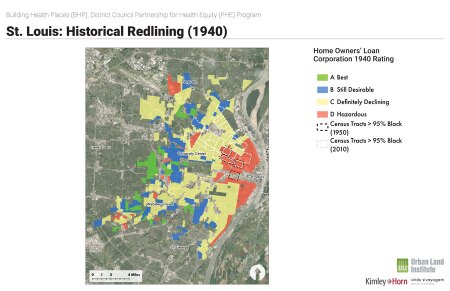

That team’s project focuses upon North St. Louis City, an historically Black neighborhood. Black residents lived here because of racially restrictive covenants and redlining. The ULI team aims to create an efficient network that can address home repairs in the area.

“One thing we’ve been talking about is how trauma is [among] our largest or most prevalent public health issues in America today,” says Aaron Williams, a team member, and a senior project manager at Penn Services. “We already know that vacancy is traumatic, and that displacement is traumatic, and one of the better preventative measures for both of those … issues is home repair. It mitigates vacancy, and it reduces displacement.”

The team aims to create an efficient network that can address home repairs in the area and is also connecting housing quality and current health conditions (via research that includes mapping mental health assessments and asthma).

The group aim to build a home repair network in St. Louis; members also hope to help raise awareness of the issue within ULI, according to Chip Crawford, ULI St. Louis co-chair.

In any city, a segment of the population is left out if there is no effective system in place to address deferred home repairs that disproportionately impact people of color, according to Cordes. When such a lapse occurs, people are relegated to having to choose between whether to repair or purchase a new roof, for example, or repair their staircase or replace their furnace, Cordes says, adding that this assumes they have the cash to pay for it and can find a willing contractor.

“If your city doesn’t have a robust home repair system, you can’t say you’re focused on racial equity in neighborhoods,” Cordes says. “You are permitting more trauma to happen, especially impacting children of color growing up in aging homes. Improving the health of our homes will help us succeed as a region.”

This team is not simply focusing upon ULI. It has its collective sights set on the bigger picture.

“The ULI group is important, but ultimately what we’re trying to do is effect positive outcomes in our community much more broadly than just [inside] the real estate industry,” says Kelly Annis, ULI St. Louis staff member.

ULI Toronto: Tracking Historical Displacement of Black Communities

Racial displacement is not confined to the United States. Toronto has also experienced its share of displacement that has affected its Black residents, which is the focus of ULI Toronto’s initiative.

“I think Americans, in particular, would understand that Toronto, Ontario, and Canada [overall], [constitute] the terminus of the Underground Railroad and [have] enjoyed a historic misunderstanding of what that means—and perhaps have basked in a halo of progressiveness that isn’t entirely the true story of our history,” says Richard Joy, executive director at ULI Toronto. “It manifests in many ways, including the continual displacement of Black communities throughout our region, a phenomenon that we know little about. We’ve not studied. We’ve not measured. It’s just quietly been part of the structural racism of our city.”

Part of the mission of the team’s project is, first, to aid people in the industry to realize there is an issue, then to help them understand that it is also their concern, according to Kevin Stolarick, who is co-chairing the committee. He said he learned that Black displacement has been taking place in the city for centuries.

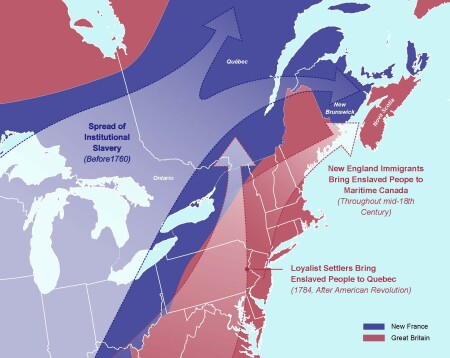

Not only did enslaved people from the United States end up in Canada via the Underground Railroad, but some fought on the side of the British during the American Revolution. Subsequently, some entered Canada as freed men and women. Other Black residents have immigrated in waves that began in the Caribbean and, more recently, in Africa, according to Stolarick.

No matter how they arrived, citizens have fallen victim to Black displacement. ULI Toronto plans to focus upon specific neighborhoods in Toronto such as Weston-Mount Dennis, Jane and Finch, and Little Jamaica among others, according to project manager Abigail Moriah. The group will also study transportation and infrastructure investment and its impact on the Black community.

“The historic displacement of Black communities in Toronto is very much a live issue today,” Joy says, pointing to a transit line project now in development. “It’s happening in real time.”

The project, Eglinton Crosstown Light Rail Transit, will extend roughly 11 miles. There is a risk of Black displacement, as the route runs through Little Jamaica.

ULI Toronto aims to help people in the real estate industry understand how the profession’s standard practices have helped contribute to the problem—and how to find solutions to address the issue.

The work of ULI British Columbia, ULI Houston, ULI Northwest, ULI St. Louis, and ULI Toronto is building awareness of racial injustice in real estate and land use among members and seeking to identify opportunities to engage the real estate industry to enhance community health and reduce wealth disparities. Beyond any specific project deliverable or published report, the legacy of this work may be the meaningful and trusted relationships forged amongst ULI members and partners, and the industry shifts that follow. Learn more about the project at uli.org/partnerships.