This Urban Land opinion piece was written by Mariela Alfonzo, founder of State of Place and a 40 Under 40 winner for 2014.

Ten years ago, I first set foot in Houston to take part in an exercise in placemaking, in some ways before the term had much meaning.

A few weeks before my introduction to the land known for parking lots, strip malls, and barely there sidewalks, I had been attending a ULI conference in Beverly Hills. As a then still-eager PhD student trying to learn “developerese” so I could translate the value of walkability into the “native” real estate language, I was relieved when I happened across three urban brokers from Houston determined to take the place making bull by the horns and make the city more livable and walkable. They had a plan to rank Houston neighborhoods according to their sense of place, with the hope of stirring up competition among them.

As fate would have it, I had been working on a tool to measure the aspects of the built environment that affected walkability—162 of these aspects, in fact. I quickly adapted this research tool to tell a data-driven story about the power of place—and State of Place, my now startup, was hatched. I “graded” 12 neighborhoods in Houston, ranging from Sugarland and Katy to downtown and Montrose, and outlined steps they could take to get a better grade, improve their walkability, and increase their rating in my State of Place Index.

This was ten years ago. The local economy was still (seemingly) going strong. Expansion was still happening outward, not upward. A nice single-family home was still the de facto American dream. Most of the millennials spearheading today’s back-to-the-city movement were still in junior high or high school. Defining great urban design was not enough; marketing neighborhoods on the basis of walkability and sense of place was not enough. If place was going to be part of the equation, I had to “show them the money.”

Today walkability is such a known commodity that it is even the tagline of a major shoe company! The benefits of walkability are now well known. They include lower rates of obesity and associated chronic diseases; reduced emissions of greenhouse gases; improved sustainability and resilience; and even increased happiness. But it is really the economic story that has pushed walkability—and place—into the real estate limelight.

Walkability is no longer something that is merely nice to have or a luxury; it is a key to economic competitiveness. Millennials and seniors are leading the charge. A Transportation for America survey shows that 80 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds want to live in walkable neighborhoods, and an AARP survey found that an average of 60 percent of those over 50 want to live within one mile [0.6 km] of daily goods and services. Walkability even has a role in the innovation and startup economy, with a majority of venture capital going to center cities or walkable suburbs. Even the CEO of Twitter and other tech players are talking about the appeal of an urban campus. Many cities are now going the walkability route after losing bids for large firms to cities in their regions that offered employees a higher quality of life—specifically because of walkability. One example is Oklahoma City.

Walkability is “driving” more than just demand. It is translating into real dollars and cents. In 13 of 15 major U.S. markets, an increase of one point in Walk Score—a proxy for walkability that rates proximity to commercial destinations on a scale of one to 100—translated into home price premiums ranging from $700 to $3,000. An increase of 10 points in Walk Score was associated with an increase of 5 to 8 percent in commercial values. Transit enters the equation as well, with a more than 40 percent premium on property values within walking distance of a transit station.

The value of walkability translates into price resilience, too. After the peak in the housing market in the mid-2000s, residential values in neighborhoods with above-average walkability experienced less than half the decline in value recorded as compared to neighborhoods with below average walkability. In addition, since the recession, prices have risen more sharply in highly walkable central business districts, followed by walkable suburbs, with car-dependent suburbs still struggling to get back to peak prices.

The power of place extends to budgets and economic development. A six-story building in downtown Raleigh, North Carolina, produces 50 times the property tax revenue per acre than an average Walmart store.

In New York City, the city’s Department of Transportation found the following:

- a series of pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure projects translated into significant returns on investment, with protected bike lanes tied to a 49 percent increase in retail sales, compared with 3 percent boroughwide;

- small expansions of pedestrian rights-of-way were tied to a 49 percent reduction in commercial vacancies, compared with 5 percent citywide;

- transformation of an underused parking area translated into a 172 percent increase in retail sales at local businesses over three years; and

- conversion of a curb lane into outdoor seating increasing pedestrian numbers by more than 75 percent and increased sales at bordering businesses by 14 percent.

Nationally, mixed-use downtown development generates ten times the tax revenue per acre than does sprawl development, saves 38 percent on upfront infrastructure costs per unit, and saves 10 percent on ongoing delivery of services.

But while the demand side of the equation is telling one story, the supply side does not match up. Despite the resounding evidence of the multiple benefits of walkability, it is still out of reach for most of the United States. The average Walk Score of U.S. cities with a population over 200,000 is only 47 out of 100—a level categorized as a car-dependent city. Houston’s Walk Score falls just below that at 44. Most cities are facing many barriers to living up to their walkability potential, including dealing with fiscal constraints, acquiring full real estate industry buy-in, gathering political will, addressing community resistance, and measuring real impact.

What does this mean for Houston? How does the city go from the home of giant one-way streets, underused land, and automobile-centric urban design to a dynamic, livable, walkable place? How can it capitalize on the impressive expansion in the number of compact, mixed-use building containing apartments and condos? How can it leverage the significant investments it is making in its beautiful greenways like the Buffalo Bayou? How can it pave a walkable path toward prosperity and resilience? How can it offer the power of place?

