Although they are the embodiment of urban density, tall buildings sometimes get criticized for blocking sunlight, meeting streets in a pedestrian-unfriendly bunkerlike fashion, or filling the sky with blank expanses of glazing. With an increasing reliance on sustainable principles to shape building envelopes in response to climatic conditions, supplemented by creative approaches to mixing uses, incorporating public open spaces, and redeveloping historic high rises, tall buildings have the opportunity to fulfill their potential as defining elements of a city’s character.

The following ten projects—all completed in the past five years—include tall buildings that add vertical greenery to the urban landscape, share the sunlight, generate visual drama with atypical sunshading strategies, embrace new public plazas, and offer changing facades to the surrounding city.

Ron Nyren is a freelance architecture, urban design, and real estate writer based in the San Francisco Bay area.

1. Block 21

Austin, Texas

Built on a former parking lot in downtown Austin, the 37-story Block 21 incorporates the W Austin hotel, residences, shops, offices, and Austin City Limits Live at Moody Theatre. The hot Texas climate informed the building shape and envelope, but the design also took inspiration from the Hopi Indian cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. The south facade incorporates deeply recessed balconies that provide shade during the hot summer months. On the east and west facades, balconies project outward, each one shading its counterpart beneath. Residents with units on the north can slide walls back to create porches.

For the performance venue, the central gathering point on the main floor is another recessed space, designed to feel like the interior of a cave. Parking is tucked underground. The heating, ventilation, and cooling system draws on the city’s district cooling plant, which provides chilled water. Local offices of Andersson-Wise Architects and BOKA Powell designed the complex for local developer Stratus Properties; it was completed in 2012.

2. The Bow

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

The curving form of the Bow, headquarters for two energy companies in downtown Calgary, sheds wind loads more effectively than a rectangular structure would have, allows glazed atriums running the vertical length of the 57-story tower to capture maximal sunlight, and offers the greatest number of perimeter offices with views of the Rocky Mountains. The atriums also help insulate the building.

To encourage employees to interact, three six-story “sky gardens” project into the atriums at the 24th, 42nd, and 54th floors, dividing the building vertically into thirds. In these gardens—the only three places that link express elevators to local elevators—seating areas, meeting rooms, plants, and mature trees create active communal areas. Designed by London-based Foster + Partners and architect of record Zeidler Partnership Architects for developer Matthews Southwest of Mississauga, Ontario, Canada, the Bow connects to Calgary’s system of climate-protected walkways. The second floor, open to the public, houses shops and cafés. The Bow opened in 2013.

3. Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building Renovation

Portland, Oregon

Built in 1974, the 18-story Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building was reaching the end of its useful life, with its building systems failing and its energy use high. Funds made available through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act made an unusual overhaul possible. An energy-efficient and blast-resistant glass curtain wall replaced the uninsulated precast concrete facade, expanding the building envelope to add 31,000 square feet (2,900 sq m) of office space.

On the south and east facades, new vertical shades with horizontal light shelves mitigate heat gain and bounce daylight into the interior. On the west facade, a system of vertical aluminum “reeds” of varying sizes blocks low-angled sunlight. A radiant heating and cooling system replaced the old forced-air system for greater energy efficiency. The roof canopy holds a photovoltaic array and directs stormwater into a basement cistern for use in irrigation, low-flow toilets, and the mechanical system’s cooling tower. Cutler Anderson Architects of Bainbridge Island, Washington, served as design architect, and local firm SERA Architects served as architect of record. The building reopened in 2013.

4. KfW Westarkade

Frankfurt, Germany

Incorporating operable windows into tall buildings is complicated by strong winds. The newest addition to KfW Bankengruppe’s headquarters complex offers a workaround with an aerodynamically shaped form oriented toward the prevailing winds and a two-layer facade. The 14-story building’s double-glazed inner layer holds operable windows for the office spaces, wrapped by a single-glazed layer; the air buffer between the two creates a “pressure ring” around the windows, protecting them from wind.

The outer layer alternates transparent windows in a sawtooth pattern with narrow, colored ventilation flaps that automatically open and close to maintain consistent pressure. The system allows for natural ventilation eight months of the year and provides a high level of insulation. The ventilation flaps face southwest, so they are not visible from the adjacent Palmengarten Park to the northeast, creating a discreet backdrop for the park. Designed by Sauerbruch Hutton of Berlin and completed in 2010, the building curves to present a slim profile to the street. Radiant floor slabs and geothermal heating further lower energy consumption.

5. Mercedes House

New York, New York

Mercedes House is massive, occupying three-quarters of a city block in midtown Manhattan and rising 32 stories at its tallest. Yet its footprint, snaking from one corner of the site to the other in a Z-shape, leaves room for elevated courtyards on either side of the structure, providing breathing space along the side streets. Its massing steps up with each floor, navigating the transition from DeWitt Clinton Park and the shorter buildings along 11th Avenue to taller buildings to the east.

The step-ups also ensure that every unit has a view of the park and the Hudson River to the west. The resulting terraces at each floor incorporate vegetation to reduce the heat island effect and provide views of nature. The base of the building incorporates ground-floor commercial space as well as a Mercedes-Benz showroom and a horse stable for the New York Police Department’s mounted unit. Built on a former parking lot, Mercedes House was designed by the local office of TEN Arquitectos and completed in 2012 for Brooklyn-based Two Trees Management.

