Historic preservation creates new jobs, provides affordable housing, brings diversified economic development, and efficiently maximizes private and public investment. Today, most elected officials and real estate professionals understand the benefits of historic district designation. However, this was not always the case, especially in Denver in the 1980s.

The oil boom of that decade heralded a huge construction boom in downtown office buildings and property values skyrocketed—only to crash with the subsequent oil bust. In the late 1980s, Denver’s Lower Downtown was boarded up and blighted, largely bypassed by the downtown construction boom; it was the city’s skid row. Despite the presence of the Rocky Mountain region’s largest collection of urban historic buildings, between 1981 and 1988 about 20 percent of the buildings in Lower Downtown were demolished, mostly to provide parking for office workers.

In response to the teardowns, a preservation organization called Historic Denver joined a group of business leaders called Downtown Denver Inc. to campaign for a moratorium on demolition in Lower Downtown and for designation of the area as a historic district. The groups were encouraged by Federico Peña, who was elected mayor in 1983 with an ambitious revitalization agenda for the city.

Peña believed that the historic warehouses of Lower Downtown could be used to jump-start the revitalization of the entire downtown, and he made historic district designation a top priority of his administration. When Peña ordered the creation of the Downtown Area Plan, the preservation of Lower Downtown was one of its cornerstones

The Downtown Area Plan was completed in 1987, followed by the Urban Design Plan for Lower Downtown, both envisioning Lower Downtown as a unique urban neighborhood and artistic anchor. The plan for Lower Downtown called for demolition controls in the 23-block historic warehouse neighborhood to protect the area’s critical mass of historic structures.

Despite widespread support for design standards and demolition controls, a majority of property owners in Lower Downtown were against the historic designation. They believed that it took away their property rights and would further erode property values in the already-depressed neighborhood. The crux of the opposition was targeted at the design review and demolition restrictions, which opponents considered draconian and which they believed would decrease the value of their development rights.

Preservationists and city officials argued that Denver had “no point of difference” from other large American cities other than Lower Downtown. “Everything else we’ve built in the last 20 years looks like it could have been built anywhere,” said Jennifer Moulton, city planning director. “We have no identity other than Lower Downtown.” Mayoral aide Tom Gougeon argued that creating a historic district was more important to Denver’s economy than either a convention center or a new airport.

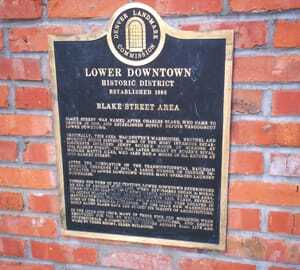

Debate over the proposed historic designation was lengthy and heated, but after four months of protests, petitions, and public hearings, the city council in 1988 passed the Lower Downtown Historic District ordinance, imposing demolition controls and setting design guidelines for new construction and the rehabilitation of existing structures and streetscapes.

Contrary to opponents’ fears, the historic district designations did not stifle investment or reduce property values; they had the opposite effect, spurring private sector investment and spawning development.

Before historic designation, Lower Downtown had a vacancy rate of 40 percent, and 30 percent of the properties had been foreclosed upon. In addition to widespread demolitions, blighted conditions prevailed. After the designation, dozens of historic buildings were renovated to accommodate offices, art galleries, restaurants, bars, housing, and retail uses. Conversion of warehouses into lofts began, and younger residents began moving in. Lower Downtown housing stock grew from 89 units to more than 600 within eight years. The last foreclosed property was sold to a private developer in 1993, and by 1995 the area was home to 55 restaurants and clubs, 30 art galleries, and 650 residences.

In 1995, Coors Field was built for the Colorado Rockies on the northeastern side of the neighborhood, by now known as LoDo. In 1999, the Pepsi Center sports arena opened on the west side. Today, LoDo is home to more than 3,700 housing units and is widely viewed as one of the most popular and successful urban neighborhoods in the Rocky Mountain region.

How did historic district zoning contribute to LoDo’s success? The answer is simple: scarcity and certainty create value in real estate. Historic buildings are a scarce resource; we are not building any more of them. Small businesses and investors were lured to the area by its charm and unique character—and by the knowledge that those attributes would not change. Historic district zoning gave investors assurance that if they spent money rehabilitating a turn-of-the-20th-century building, their investment would not be undermined by the property owner next door tearing down a building to construct a parking lot, put up a billboard, or pursue other insensitive development.

No doubt, Denver’s investment in streetscape improvements and other infrastructure changes, such as removal of a viaduct passing over Lower Downtown, reinforced the private investment and contributed to LoDo’s success. But it is also fair to say that though before historic district designation a building owner could basically do anything he or she wanted with a property in Lower Downtown, there was no investment because there was no certainty about where the neighborhood was going.

Historic district zoning is frequently controversial, but over the years, study after study has shown that it almost always increases property values, commercial revitalization, business investment, and tourism.

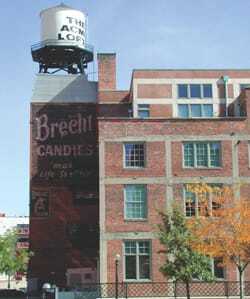

| Left: Acme Lofts, now a residential building, was built in 1909 as the home of BrechtChocolate and Candies. Right: A bronze statue, The Player, greets visitors toCoors Field. The statue is a tribute to Branch Rickey, best known as theBrooklyn Dodgers executive who, in 1945, signed Jackie Robinson for his team. |

A 2011 report focused on Colorado, The Economic Power of Heritage and Place by Clarion Associates, found that 32 new jobs are generated for every $1 million spent on the preservation of historic buildings. Since 1981, historic preservation projects in Colorado have created almost 35,000 jobs and generated $2.5 billion in economic impacts. The report, which examined historic districts in all parts of Colorado, also found that “designation of historic districts does not decrease property values.” In fact, the report found that property values in designated districts appreciated substantially after designation. Property values for all areas examined at least doubled since designation of the district, and within the Fort Collins Old Town Historic District, property values went up nearly 20-fold after designation.

Nationwide more than 40 studies have been conducted on the impact of historic districts on property values. The results vary, as do the length of time covered and diversity of neighborhoods examined, but on the whole, appreciation rates in designated neighborhoods either exceeded or kept pace with those in comparison neighborhoods not designated as historic districts. Historic district designation supports the stability of a neighborhood and helps preserve its uniqueness—an attribute that increases its desirability and differentiates it from other neighborhoods.

The success of LoDo is a story of historic preservation’s ability to generate real estate value and economic growth. Denver is a richer and more dynamic city because visionaries fought to preserve this iconic neighborhood. Moreover, had Denver gone the other way and allowed Lower Downtown to disappear, it would be poorer both in dollars and in spirit.

After all, a city without a past is like a man without a memory.