I recently found my way back to Houston after nearly an eight-year absence to give a talk at Rice University’s Kinder Institute, precisely addressing how to improve Houston’s sense of place by making the economic case for walkability.

Whereas the original version of the State of Place Index ten years earlier was decidedly before its time, the city’s thinking and our company’s methodology have evolved. In 2012, I cowrote a Brookings study with Chris Leinberger that tied state of place to real estate value. We gathered built environment and real estate data from more than 60 neighborhoods in the Washington, D.C., metro area, a statistically valid sample drawn from over 240 potential neighborhoods along a continuum of walkability from the automobile-dominated exurbs to the highly walkable core.

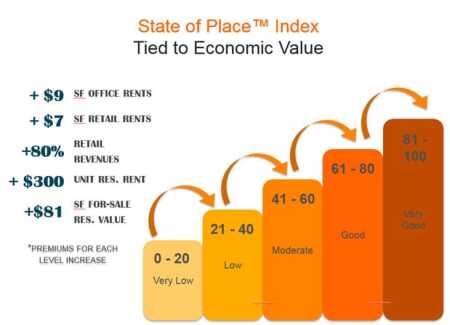

As the State of Place Index increases, so did other real estate values. The index is divided into five levels of walkability – or quality of place – and for each level increase, there was a premium of nearly $9 per square foot in office rents, $7 per square foot in retail rents, an 80 percent increase in retail sales, a $300 per unit increase in residential rents, and more than $81 per square foot in for-sale residential value.

Applying the first official version of the State of Place algorithm—an index that aggregated all 162 built environment features (today there are 286) into a score ranging from 0 to 100, broken down into ten subindices measuring urban design dimensions empirically tied to walkability and quality of place—the study found that as the State of Place Index increased, so did a variety of other real estate values. Specifically, we divided the index into five levels of walkability—or quality of place. We saw that for each level of increase, office rents rose nearly $9 per square foot ($97/sq m), retail rents increased $7 per square foot ($75/sq m), retail sales rose 80 percent, residential rents rose $300 per unit, and for-sale residential values climbed more than $81 per square foot (872/sq m).

Applying these numbers to Houston, in terms of magnitude of impact, if a neighborhood were to move up four levels, it could see about a twofold increase in both retail rents, from today’s average of $14.59 per square foot ($157.05/sq m) to $30.18 per square foot ($324.86/sq m), and office rents, from today’s average of $17.17 per square foot ($184.82/sq m) to $31.81 ($342.40). From an economic development perspective, if Houston were to move up just two State of Place levels, based on its 8.25 percent tax rate, it would double its retail sales from $124 billion to $282 billion, which would translate into an increase from $10.2 billion in tax revenues to $23.3 billion.

Today, rather than just grading places based on their State of Place Index, we integrate the economic tie-in into an urban data analytics platform that weaves a data-driven story of the power of place.

We first classify neighborhoods within a region according to the types of interventions needed in terms of walkability, informing the level and type of investment required across a market area. How much and what kind of investment does a place like Montrose need to reach its full walkability potential as compared to Eastwood or East Downtown (EaDo)?

Next, we set priorities within a neighborhood itself and identify the types of walkability interventions—such as pedestrian amenities, traffic safety, and parks and public spaces—that are most likely to give cities and investors the biggest bang for their buck. If a city has $500,000 to invest in making a neighborhood better, which projects—sidewalk widening, street trees, marked crosswalks—would have the most impact in terms of the desired economic, walkability, and community outcomes?

Finally, we identify specific interventions and/or development projects that would have the biggest impact on the State of Place Index, as well as calculate the predicted return on investment. For instance, if a financier receives several proposals from developers asking for private equity or a city receives several project ideas in response to a request for proposals, we can identify which will have the biggest impact on project revenue or tax revenue, as well which will create the most value in terms of walkability or place itself.

State of Place not only gives cities like Houston the tools to efficiently unlock their untapped value, but also provides the economic rationale for doing so. This helps the city overcome many of the structural barriers to walkability—and I don’t mean just six lane roads.

So if you find yourself exploring Houston during the ULI Spring Meeting, don’t bemoan the blank facades, the decidedly ubiquitous parking lots, and the sprawl. Instead, experience the movement toward place in Midtown, Discovery Green Park downtown, and funky Montrose.

But more important, envision the potential of the Near Northside, a historic, music-focused, bohemian, traditionally Hispanic neighborhood; Harrisburg, an artsy retail street; and EaDo, a burgeoning urban village (or the next midtown). Note their state of place. And in the meantime, I hope to work with Houston to make this next decade the one in which it extols the power of place.

![Western Plaza Improvements [1].jpg](https://cdn-ul.uli.org/dims4/default/15205ec/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1919x1078+0+0/resize/500x281!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fk2-prod-uli.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Fbrightspot%2Fb4%2Ffa%2F5da7da1e442091ea01b5d8724354%2Fwestern-plaza-improvements-1.jpg)