6. Metal Shutter Houses

New York, New York

The owner of a two-story building in New York City’s West Chelsea gallery district saw an opportunity to redevelop the site for condominiums, but for much of the day, neighboring high rises cast shadows over the lot. Local firm Shigeru Ban Architects + Dean Maltz Architect designed an 11-story building with each residential unit configured as a duplex so that double-height living rooms and floor-to-ceiling glass windows on the south facade could bring in maximal natural light. The windows retract completely via a motorized system to let in fresh air.

To provide units with privacy, the facade also incorporates perforated metal shutters inspired by the metal security shutters that protect many of the area’s galleries. The screens have their own motorized system, so that they, too, can be raised. The result is a building whose appearance on the street varies as the owner of each of the nine units chooses a different level of openness. The ground floor incorporates a gallery and lobby. The building was completed in 2011 for local developer HEEA Development.

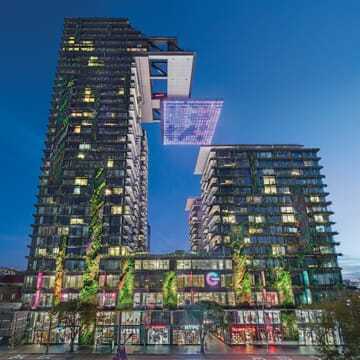

7. One Central Park

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

High rises do not have to block sunlight—they can also redirect it. A 15-acre (6 ha) former brewery site in Sydney’s southern central business district is being redeveloped into a mixed-use residential district that includes a large public park. The first residential component, One Central Park, consists of two towers, 16 and 34 stories tall, above a five-level shopping center. Designed by Ateliers Jean Nouvel of Paris with architect of record PTW Architects of Sydney, the complex includes a cantilevered heliostat that tracks sunlight and reflects it into the adjacent parklands and into the building’s atrium.

At night, Vincennes, France–based artist Yann Kersalé’s light-emitting diode (LED) art installation Sea Mirror plays across the heliostat’s surface, visible from the park. Hydroponic vertical gardens run up and down the facades of the towers, from the second to the 33rd level, helping to shade the interiors. Metal grills protect the plants from strong winds at high altitudes. One Central Park was completed in 2014 for Frasers Property and Sekisui House Australia, both of Sydney.

8. PARKROYAL on Pickering

Singapore

A few blocks from the Singapore River, Hong Lim Park provides the densely built-up city with much-needed green space, taking up an entire block. Across the street, the 16-story office/hotel complex PARKROYAL on Pickering incorporates 161,400 square feet (15,000 sq m) of sky gardens, reflecting pools, waterfalls, planter terraces, and green walls, equivalent to the park’s site area. The E-shaped building’s room blocks rise from an above-ground parking structure, the roof of which is a landscaped terrace sculpted to offer gullies, valleys, and a 980-foot-long (300 m) walking trail. Sky gardens fill in the space between the room blocks and double as sunshades.

Incorporating trees and shrubs, the extensive greenery reduces the heat island effect, provides shade, and cools the air via evaporative transpiration. Rainwater is collected for drip irrigation and supplemented with recycled wastewater from the city. A rooftop photovoltaic cell array powers landscape feature lighting. Designed by local firm WOHA for UOL Group Limited, also local, PARKROYAL on Pickering opened in 2013.

9. Randolph Tower

Chicago, Illinois

A private German social club constructed Chicago’s Gothic Revival–style Steuben Club Building in 1929 to house shops and offices in the 27-story base, reserving the 18-story polygonal tower, along with a ballroom and skylit pool, for members. The Great Depression soon forced the club to sell. By 2001, the terra-cotta facade had deteriorated, and when pieces of it allegedly fell onto the Chicago “L” tracks the city declared the skyscraper a hazard. Detroit-based Village Green bought the structure and brought in local firm Hartshorne Plunkard Architecture and Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates of Northbrook, Illinois, to adapt it for residential use.

About 38,000 terra-cotta tiles were replaced, reused, or repaired in place. Long-missing terra-cotta gargoyles and ornamentation were replaced with new ones based on historic photos and drawings. The ballroom, which had been divided up into office space, was brought back, as were the original pool and its skylight. Completed in 2012, the building was mostly gutted to make way for 312 residential units, with ground-floor retail space and offices on the second floor.

10. Sliced Porosity

Chengdu, China

Sliced Porosity’s five towers range from 29 to 34 stories tall: two office blocks with retail space on the lower levels, one hotel block, and two serviced apartment blocks with retail. They rest on a six-level shopping center base, part of which is underground. The slices that give the complex its porosity—and its name—are a design response to local building codes, which dictate minimum levels of natural light exposure for surrounding buildings.

“Cuts” around the perimeter provide access from surrounding streets to the extensive public plazas on the shopping center’s roof. Three large ponds collect rainwater for reuse and double as skylights, bringing daylight into the shopping center below. Along the perimeter, double-fronted shops offer access to the street and to the shopping center within. Geothermal wells provide heating and cooling for the complex. The Beijing office of Steven Holl Architects, with China Academy of Building Research of Beijing as associate architect, designed Sliced Porosity for CapitaLand China of Shanghai; it was completed in 2012.