From 1971 to 2008, only five states passed legislation enabling land banks; but in the last six years, another eight have done so. As vacancies and blight have plagued parts of the United States still recovering from recession and the mortgage foreclosure crisis, so too has land banking grown. There are now some 120 land banks and land-banking programs, with West Virginia joining the list in 2014.

“Many communities—large and small, urban and rural, from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt—are facing a scale of vacancy and abandonment never seen before,” according to a new Center for Community Progress (CPC) report, Take It to the Bank: How Land Banks Are Strengthening America’s Neighborhoods. (PDF Free to Download; $10 hard copy)

“Problem properties,” says the report, “destabilize neighborhoods, attract crime, create fire and safety hazards, drive down property values, [and] drain local tax dollars,” apart from the human cost.

Related: Tackling the Legacy of Foreclosures in Cook County

Land banks, often through state legislation, are generally granted special powers to overcome many of the legal and financial barriers—clouded titles, years of back taxes, and costly repairs—that might discourage responsible, private investment in neglected properties. Land banks aim to turn these properties from neighborhood liabilities into assets by transferring them to responsible ownership.

State attorneys general have started to recognize that “land banks can be a critical tool to deal with the mortgage foreclosure crisis,” points out CPC vice president Kim Graziani. The attorney generals in New York, Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan have given land banks some foreclosure settlement dollars to acquire problem properties.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneider, for example, awarded competitive grants worth $33 million to land banks for the demolition or rehabilitation of blighted structures. In Illinois, Attorney General Lisa Madigan awarded $70 million for community revitalization and housing counseling, including support for land banking and reuse efforts.

The Evolution of U.S. Land Banking

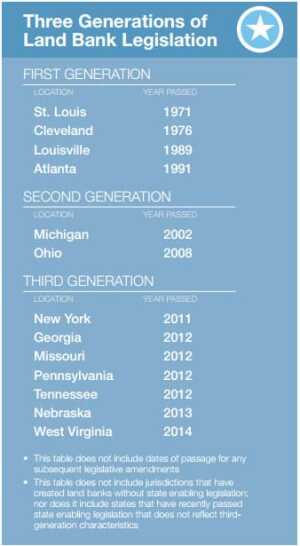

Frank Alexander, a cofounder of CPC and author of Land Banks and Land Banking, has identified three generations of land banks, each generation characterized by more sophisticated reforms and enhanced powers. The first generation (St. Louis, Cleveland, Louisville, and Atlanta) shared a common catalyst—lack of market access to tax-delinquent properties—and all four amassed inventories consisting largely of discarded properties as a result of difficulties in the tax foreclosure process.

The second generation of land banks (Ohio and Michigan) recognized a need to move beyond a custodial role for problem properties to become more proactive partners in their transformation.

Now the third generation of land-bank legislation has drawn upon the lessons of the first two, enabling land banks to operate on a multijurisdictional and regional level, develop self-financing mechanisms, and be linked to the tax foreclosure process.

Part of this third wave, the Cuyahoga County Land Bank in Cleveland, Ohio, founded in 2009, took root in one of the epicenters of the mortgage foreclosure crisis. Ohio’s 22 land banks have benefited from the state’s model legislation, which reformed the tax foreclosure process, granted the power to extinguish all public liens, and created a substantial source of funding.

The Cuyahoga Land Bank focuses on tax foreclosures, but it has become more selective, making strategic decisions on which tax-delinquent properties to acquire. CPC’s report lauds the information management platform and data-driven process the land bank uses to identify and manage eligible property.

Most properties are demolished with what the report indicates is remarkable efficiency, involving eight full-time staff, 90 contractors, and a big dose of technology. In 2013, the land bank tore down 851 properties. In fact, the land bank has developed a demolition guidebook it sells for $1,000 to other practitioners.

The land bank’s funding includes a unique and reliable source known as the Delinquent Tax and Assessment Collection (DTAC). County treasurers are authorized to redirect to land banks the excess penalties and interest generated by collection of delinquent taxes. Cuyahoga County allocates $7 million a year from DTAC to the land bank. This funding stream also provides debt service repayment should Ohio land banks float bonds or borrow.

The Cuyahoga Land Bank has developed a number of creative housing programs to promote affordable housing, homeownership, and preservation. Several of its homeownership programs are targeted at certain populations: owner-occupants, veterans, college graduates, and refugees.

Graziani notes that land banks work in rural areas as well as urban and suburban locales. Three of the seven land banks the CPC report highlights are in rural or semirural counties. Graziani says although problem properties in rural areas may be on a smaller scale and more dispersed than in cities, they “can have a tremendous impact.”

An example of an older, less urban market taking a regional approach is the Macon–Bibb County Land Bank Authority, founded in 1996 and operating in a consolidated city county in Georgia. Though smaller in scale (an inventory of 96 properties, three full-time employees, and revenues of $404,000 in 2013), the land bank has worked to maximize its impact in neighborhood revitalization, affordable housing, and historic preservation. It has done so through a project-driven, neighborhood approach that leverages the talents and resources of nonprofit, private, and government partners. Recognizing it can’t do everything to restore a distressed neighborhood, the land bank concentrates on areas where it can leverage investments by its partners.

Its funding also is project based and comes from multiple sources. Over the years, the Macon Land Bank has secured funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); a community development block grant; HUD’s Neighborhood Stabilization Program; Habitat for Humanity; a local special purpose sales tax; and philanthropies. Local support includes $100,000 each from the city of Macon and Bibb County and additional funds from several city and county agencies.

Job Done or More to Come?

It is hard to say whether the number of land banks will continue to increase in the near term. It may take another economic downturn to spur additional action. A land bank is needed, says Graziani, when local government lacks the capacity, interest, and tools to acquire and dispose of such properties; in other words, she says, communities where the systems of tax collection and enforcement, housing and building code enforcement, and planning and community development are broken and disconnected.